he Profound Schism: Material Interests, Constitutional Crisis, and the Real Drivers of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was not a singular event stemming solely from resistance to tax burdens, but rather the culmination of a century-long, irreconcilable divergence in political and economic expectations between Great Britain and its North American colonies. The conflict that erupted in 1775 involved profound disputes over sovereignty, territorial expansion, monetary policy, and corporate power, ultimately revealing that the core issue was who possessed the fundamental right to govern the lives and wealth of the colonists. The rallying cry of “no taxation without representation” served as a powerful, unifying ideological shield for a much deeper set of material and constitutional grievances.

I. Introduction: Reframing the Rebellion (Beyond the Tax Rhetoric)

The study of the American Revolution requires moving beyond simplistic narratives. The conflict was not merely about the duty on stamps or tea, but about the imperial government’s sudden, aggressive reassertion of centralized control following a costly global war. This reassertion threatened the economic self-determination and local political structures the colonists had built during decades of relative autonomy.

The Progressive Thesis: Prioritizing Material Interests

Early revisionist historians, particularly those of the Progressive school in the early 20th century, argued that the Revolution was fundamentally driven by material and economic concerns. Scholars such as Charles A. Beard, in his work on the Constitution, and Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr., emphasized that the Founding Fathers’ motivations were deeply rooted in financial self-interest, class conflict, and the pragmatic defense of personal property. Schlesinger’s work The Colonial Merchants and the American Revolution, 1763-1776, specifically detailed how wealthy colonial merchants resisted British policies, such as trade restrictions and new taxes, because those measures jeopardized their profits and established commercial networks.

This historical interpretation posits that revolutionary leaders, many of whom were wealthy landowners, speculators, and businessmen, effectively used the popular language of constitutional rights to mask a pragmatic effort to protect their substantial assets and secure financial stability in the post-war recession. Beard, for instance, argued that the structure of the Constitution itself was shaped by the desire of the elite to protect their investments, particularly federal bonds.

The Ideological Thesis: Prioritizing Republican Liberty

In contrast, the “Ideological School,” championed by historians like Bernard Bailyn and Gordon S. Wood, argued that the conflict was primarily constitutional and philosophical. They contended that the colonists were genuinely motivated by a deep understanding of radical Whig political theory, believing that the actions of Parliament represented a deliberate, calculated “conspiracy” against traditional English liberties.

For these colonists, the struggle was about the erosion of “political liberty,” defined as the capacity to exercise natural rights within limits established by non-arbitrary law, rather than submitting to “the mere will or desire of men in power”. From this perspective, the Revolution was an intense, intellectual defense of inherited rights against a corrupt and autocratic empire, irrespective of the economic costs of resisting imperial policy.

Synthesis: The Fusion of Interest and Ideology

The most robust historical interpretation recognizes the relationship between these two schools is one of profound synergy, not competition. The Revolution was not caused by a single factor, but by an inextricable fusion of elite economic self-interest and popular constitutional belief. The economic policy shifts imposed by Britain created the financial pressures and widespread material discontent necessary for large-scale political action, providing the mercantile and landowning elite with the material motive to lead the rebellion. Simultaneously, the established rhetoric of Whig liberty and constitutional grievance furnished the accessible and unifying language required to mobilize common farmers, artisans, and laborers against the Crown. This dual-pronged motivation—material necessity cloaked in ideological purity—propelled the colonies toward separation.

II. The Imperial Pivot: Debt, Recession, and the End of Salutary Neglect

The critical turning point that necessitated revolutionary action was the massive British fiscal crisis triggered by the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), often referred to in North America as the French and Indian War.

The Financial Burden of War

The Seven Years’ War was enormously expensive, resulting in heavy national debt for Great Britain. Following the Treaty of Paris (1763), Britain gained vast new territories, including Canada and the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. To secure these new possessions and manage the continuing threats of Indigenous resistance, Britain determined it necessary to station a permanent army of approximately 10,000 troops along the North American frontier.

