Introduction: A City on Edge, A Suit on Trial

In the sweltering early days of June 1943, the streets of Los Angeles became a battleground. For nearly a week, from June 3 to June 8, the city was convulsed by a series of violent clashes that would become known as the Zoot Suit Riots. These events were not a spontaneous eruption of chaos but the violent culmination of deeply rooted social, political, and racial dynamics simmering in the crucible of wartime America. The riots pitted mobs of U.S. servicemen—sailors, soldiers, and Marines—along with white civilians and off-duty police officers against the city’s young Mexican American residents, known as pachucos, and other minority youth, including African Americans and Filipino Americans, who dared to wear the flamboyant zoot suit. This report posits that the Zoot Suit Riots were a brutal contest over public space, cultural identity, and the established racial hierarchy, with the zoot suit itself serving as the symbolic flashpoint for a conflict inflamed by a sensationalist press and sanctioned by institutional apathy and complicity. While Los Angeles was the epicenter, it was not an anomaly; it was one of more than a dozen American industrial cities, including Detroit and New York, that experienced significant race-related riots during the summer of 1943, revealing a nationwide crisis of racial animosity exacerbated by the pressures of World War II.

Breakdown of the Zoot Suit’s Signature Features

Drawing on historical sources (such as Wikipedia, Fashion2Fiber, TeachRock, and HistoricGeneva) here’s a detailed description of what constitutes a zoot suit:

1. The Trousers (“Pegged” Pants)

- High waisted: Worn well above the hips, often cinched tight by suspenders.

- Wide-legged: Very full through the thighs and cut wide, giving a ballooning appearance.

- Tight-cuffed bottoms (“pegged”): The widest part is near the thigh, tapering sharply down to a narrow cuff at the ankle. This “pegged” finish is essential to the silhouette. Wikipedia+2Historic Geneva+2

- Such trousers were sometimes pleated and often very long—pooled a bit at the bottom or exaggerated in length for dramatic effect.

2. The Coat (Jacket)

- Long coat: Extends well below the waist—often thigh-length or even to the knees.

- Wide, padded shoulders: Gives a broad, imposing V-shaped silhouette.

- Wide lapels: Large, sometimes sweeping lapels that match the boldness of the suit. Wikipedia+2Historic Geneva+2

- Fitted or cinched at the waist to exaggerate the contrast with the padded shoulders.

- Often fashioned in bold patterns—e.g., pinstripes, bright solid colors, flashy fabrics (bright blue, yellow, purple, sharkskin, etc.). Historic Geneva+1

3. The Hat

- Wide-brimmed felt hat, often a fedora or a pork pie style.

- Frequently color-coordinated with the suit.

- Often featured decorative adornments such as a long feather, worn at a jaunty angle. Wikipedia+2Historic Geneva+2

4. The Watch Chain and Accessories

- A long dangling watch chain (also known as a wallet chain or Albert chain) that usually extending from the waist down toward the knee, sometimes even lower, then back to a pocket. Wikipedia+2Historic Geneva+2

- Often worn with suspenders (braces) instead of a belt, to accommodate and balance the look.

- Accompanied by wide ties or bow ties—sometimes flashy or patterned.

- Two-tone spectator shoes, or other flashy footwear, were commonly part of the ensemble.

Part 1: The Crucible: Social and Political Tensions in Wartime Los Angeles

A City Transformed by War

The Los Angeles of the early 1940s was a city undergoing a profound and destabilizing transformation. As a primary hub for the Pacific theater of World War II, its defense industries boomed and its military installations swelled. This wartime economy triggered an explosive population surge, drawing a diverse mix of people from across the nation—Midwesterners, Southerners, Mexican immigrants, and Black Americans—all in search of economic opportunity. This rapid, unplanned growth severely strained the city’s infrastructure, leading to acute shortages in housing and public transportation. The ensuing competition for limited resources created a fertile ground for friction and hostility between different ethnic and social groups.

Adding to this volatile mix was the massive presence of military personnel. On any given weekend, as many as 50,000 servicemen, many hailing from rural and racially homogeneous parts of the United States, flooded the city’s streets on leave. Unaccustomed to the multiethnic urban landscape of Los Angeles and steeped in the patriotic fervor of the war, these young men brought their own prejudices into a tense and unfamiliar environment, creating a tinderbox of racial and cultural conflict.

