Executive Summary

The Strijdom Square massacre, a racially motivated shooting spree carried out by white supremacist Barend Hendrik Strydom on November 15, 1988, stands as a stark and tragic event in the twilight of apartheid South Africa. This report provides a detailed examination of the attack, its perpetrator, the complex political and legal processes that followed, and the enduring legacy of unrepentant hate that challenges the nation’s efforts at reconciliation. The analysis reveals a series of interconnected events that were shaped by the country’s turbulent transition. Barend Strydom, a radicalized individual with a history of violence and a profound belief in white supremacy, executed a premeditated attack in a symbolic location, killing eight people and injuring sixteen. His subsequent release from prison was not a simple act of forgiveness but a politically contentious process involving two distinct stages: his initial release as a political prisoner by President F.W. de Klerk in 1992 and his later, though ultimately withdrawn, application for amnesty from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The report concludes that while South Africa’s transitional justice model provided a framework for restorative justice, the case of Strydom demonstrates its philosophical and practical limitations when a perpetrator remains wholly unrepentant.

TIMELINE OF KEY EVENTS

15 November 1988

Barend Strydom carries out the Strijdom Square massacre in Pretoria, killing 8 people and injuring 16.

25 May 1989

Strydom is convicted and sentenced to death for the murders and 30 years for attempted murder.

1990

The South African government declares a moratorium on capital punishment, halting Strydom’s execution.

29 September 1992

Strydom is released from prison by President F.W. de Klerk as part of an agreement to free political prisoners.

1993

Strydom is indemnified and released after serving just four years of his commuted life sentence.

1994

He is granted amnesty by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on the grounds that his attack was politically motivated.

14 March 1997

Strydom’s lawyer states he is seeking amnesty from the TRC to be protected from civil claims by victims’ families.

29 April 1998

Strydom withdraws his amnesty application, claiming the government is using the process to “humiliate and belittle the Boer nation”.

2003

Strydom is investigated for his support of right-wing extremist causes after publicly supporting another shooter, De Wet Kritzinger.

2008

Strydom testifies at the Boeremag trial, stating that he still believes black people are not human.

15 November 2018

The 30th anniversary of the attack is commemorated with a ceremony where the victims’ names are read aloud and a commemorative plaque is dedicated.

1. Historical and Political Context: The Brink of a New Dawn (1988)

The Strijdom Square massacre occurred at a pivotal and volatile moment in South African history. By the late 1980s, the decades-long system of apartheid was in a state of terminal decline, a reality that created a complex political environment of both hope and violent desperation. The country was under a nationwide state of emergency, a measure first declared in 1985 and extended in 1988, which had failed to quell the widespread civil unrest and had instead deepened the country’s ungovernability. The apartheid government was also facing immense pressure from multiple fronts. Internally, the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) was gaining strength, and tentative, often secret, talks were beginning between the government and key anti-apartheid figures like Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) in exile. Internationally, economic and cultural sanctions, spearheaded by grassroots movements and formalized by legislation like the United States’ Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, were crippling the South African economy.

For a white supremacist like Barend Strydom, these developments were not signs of a necessary transition but an existential threat to his way of life and ideology. The emerging possibility of a non-racial, democratic South Africa represented the complete collapse of the social order he believed was divinely ordained. His attack was not a random act of madness but a calculated and premeditated act of terror. He chose to carry it out in Strijdom Square, a location named in honor of former prime minister J.G. Strijdom, a figure notorious for his support of racial segregation and the baaskap (boss-ship) policy. The square featured a large statue of Strijdom’s head, which made it a potent symbol of white minority rule and a fitting stage for a final, violent protest against the new reality. The timing of the attack—coming just as the apartheid state was revealing its profound weakness and the prospect of a negotiated settlement was becoming more apparent—underscores its nature as a desperate act of resistance against an inevitable political transformation.

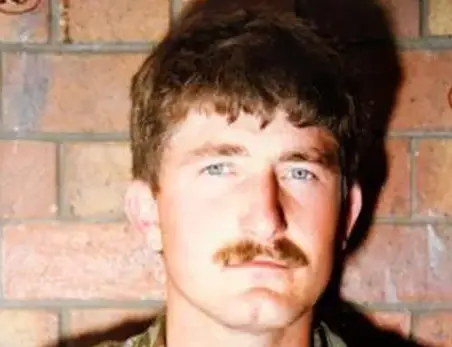

2. The Perpetrator: Barend Hendrik Strydom, An Agent of Ideological Hate

Barend Hendrik Strydom, the perpetrator of the massacre, was a product of a deeply entrenched white supremacist worldview, a fact that distinguishes him from the renowned South African scientist Dr. Barend Wilhelm (Ben) Strydom, a microbiologist who passed away in 2018. The murderer’s life was shaped by early tragedy and ideological indoctrination. Born in 1965, he was an infant when his mother committed suicide, an event he was told was a revolver accident until after the shooting. His extreme views were actively encouraged by his father, and he had been a member of extremist right-wing organizations since the age of 16. His dehumanizing perspective was a central feature of his ideology; he openly stated that he “viewed black people as animals”. This mindset was not just theoretical; it manifested in prior violent acts, including his dismissal from the South African Police after he photographed himself with a knife and the severed head of a black motorist at an accident scene.