The British government felt completely justified in imposing taxes on the colonists to help cover the costs of these troops, arguing the colonies had benefited directly from the military expenditure that removed the French threat. This shift from distant, lax governance to direct, punitive fiscal policy marked the beginning of colonial resentment and the expansion of imperial authority.

The Assertion of Parliamentary Sovereignty

For much of the 18th century, Britain maintained a policy of “salutary neglect,” allowing the colonies considerable freedom in internal governance, fostering local legislative assemblies, self-reliance, and a sense of political autonomy. After 1763, this hands-off approach was abruptly terminated. Parliament asserted its ultimate, centralized “Parliamentary sovereignty” over the colonies, aiming to enforce trade laws strictly and impose taxes directly to raise revenue.

This aggressive transition was viewed by colonists not as routine policy, but as the emergence of an “autocratic empire in which their traditional liberties were threatened”. The colonists viewed their own elected assemblies as sovereign equivalents to Parliament, believing they alone possessed the legitimate right to levy internal taxes. The conflict was thus fundamentally over the location of sovereignty. The opposition to conceding representation stemmed from the fear among the incumbent landed gentry in Britain that doing so would intensify pressure for democratic reforms in Britain itself, potentially jeopardizing their own established economic and political standing.

The Currency Act of 1764: A Deflationary Shock

A critical, yet often historically understated, material grievance was the Currency Act of 1764. The end of the war brought a postwar recession, compounded by British merchants suddenly demanding immediate payment for colonial debts in British pounds sterling, rather than the colonial paper currency of more questionable value. The Currency Act responded to these demands by prohibiting the colonies from issuing paper currency, mandating a monetary system based on the pound sterling.

The Act was intended to protect British creditors and commerce from depreciated colonial currency. However, its timing and impact delivered a severe deflationary shock to the colonial economy, making it significantly more difficult for colonists to pay existing debts and taxes. This policy was not primarily about revenue generation; it was a systemic financial control imposed externally by the imperial center to favor British commercial interests over colonial debtors and local economic stability. This systemic attack on the financial infrastructure of the colonies, particularly the mercantile class, generated massive, deep-seated resentment that predated the protests against the Stamp Act.

III. Territory, Wealth, and the Speculator’s Revolt

One of the most profound, yet often minimized, material drivers of elite resistance was the conflict over control of the vast western territories. This conflict illuminates the direct intersection of the Founding Fathers’ personal wealth and their revolutionary rhetoric.

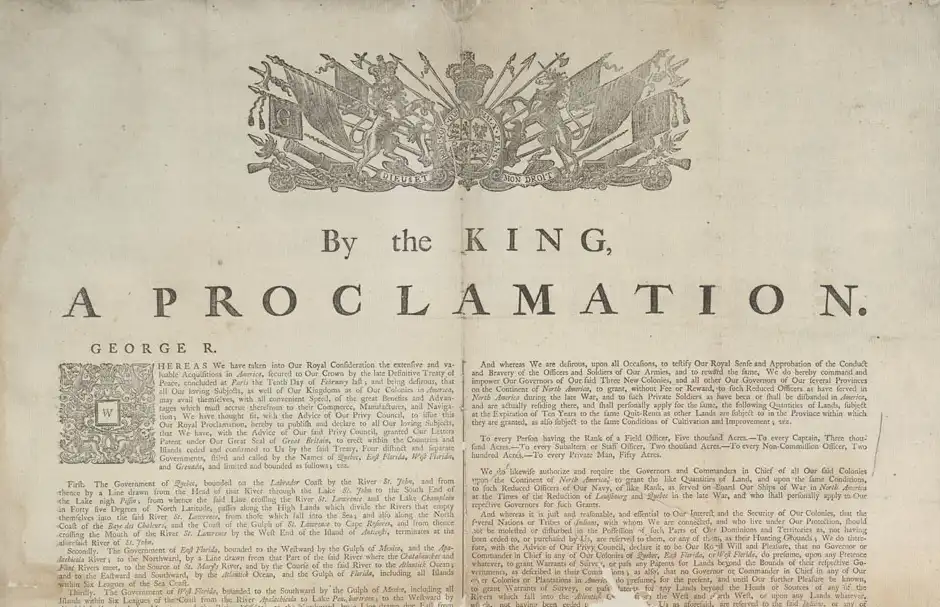

The Proclamation Line of 1763: Confiscation of Vested Capital

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 established a boundary along the Appalachian Mountains, prohibiting Anglo-American settlement beyond that line. The Crown’s rationale was sound from an imperial management perspective: preventing costly Indigenous wars, protecting the valuable western fur trade, and keeping future land speculation firmly under Crown control. Furthermore, the British government worried that unfettered expansion would foster such self-sufficiency among farming families that the colonies would achieve total “economic independence” from the mercantile system.