A Legacy of Prejudice: Anti-Mexican Sentiment in California

The violence of 1943 was not an aberration but a brutal chapter in a long and grim history of anti-Mexican sentiment in California. Since the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo concluded the Mexican-American War in 1848, persons of Mexican descent, including those whose families had lived in the region for generations, were often viewed by the dominant Anglo society as an inferior class with few rights. This prejudice was institutionalized through discriminatory laws like the Foreign Miners’ Tax, which was designed to eliminate Mexican competition in the gold fields, and was enforced through pervasive violence, including lynchings. Over time, Mexican communities were systematically segregated, pushed into marginalized neighborhoods, or barrios, such as East Los Angeles.

This historical foundation of racism was compounded by the more recent trauma of the Great Depression. During the 1920s and 1930s, a wave of anti-immigrant hysteria led to so-called “repatriation” drives. In this campaign of forced removal, up to 2 million people of Mexican descent were deported; shockingly, an estimated 60 percent of them were U.S. citizens. This mass deportation devastated families and communities, reinforcing a deep-seated mistrust of authorities and cementing the status of Mexican Americans as a foreign and disposable underclass in the eyes of many white Angelenos.

The convergence of this long-standing, systemic racism with the acute pressures of the war created the conditions for the riots. The historical marginalization of the Mexican American community was the chronic condition. The war introduced the acute stressors: a massive influx of newcomers creating resource competition, a climate of hyper-nationalism and xenophobia, and the arrival of a large, transient population of servicemen acting as an accelerant. Primed by patriotic duty and unfamiliar with local culture, these servicemen became the enforcers of a racial hierarchy that felt threatened by the assertive visibility of pachuco youth. The war thus provided both the pretext—patriotism and wartime rationing—and the perpetrators to violently discipline a minority population whose youth were challenging their prescribed social invisibility.

The “Pachuco Menace”: Wartime Hysteria and Juvenile Delinquency

The pervasive wartime atmosphere of fear—of spies, traitors, and enemy agents—was readily projected onto the city’s Mexican American youth. Local newspapers fed this paranoia, at times running columns that explicitly equated the external threat of Japan with the “local threat” posed by these young people. A moral panic over juvenile delinquency, manufactured and amplified by a sensationalist press, became the dominant lens through which the public viewed the pachucos. The zoot suit, their distinctive attire, was transformed from a mere fashion statement into a “badge of delinquency” and a symbol of criminality.

This narrative was bolstered by officials who cloaked their racism in the language of science and law enforcement. In one infamous example, a captain from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department testified before a grand jury that Mexicans possessed a “biological tendency” toward violence and an inbred “desire to kill,” citing their supposed descent from Aztec tribes who practiced human sacrifice. Such statements from authority figures gave an official imprimatur to the racist hysteria, solidifying the image of the zoot-suiter as a dangerous and inherently criminal figure.

Part 2: The Prelude to Violence: The Sleepy Lagoon Murder Case

Death at the Reservoir

The event that crystallized anti-Mexican sentiment and set the stage for the riots was the death of a young man named José Gallardo Díaz. On the night of August 1-2, 1942, Díaz was found unconscious and dying near a reservoir in a rural part of Los Angeles County, a popular gathering spot for local youth nicknamed “Sleepy Lagoon”. His death followed a series of brawls at a nearby party involving rival groups of Mexican American teenagers. The circumstances of his death were ambiguous. An autopsy showed that Díaz was intoxicated and had suffered a skull fracture, but the coroner could not definitively determine the cause of death, which could have resulted from the fights, a fall, or even a car accident. Despite this uncertainty, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and the local press immediately and unequivocally declared it a gang murder.

A Trial by Prejudice (People v. Zamora)

In the wake of Díaz’s death, the LAPD launched a massive dragnet operation, arresting more than 600 young Mexican Americans. These arrests were not based on evidence but on appearance; the police targeted youths who wore zoot suits or had pachuco-style haircuts, effectively criminalizing an entire subculture. From this group, 22 young men, members of the “38th Street gang,” were indicted for murder in what became the largest mass trial in California’s history,

People v. Zamora.