For the influential colonial elite—wealthy planters and investors—this restriction was an intolerable barrier to wealth creation. They viewed the land acquired in the Seven Years’ War as the central venue for capital investment and future security.

Land Speculation by the Founding Fathers

Key revolutionary leaders were deeply involved in land speculation. George Washington, who had extensive experience as a surveyor, saw the western lands as the future of Virginia and his own financial status. Immediately following the war, Washington founded the Mississippi Land Company (1763), his “most ambitious speculation in western land,” aimed at facilitating rapid settlement in the Ohio River Valley.

Washington and other speculators viewed the Proclamation as a temporary, bureaucratic inconvenience and continued to acquire land rights despite the ban. However, when the Crown followed up on the Proclamation with the Quebec Act of 1774, which extended the borders of the non-representative province of Quebec south to the Ohio River, the Virginia elite saw their material future actively threatened. The British government was not merely delaying expansion; it was attempting to confiscate or fundamentally devalue the vested capital of the most powerful colonial figures. For these leaders, separation became an essential economic defense, guaranteeing them unrestricted access to the lands they believed constituted their economic birthright.

Frontier Violence and Unrestricted Expansion

Colonial discontent was exacerbated by the Crown’s attempts to restore peace after conflicts like Pontiac’s War (1763–1764). Settlers and speculators deeply resented British efforts to enforce treaties and acknowledge Native American land rights. Acts of defiance, such as the Black Boys’ Rebellion in 1765, demonstrated the colonists’ desire to violently secure western territory without the interference of the British military or government. The inability to wage aggressive, unrestrained frontier warfare was, for many western settlers and ambitious eastern elites, a central reason for dissolving their loyalty to a Crown that refused to sanction their expansionist aims.

IV. The Boston Tea Party: An Act of Economic Defense Against Monopoly

The Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773) is often framed purely as a protest against the tax on tea, but a thorough examination reveals it was primarily an act of economic warfare and a defense of colonial mercantile monopolies against an imperial corporate competitor.

The Tea Act of 1773: Corporate Bailout and Monopoly

The Tea Act was not designed to impose a new tax; it retained the small Townshend duty on tea, but its main purpose was to rescue the financially struggling British East India Company (BEIC), which held millions of pounds of unsold surplus tea. To achieve this, Parliament granted the BEIC a government-sanctioned monopoly on tea sales in the colonies.

This act allowed the BEIC to export tea directly to colonial agents (consignees), bypassing colonial middlemen who traditionally purchased tea at auction in London. Crucially, the removal of other required duties meant that the BEIC’s tea could be sold cheaper than legally imported tea and, critically, often cheaper than the vast quantities of smuggled Dutch tea that fueled the lucrative trade networks of the colonial merchant class.

The Threat to Smuggling Operations

The Act directly threatened the business interests of powerful Patriot leaders, many of whom, like John Hancock, made their fortunes smuggling Dutch tea to avoid British duties. Hancock, one of New England’s wealthiest men, and Samuel Adams, were protecting their substantial economic interests by opposing the Tea Act. The direct entry of cheap, monopolistic BEIC tea into the colonial market threatened to bankrupt them and eliminate their control over the highly profitable tea trade.

Strategic Fusion of Motives

The Sons of Liberty, led by figures with significant commercial interests, brilliantly channeled the deep-seated constitutional resentment against taxation into protectionist action. Samuel Adams, a master political agitator, managed to “sell the opposition of British tea to the Patriots on the pretext of the abolishment of human rights by being taxed without representation,” while simultaneously safeguarding the economic stability of his associates and himself.

The destruction of 340 chests of tea was thus more than symbolic. It was a direct, violent action designed to prevent the imperial government from using a monopolistic corporation to restructure the colonial economy and force acceptance of Parliament’s right to tax through economic coercion. The colonists perceived this move as demonstrating Parliament’s terrifying power: if it could grant a monopoly to the BEIC today, it could dismantle colonial private enterprise tomorrow.

V. Legal and Constitutional Erosion: The Assault on English Liberties

The material grievances were amplified by a decade of laws that systematically eroded the colonists’ traditional legal and constitutional protections, confirming the Ideological School’s assertion that a conspiratorial design was underway to establish tyranny.

The Denial of Trial by Jury (Admiralty Courts)

One of the most serious legal grievances was the expansion of jurisdiction for the Vice-Admiralty Courts in the 1760s. These courts handled customs and revenue cases, but they operated under maritime law and crucially did not provide the defendant the right to a trial by local jury.

British officials expanded these courts because colonial juries were notoriously sympathetic to smugglers and often refused to convict those who violated the Navigation Acts. For the colonists, the denial of trial by local jury was an attack on a foundational right guaranteed by English common law. This specific grievance was highlighted in the Declaration of Independence: “For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury”. This procedural erosion was perceived as evidence of judicial despotism and the obstruction of justice.

The Infringement on Private Property (Writs of Assistance)

The Writs of Assistance, which were general search warrants issued to customs officials, also provoked significant legal opposition years before the major tax acts. These writs allowed customs officers to search any property or vessel at any time without needing specific judicial permission or probable cause.

When lawyer James Otis challenged the legality of the writs in 1761, his powerful arguments against arbitrary government intrusion were deemed so pivotal that John Adams later claimed, “then and there the Child Independence was born”. The use of these unlimited warrants represented a direct attack on the sanctity of private property and the right of the subject to be secure in their homes, fundamental protections that the Crown was willing to bypass in its pursuit of revenue enforcement.

The Burden of the Standing Army (Quartering Acts)

The Quartering Acts of 1765 and 1774 required colonial governments to provide housing, food, and supplies for British troops stationed in the colonies, primarily to shift the cost of military presence away from London. Colonists fundamentally resented maintaining a large, permanent army during peacetime, viewing it as a symbol of repression and tyranny. The 1774 Act, enacted as part of the punitive Intolerable Acts following the Boston Tea Party, intensified this resentment by permitting officers to house soldiers in private homes and buildings.

This infringement on personal space and liberty was clearly articulated as an indictment of the King in the Declaration of Independence, which charged him with giving his assent to acts “For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us”.

Erosion of Self-Governance

Beyond the specific laws, the Declaration of Independence catalogs repeated instances where King George III, through his appointed governors, obstructed and undermined colonial legislative authority. The King refused to assent to “Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good,” thereby limiting the efficacy of colonial self-rule. Governors were also instructed to dissolve colonial assemblies, such as the Virginia House of Burgesses, for the simple act of protesting the King’s right to tax the colonies.

These executive and legislative maneuvers confirmed the colonists’ suspicion that their political system was being systematically dismantled, creating a climate where the government was perceived to be pursuing “a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object… to reduce them under absolute Despotism”.

The transition from governance under traditional common law protections (jury trials, specific warrants) to governance by arbitrary executive and military rule (Admiralty Courts, Quartering Acts) constituted a systemic shift. This “tyranny by procedure” demonstrated that the Crown and Parliament were willing to remove the essential safeguards that protected subjects from arbitrary power, fundamentally justifying the colonists’ decision to separate based on a genuine fear of constitutional conspiracy.

The following table summarizes the primary legislative drivers of the conflict, contrasting the stated imperial intent with the material and constitutional impact on the colonies.

Key British Legislation (1763–1774): Imperial Purpose vs. Colonial Grievance

Proclamation of 1763

British Stated Purpose (Imperial View):

To stabilize the frontier, prevent costly Indian wars, and control fur trade.