The trial was a flagrant miscarriage of justice, presided over by Judge Charles W. Fricke, who displayed open hostility toward the defendants. The fundamental requirements of due process were systematically violated. Judge Fricke refused to allow the defendants to get haircuts or change out of their zoot suits, forcing them to conform to the jury’s preconceived image of them as “hoodlums”. He denied them the right to sit with or speak to their attorneys during the proceedings and required each defendant to stand whenever his name was mentioned, a practice that created a constant presumption of guilt. In January 1943, despite the lack of any direct evidence connecting them to Díaz’s death, 17 of the defendants were convicted on charges ranging from assault to first-degree murder and sent to San Quentin Prison. The convictions were unanimously overturned by an appellate court in October 1944, which cited the judge’s bias and the lack of evidence, but by then, the damage to the community and the public perception of zoot-suiters was irreversible.

Conviction by Media

The local press played a crucial role in this legal travesty, effectively convicting the defendants in the court of public opinion. Even before Díaz’s death, newspapers like the Hearst-owned Los Angeles Examiner and the Los Angeles Times had been manufacturing a narrative of a Mexican American “crime wave”. Following the arrests, their coverage became a relentless campaign of demonization. Headlines screamed of “MEXICAN GOON SQUADS,” “PACHUCO KILLERS,” and “ZOOT SUIT GANGS,” creating a public hysteria that conflated ethnicity, youth culture, and criminality. The defendants were consistently referred to as “hoodlums” and “baby gangsters,” cementing their guilt in the minds of many Angelenos before the trial had even concluded.

The Sleepy Lagoon case was more than just a flawed trial; it was the institutionalization of the “pachuco menace” stereotype. The police response was not an investigation into a crime but a broad disciplinary action against a demographic defined by its culture. The trial itself, under Judge Fricke’s direction, gave this prejudice the veneer of legal legitimacy, deliberately using the defendants’ appearance to make the zoot suit itself appear criminal within the courtroom. The media then amplified this process, translating the state’s actions into a powerful public narrative of a city under siege. In this way, the Sleepy Lagoon case served as a critical dress rehearsal for the riots. It legally and socially codified the zoot suit as a symbol of deviance, providing the moral justification for the servicemen and civilians who, just months later, would feel entitled to violently attack anyone wearing one.

Part 3: The Fabric of Rebellion: Pachuco Culture and the Zoot Suit

Origins and Aesthetics

The zoot suit was not a creation of the West Coast barrios. Its origins lie in the vibrant African American jazz and ballroom culture of 1930s Harlem, where the style was known as “drapes”. Made popular by iconic performers like Cab Calloway, the suit’s loose fit allowed for the energetic movements of jazz and swing dancing. The fashion migrated westward, where it was adopted by a multiethnic coalition of marginalized youth, including Mexican Americans, African Americans, Filipino Americans, and some working-class white ethnics seeking an alternative to mainstream culture.

The aesthetic was a deliberate performance of excess and style. It consisted of a long, broad-shouldered drape jacket; high-waisted, voluminous trousers that were pegged tightly at the ankle (the “reat pleat”); often a flamboyant hat, such as a pork-pie; and a long, dangling watch chain. It was a look designed to be seen, to take up space, and to command attention.

A Symbol of Defiance

For the young Mexican Americans who called themselves pachucos, the zoot suit was a deeply resonant and complex symbol. It was an act of rebellion against multiple forms of constraint: the conservative, traditional values of their immigrant parents; the intense pressure to assimilate into a hostile Anglo-American society; and the daily reality of socioeconomic marginalization in the barrios. The suit was an assertion of a new, hybrid identity—one that was neither fully Mexican nor accepted as fully American—forged in the unique cultural space of Los Angeles. It signaled pride, masculinity, and a defiant refusal to be invisible. This cultural expression extended beyond clothing to include a unique slang (caló), a confident, swaggering walk, and a social life centered on jazz music, all of which challenged the rigid racial and social segregation of the era.

The act of wearing a zoot suit in downtown Los Angeles was therefore more than a fashion choice; it was a corporeal claim to public space in a city that was geographically and socially segregated. Mexican Americans had long been confined to their barrios, and their presence in “white” public spaces was already seen as a transgression. The zoot suit, with its flamboyant and exaggerated silhouette, made the wearer hyper-visible and impossible to ignore, directly challenging the assimilationist ideal that minorities should be unobtrusive. Servicemen, viewing the city as their patriotic recreation ground, saw these youths not just as unpatriotic but as usurpers of public space. The subsequent violence was, in many ways, a geopolitical struggle for control of the streets. The ritualistic stripping of the suits was a symbolic act of reclaiming that space for the white mainstream, an attempt to forcibly render the pachuco body invisible and push it back into its segregated confines.

An Unpatriotic “Badge of Hoodlumism”

In the hyper-patriotic context of World War II, the zoot suit was easily weaponized against its wearers. In March 1942, the U.S. War Production Board issued regulations restricting the use of fabrics, particularly wool, in civilian clothing to support the war effort. These regulations effectively outlawed the manufacture of the material-heavy zoot suit. To wear one, often obtained from a network of bootleg tailors, was therefore framed as a deliberate and unpatriotic flouting of wartime sacrifice.

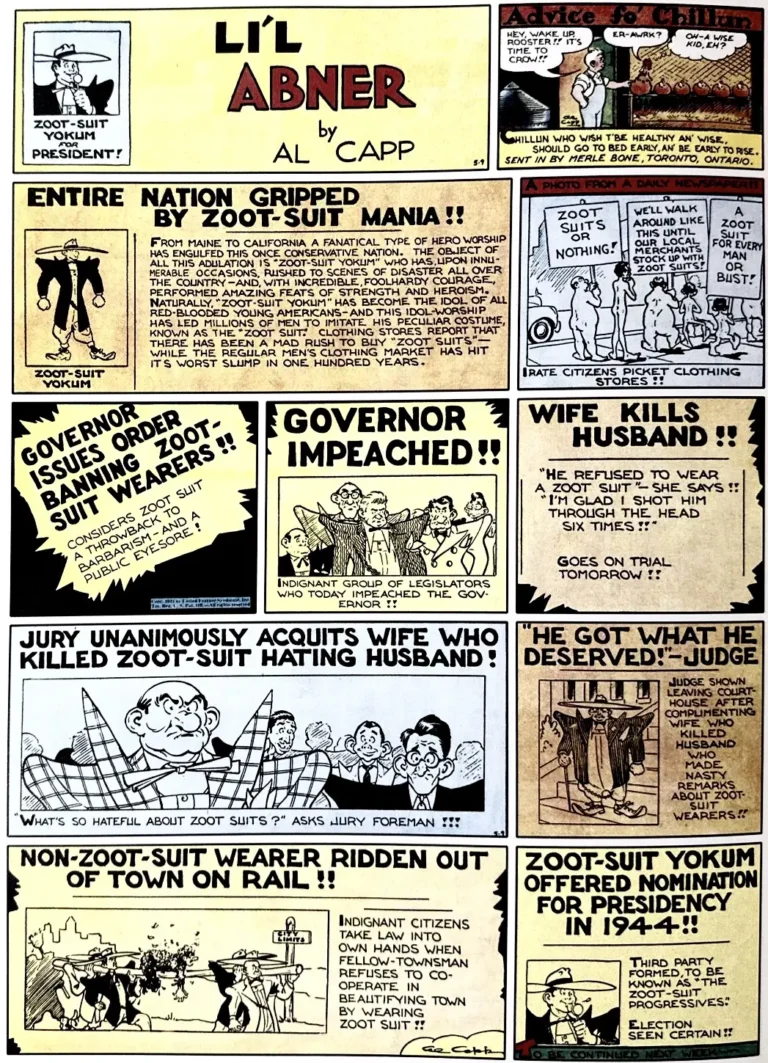

This perception was especially potent among servicemen, who saw the young, non-uniformed zoot-suiters as “draft dodgers,” an accusation often made despite the fact that many pachucos were too young to enlist for military service. This resentment, fused with pre-existing racial prejudice, created an explosive animosity. The media reinforced this stereotype, with nationally syndicated comic strips like Al Capp’s “Li’l Abner” portraying zoot-suiters as disloyal subversives and potential enemy agents, further cementing the suit as a “badge of hoodlumism” in the public imagination.