Colonial/Revisionist Grievance (The “Real Reason”):

Prohibited westward land speculation, jeopardizing the wealth of colonial elites and denying expansionist aims.

Currency Act (1764)

British Stated Purpose (Imperial View):

To protect British creditors by stabilizing colonial currency.

Colonial/Revisionist Grievance (The “Real Reason”):

Restricted colonial economic autonomy, making debt payment (in required sterling) severely difficult during a post-war recession.

Stamp Act (1765)

British Stated Purpose (Imperial View):

To raise revenue for the defense of the colonies, paying for the standing army.

Colonial/Revisionist Grievance (The “Real Reason”):

Established a precedent for internal taxation without colonial consent, directly threatening colonial legislative authority.

Tea Act (1773)

British Stated Purpose (Imperial View):

To rescue the failing British East India Company (BEIC) by granting it a direct monopoly to sell cheap tea.

Colonial/Revisionist Grievance (The “Real Reason”):

Threatened the profits of colonial merchants and smugglers; seen as a tactic to gain colonial consent for the underlying tax and assert corporate control.

Quartering Act (1774)

British Stated Purpose (Imperial View):

To punish Massachusetts and ensure proper housing and supply for troops enforcing the Coercive Acts.

Colonial/Revisionist Grievance (The “Real Reason”):

Direct infringement on personal liberties, forcing colonists to bear the burden of a standing army in peacetime.

Expansion of Admiralty Courts

British Stated Purpose (Imperial View):

To ensure enforcement of trade and revenue laws by bypassing colonial juries.

Colonial/Revisionist Grievance (The “Real Reason”):

Deprived colonists of the fundamental right to trial by jury; indicative of judicial despotism and arbitrary rule.

VI. The Declaration of Independence: An Indictment of Empire and an Assertion of Racial Supremacy

The Declaration of Independence stands as the ultimate bill of particulars against King George III, yet the text reveals that the grievances extended far beyond taxation and included expansionist imperatives rooted in racial prejudice.

Grievances Beyond Taxes

Of the 27 specific charges listed against the King, only one directly addresses the issue of “imposing Taxes on us without our Consent”. The remaining grievances detail a systematic assault on constitutional liberties and local governance, including: obstructing justice, refusing assent to necessary laws, maintaining a standing army without legislative approval, and seeking to subject the colonies to the absolute legislative claims of Parliament. These charges emphasize the colonists’ belief that the King had actively allied with a tyrannical Parliament to strip them of their established rights.

Contextualizing “The Merciless Indian Savages”

The Declaration culminates its list of charges by accusing the King of having “endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions”.

This inflammatory phrase serves two critical purposes. First, it vividly demonstrates the deep-seated prejudices prevalent among white colonial society, particularly in Virginia, where Indigenous peoples were explicitly described as racially barbaric and inherently cruel. Second, and more importantly for the cause of independence, the phrase functioned as a political justification for the rebellion. It framed the Crown’s attempts to pacify the frontier (via the Proclamation Line) and acknowledge Native American land rights as an act of imperial betrayal—a monarch turning “foreign”, savage forces against his own subjects.

The inclusion of this grievance confirms that a core motivation for the rebellion, particularly among the speculative elite and frontier settlers, was the desire for unrestricted territorial expansion and the removal of imperial restraints placed on their aggressive warfare against Indigenous groups. The King’s failure to fully sanction colonial violence and endorse their complete conquest of the West was viewed as a failure of protection, cementing the argument for separation.

The political framing within the Declaration, which accuses the King of inciting violence, cleverly shifts the blame for the bloody frontier conflicts—which were often caused by unchecked colonial encroachment—onto the imperial power. By doing so, the “liberty” championed by the Founders became explicitly exclusionary and territorial, defined as the freedom to wage war and expand without imperial constraint.

VII. Conclusion: Synthesis and the Real Reasons for Separation

The decision by the American colonists to renounce their loyalty to the British Crown was driven by an interconnected series of economic, legal, and territorial challenges that fundamentally redefined the nature of imperial allegiance.