Part 4: Anatomy of a Riot: A Chronicle of the Violence (June 3–10, 1943)

The Spark (May 30 – June 3)

While tensions had been escalating for months with frequent brawls between servicemen and zoot-suiters, the immediate catalyst for the riots was a series of altercations in late May and early June. On May 30, a U.S. sailor named Joe Dacy Coleman was reportedly beaten and left with a broken jaw by a group of youths. This incident was followed on the night of June 3 by a confrontation on Main Street between eleven sailors and a group of young Mexican Americans. The sailors claimed they were ambushed and beaten; the zoot-suiters insisted the sailors started the fight by insulting them. Regardless of the truth, the sailors’ version of the story became the pretext for organized, large-scale retaliation.

The Escalation of Mob Violence (June 4 – 7)

The violence that followed was not random but methodical and rapidly escalating. On June 4, a mob of around 200 sailors, determined to get revenge, chartered a convoy of approximately 20 taxicabs and drove into the heart of the Mexican American community in East Los Angeles. They began indiscriminately attacking any youth they found wearing a zoot suit, beating them with clubs and other makeshift weapons. The attacks quickly took on a ritualistic quality: victims were stripped of their suits, which were then torn apart and burned in street bonfires.

Over the next few days, the mayhem spread and intensified. Hundreds more sailors, soldiers, and Marines joined the fray, and the mobs were soon swelled by thousands of white civilians who eagerly participated in the violence. Taxi drivers offered free rides to servicemen heading to the riot zones, facilitating the spread of the attacks from downtown to surrounding neighborhoods like Watts and East Los Angeles. The night of June 7 marked the climax of the riots. A mob estimated at over 5,000 servicemen and civilians prowled the streets, engaging in what journalist and witness Carey McWilliams later described as a “mass lynching”.

The Ritual of Humiliation

The violence was characterized by a distinct pattern of public humiliation. Mobs would halt streetcars and buses, board them, and drag out any young Mexican, Black, or Filipino passengers. They stormed movie theaters, demanding that the house lights be turned on so they could hunt for victims in the aisles. The primary objective was often the ritualistic stripping of the zoot suit. Victims were beaten, their clothes were ripped from their bodies, and they were left “bloodied and half-naked on the sidewalk” for all to see. In some instances, servicemen urinated on the tattered clothing, adding a final layer of degradation.

Resistance and Containment (June 8 – 10)

The targeted youths were not entirely passive victims. As the riots wore on, pachuco youths began to organize to defend their communities. They set up ambushes for military vehicles and used decoys to lure small groups of servicemen into traps where they could fight back.

The violence began to subside only on June 8, when senior military command, likely concerned about the escalating chaos and the potential for negative national publicity, finally intervened. They declared the city of Los Angeles off-limits to all military personnel and confined sailors, soldiers, and Marines to their barracks and ships. While this order effectively ended the large-scale rioting, scattered fighting continued for another two days.

TIMELINe of Events

May 30

U.S. sailor Joe Dacy Coleman is beaten, sparking rumors and heightening tensions.

June 3

A group of 11 sailors clashes with Mexican American youths on Main Street. This incident becomes the immediate pretext for retaliation. About 50 sailors leave the Naval Armory seeking revenge, attacking youths in a theater.

June 4

A convoy of over 200 sailors in taxicabs drives into East Los Angeles, systematically attacking zoot-suiters, stripping them, and burning their clothes.

June 5-6

The riots escalate dramatically. Hundreds more servicemen and thousands of white civilians join the mobs. The violence spreads to other neighborhoods, including Watts.

June 7

The riots reach their peak. A mob of over 5,000 servicemen and civilians rampages through downtown Los Angeles, attacking minority youth on streetcars and in theaters.

June 8

Senior military officials declare Los Angeles “out of bounds” for all military personnel, confining them to their barracks. This action effectively quells the large-scale mob violence.

June 9-10

The Los Angeles City Council passes a resolution banning the wearing of zoot suits. Scattered, smaller-scale fighting continues for two more days before subsiding completely.