The four critical underlying causes of the colonial rebellion were:

- Fiscal Imposition and Currency Control: The immense debt from the Seven Years’ War forced the Crown to abandon salutary neglect and assert strict fiscal control. The Currency Act of 1764 was a systemic economic shock, favoring British creditors and debtors, and directly hindering colonial economic stability.

- Defense of Vested Capital and Expansionism: The Proclamation Line of 1763 and the Quebec Act directly threatened the primary source of future wealth—western land speculation—for key revolutionary elites, including George Washington. The Crown’s limitation on expansion was viewed as an attack on their capital.

- Protection of Mercantile Interests against Corporate Monopoly: The Boston Tea Party was catalyzed by the Tea Act of 1773, which granted the BEIC a monopoly, posing an existential threat to the lucrative, established trade networks of colonial merchants and smugglers like John Hancock.

- Constitutional Erosion of English Liberties: Parliament and the Crown systematically substituted common law rights (jury trials, protection from general warrants) with arbitrary, executive procedures (Admiralty Courts, Writs of Assistance). This “tyranny by procedure” confirmed the ideological belief that a conspiracy existed to strip the colonists of their traditional constitutional safeguards.

Ultimately, the colonial leaders understood that the British policy shift—from fostering economic growth through benign neglect to aggressively extracting revenue and exerting centralized economic and legal sovereignty—made reconciliation impossible. The “taxation without representation” rhetoric successfully unified the public, but the real reasons for separation lay in the defense of colonial economic autonomy, the protection of elite wealth, and the constitutional imperative to resist what was perceived as an inevitable descent into “absolute Tyranny”.

Historiography & Interpretations

- Reckless Revisionism – The New Criterion

- An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the U.S. – Wikipedia

- The Colonial Merchants and the American Revolution, 1763–1776 – Goodreads

- Where Historians Disagree: The American Revolution – McGraw Hill

- The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution – Wikipedia

- American Revolution – Wikipedia

- 1776 Was More About Representation Than Taxation – NBER

Causes & Early Tensions

- French and Indian War / Seven Years’ War, 1754–63 – Office of the Historian

- Parliamentary Taxation of Colonies – Office of the Historian

- The Stamp Act and the American Colonies, 1763–67 – UK Parliament

- Proclamation of 1763 – Gilder Lehrman Institute

- Shift from Salutary Neglect to Parliamentary Sovereignty – Gauth

- Currency Act of 1764 – American Battlefield Trust

- Timeline: 1764–1765 – Library of Congress

- Proclamation Line of 1763 – George Washington’s Mount Vernon

- Proclamation Line of 1763, Quebec Act of 1774 – Office of the Historian

- Frontier Rebels – Museum of the American Revolution

Boston Tea Party & Tax Protests

- The Tea Act (1773) – Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum

- The Boston Tea Party – American Battlefield Trust

- Boston Tea Party Cause – Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum

- Tea Act of 1773 – EBSCO

- John Hancock and the Boston Tea Party – Raab Collection

Declaration of Independence

- The Declaration’s Grievances Against the King – Constitution Center

- Adams Papers Digital Edition – Massachusetts Historical Society

- Declaration of Independence: A Transcription – National Archives

- Grievances of the U.S. Declaration of Independence – Wikipedia

- Annotated Grievances – Gilder Lehrman Institute

- Indictment Against King George III (Lesson Plan) – USHistory.org

- The Declaration of Independence: What Were They Thinking? – NPS

Laws, Courts & Rights

- Admiralty and Maritime Jurisdiction – U.S. Constitution Annotated

- Courts of Admiralty in Colonial America (1634–1776) – UMD Law

- James Otis Against Writs of Assistance (1761) – Constitution Center

- Writs of Assistance: Definition & Purpose – Study.com

- Quartering Act – EBSCO

- Quartering Acts – Wikipedia

- Stamp Act Crisis – EBSCO

Land, Expansion & Native Americans

- George Washington, Land Surveyor – Virginia Museum of History

- George Washington and the West – Mount Vernon

- Mississippi Land Company – Mount Vernon

- Free to Speculate: Colonial Land – Richmond Fed

- Native Americans – Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

- A “Merciless” Reminder on July 4 – Native American International Caucus