Part 5: Institutional Complicity: The Role of the LAPD and the Press

“Cleansing Effect”: The Press as Instigator

The Los Angeles press was not a neutral observer of the riots; it was an active participant and instigator. Newspapers lauded the servicemen’s attacks, framing them as a heroic and necessary vigilante action. The press described the violence as having a “cleansing effect” on the city and praised the mobs as a “vengeance squad” doing the job the police had failed to do. This media narrative provided public sanction for the mob violence.

To maintain this skewed perspective, newspapers deliberately suppressed any mention of the white mobs or the indiscriminate nature of their attacks. Instead, they focused their reporting on the arrests of zoot-suiters or highlighted the involvement of female pachucas to reinforce the theme of minority criminality. Headlines consistently and falsely portrayed the zoot-suiters as the aggressors and the servicemen as victims acting in self-defense. The

Los Angeles Times even went so far as to publish a guide on how to “de-zoot” a person, effectively providing instructions for assault.

Abdication of Duty: The LAPD as Enforcers of the Mob

The response of the Los Angeles Police Department was a stark abdication of its duty to protect all citizens, characterized instead by biased enforcement that sided with the rioters. Numerous eyewitness accounts describe LAPD officers standing by and watching as servicemen brutally beat their victims. When confronted, officers would often claim the situation was a matter for the military police and refuse to intervene.

Rather than arresting the perpetrators of the violence, the police systematically arrested the bloodied and beaten Mexican American victims, charging them with offenses such as “disturbing the peace” and “vagrancy”. The situation became so dire that some young men fled to police stations and begged to be arrested, seeing a jail cell as their only safe haven from the mobs roaming the streets. In some cases, the line between police and mob blurred completely, as off-duty officers formed their own “Vengeance Squad” to help “clean up Main Street” from the “loathsome influence of pachuco gangs”.

The press and the LAPD operated in a symbiotic feedback loop that manufactured public consent for racial violence. First, the media created the ideological justification, defining pachucos as a criminal element deserving of punishment through its coverage of the Sleepy Lagoon case and the riots themselves. This narrative then gave the LAPD the public cover to abdicate its duty, implicitly sanctioning the mob’s actions by failing to intervene. The subsequent arrest of the victims, not the attackers, served to ratify the media’s narrative, with the lopsided arrest statistics presented as “proof” that the zoot-suiters were the real criminals. Finally, the press reported on these arrests, completing the cycle and cementing in the public mind the false notion that the riots were a legitimate response to a minority crime wave. This was not simply institutional failure; it was a functioning system of racialized social control.

Part 6: The Aftermath: Official Responses and Immediate Consequences

The Toll of the Riots

While no deaths were officially reported as a direct result of the riots, the human cost was significant. More than 150 people were seriously injured, and hundreds more were subjected to brutal beatings and public humiliation. The starkest evidence of institutional bias can be found in the arrest records, which paint a clear picture of discriminatory policing.

GROUP

NO. ARRESTED

NO. INJURED

Mexican American / Zoot-Suiter

500-600+

150+ (vast majority)

U.S. Servicemen

Very few; temporarily detained by military police

Minimal reported

White Civilians

Virtually none

Minimal reported

As the table illustrates, the victims of the violence were overwhelmingly the ones arrested. While hundreds of Mexican Americans were jailed, very few of the thousands of servicemen and civilians who perpetrated the attacks faced any legal consequences.

The Governor’s Committee and the Tenney Committee

The riots drew national attention and a formal complaint from the Mexican Embassy, prompting California Governor Earl Warren to appoint a citizens’ committee to investigate their causes. The committee’s official report was a surprisingly blunt and clear-eyed assessment. It concluded unequivocally that racism was the central cause of the riots.

Identified Cause

STATUS

Race Prejudice

The report stated that “the existence of race prejudice cannot be ignored” and found it “significant that most of the persons mistreated… were either persons of Mexican descent or Negroes”.

Poor Living Conditions

The committee cited inadequate housing, poor sanitation, and a lack of recreational facilities in Mexican American communities as “breeding places for juvenile delinquency”.

Discriminatory Policing

The report condemned “mass arrests, dragnet raids, and other wholesale classifications of groups of people” as being based on false premises that only aggravated the situation.

Media Incitement

The committee noted that the worst night of rioting occurred in response to “twelve hours’ advance notice in the press,” implicating the media in mobilizing the mobs.

This fact-based assessment stood in sharp contrast to the politically motivated deflections of other officials. Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron dismissed the riots as a simple matter of “juvenile delinquency” versus a “few White extremists”. Meanwhile, the state’s Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, chaired by Senator Jack Tenney, absurdly blamed the violence on a conspiracy by Communist and Axis agents to stir up racial discord.

Legislating Style: The Zoot Suit Ban

The official response from the city of Los Angeles was to blame the victims’ clothing. On June 8, 1943, the Los Angeles City Council passed a resolution that criminalized the wearing of zoot suits on city streets. Councilman Norris Nelson captured the sentiment of the city’s leadership when he declared, “The zoot suit has become a badge of hoodlumism”. While some sources note that a formal ordinance was never signed into law by the mayor, the council’s resolution was widely reported as a ban and served as a powerful symbolic and legal victory for the rioters, validating their violent actions by officially codifying the zoot suit as a public menace.

Part 7: The Enduring Legacy: From Persecution to Political Awakening

An Icon of Resistance

The Zoot Suit Riots, in a profound historical irony, failed to destroy the culture they targeted. Instead, the very act of persecution immortalized it. The violent attempt to strip the pachuco of his identity transformed the zoot suit from a transient youth fashion into an enduring political symbol of Chicano resistance, cultural pride, and defiance. The figure of the

pachuco, once maligned as a delinquent, was reclaimed by subsequent generations as an icon of cultural authenticity and steadfastness in the face of Anglo oppression.

The attempt to violently erase the zoot suit as a cultural marker is precisely what guaranteed its historical immortality. Before the riots, the suit was a subcultural statement. The public, state-sanctioned violence directed at the suit elevated its status, transforming it from a piece of clothing into a martyr’s uniform. Being persecuted for wearing it imbued the zoot suit with a profound political meaning it might not have otherwise retained. The riots, therefore, inadvertently acted as a massive cultural branding campaign. By making the zoot suit the focal point of a major racial conflict, the perpetrators ensured it would be remembered not as a fleeting fad, but as a core symbol of Chicano resilience, making the symbol indestructible by trying to destroy it.

A Catalyst for Activism

The Zoot Suit Riots stand as a foundational event in the development of Chicano political consciousness. The raw, public display of racial injustice served as a radicalizing experience for a generation of Mexican Americans, demonstrating the failure of quiet assimilation and underscoring the urgent need for organized, collective resistance against systemic discrimination. This awakening laid the crucial groundwork for the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, or El Movimiento, of the 1960s and 1970s. The spirit of defiance embodied by the pachucos would echo in the later struggles for labor rights, educational reform, and political empowerment led by activists who drew inspiration from this earlier generation’s stand.

Lessons in American Race Relations

The Zoot Suit Riots offer a powerful and enduring case study on the intersections of race, patriotism, and cultural expression in the United States. When compared to other racial conflicts of that summer, such as the Detroit race riot of 1943, both shared and unique characteristics emerge. The Detroit riot was a more direct, two-way conflict between Black and white residents over jobs and housing, escalating into widespread urban warfare. The Zoot Suit Riots, by contrast, were uniquely characterized by the one-sided targeting of a cultural symbol and the overt complicity of state actors with mob violence.

The events in Los Angeles demonstrate with chilling clarity how a “moral panic,” manufactured by the media and sanctioned by the state, can be used to justify and orchestrate violence against a minority group. The legacy of this injustice continues to resonate. In 2023, eighty years after the violence, the Los Angeles City Council and County Board of Supervisors issued formal apologies for the city’s role in the riots, officially acknowledging the deep-seated racism that fueled them and the profound harm they caused—a modern testament to the riot’s lasting impact on the American conscience.

Sources

General Overviews & Historical Context

- Wikipedia: Zoot Suit Riots

- History.com: The Zoot Suit Riots

- The National WWII Museum: Zoot Suit Riots and Wartime Los Angeles

- Digital History (University of Houston): The Zoot Suit Riots

Cultural Significance & Identity

- PBS American Experience: How the Zoot Suit Got So Much Swag

- PBS American Experience: José Gallardo Díaz and the Zoot Suit

- Unidos For: What were the Zoot Suit Riots?