After his arrest, Strydom attempted to frame his individual act of violence as a coordinated political action. He claimed to be the head of a group called the Wit Wolwe (White Wolves), stating that the organization would take up the battle against the ANC. While other sources claimed the group was real and dated back to the 1970s, it was largely dismissed by investigators as a “fictitious organization invented by Strydom”. This self-proclaimed affiliation highlights his desire for his actions to be viewed not as the crime of a lone individual but as a political statement on behalf of a wider movement. His psychological profile, as testified by experts during his trial, confirmed that he was “eccentric but not insane” and knew exactly what he was doing. This testimony, combined with his prior acts and his “practice run” shooting of a black woman a week before the massacre , demonstrates that his violence was a premeditated and calculated expression of his deep-seated white supremacist ideology, not an act of spontaneous mental instability.

3. The Massacre: A Detailed Account of the Strijdom Square Atrocity

On the afternoon of November 15, 1988, Barend Strydom executed his calculated attack in the heart of Pretoria. At approximately 3 p.m., the 23-year-old, dressed in camouflage and armed with a 9mm Vektor pistol, two magazines, and 200 loose bullets, walked into Strijdom Square. His motive was clear: to kill any black person he encountered and to “start a race war”. He began his shooting spree by opening fire at random, smiling throughout the event as he walked through the square and nearby streets. His killing spree left a trail of chaos and death, as he continued shooting people across several blocks.

The human toll of the attack was severe. Eight people were killed and 16 were injured in the main attack. Seven of the victims who died were black, and one was Indian. One of the wounded victims was paralyzed from the waist down, a permanent reminder of the violence. The simple casualty count is further complicated by the fact that the woman he killed in a black squatter camp a week earlier was part of what he called a “practice run” for the main event. Accounting for this prior murder brings the total number of people killed to nine. The massacre was brought to an end by the courageous intervention of a black taxi driver named Simon Mukondoleli. As Strydom was reloading his gun inside a nearby building, Mukondoleli followed him, tapped him on the shoulder, and disarmed him at gunpoint. Strydom surrendered, stating, “You’ve got me”. The report must also acknowledge the tragic footnote to this event: Mukondoleli was later killed in a separate attack in 1991, an event that some believe may have been related to his work as a private investigator.

4. The Victims: Honoring the Unnamed and the Bereaved

The immense human cost of the Strijdom Square massacre is quantified by the number of casualties, but the true impact lies in the individual lives lost and irrevocably changed. In the main attack, eight people were killed, and sixteen were wounded. The racial demographics of the deceased underscore the targeted nature of the violence: seven victims were black, and one was Indian. A week earlier, Strydom had also killed a black woman in a separate, but related, incident.

While the number of casualties is clearly documented, the challenge of finding a complete list of the victims’ names in public records is a significant aspect of the case’s legacy. The comprehensive database of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) does not explicitly list the names of the Strijdom Square victims, although it does contain detailed records of many other acts of political violence. This gap in the formal documentation stands in contrast to the persistent efforts of affected communities to ensure the victims are not forgotten. A powerful act of remembrance occurred on the 30th anniversary of the attack on November 15, 2018, when a ceremony was held in the square. During the event, a commemorative plaque was dedicated, and the names of the victims were read aloud. One of the victims, Satat Carrim, was publicly remembered when his son recounted the day his father was shot. This act of public commemoration, in the very place where the atrocity occurred, reveals an important dynamic in South Africa’s post-apartheid experience. While official legal and historical processes may have their limitations in capturing the full human dimension of suffering, the act of remembering and honoring the dead becomes a crucial, community-led component of national healing.

5. Legal Proceedings and the Road to Release

Barend Strydom’s journey through the South African justice system was as contentious as the political landscape it inhabited. During his trial, Strydom remained unapologetic, laughing and joking in court, and even telling the police he regretted not killing more people. He claimed his actions were the will of God and justified the killing of an elderly woman by stating, “She threatened my existence because she was black and because she was alive”. Despite his claim of self-defense, psychiatric experts testified that he was “eccentric but not insane”. On May 25, 1989, he was convicted of murder and attempted murder and sentenced to death by hanging, with an additional 30-year sentence for attempted murder. The presiding judge noted that his actions were “worse than those of terrorists” because he laughed while shooting his victims, unlike those who leave bombs.

The user’s assertion that the African National Congress (ANC) released Strydom as an act of good faith is a common but significant misconception. The sources clarify that the decision to release him was made by President F.W. de Klerk’s government. On September 29, 1992, Strydom was released as one of 150 political prisoners. The ANC actually condemned the release. This release was not an act of benevolence but a key component of a complex and highly politicized negotiation process. The de Klerk government’s goal was to reduce white South African criticism of its concessions to the ANC by showing a political balance. The release of a prominent white supremacist like Strydom was deliberately paired with the release of black liberation fighters like Robert McBride, who had killed whites in the Magoo’s Bar bombing. This calculated trade-off reveals the strategic, often difficult, nature of the negotiations to end apartheid.

6. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC): A Model of Restorative Justice

The establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) represented a monumental shift in South Africa’s approach to post-conflict justice. The Commission was tasked with investigating gross human rights violations committed between 1960 and 1994, and it was championed by figures such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu. At its core, the TRC was founded on the principles of restorative justice, which, in contrast to a retributive model that seeks punishment, aimed to heal the rifts in a broken society by restoring relationships and community. This philosophy was deeply rooted in the African concept of Ubuntu, which translates to “I am because we are” and emphasizes the interconnectedness of all humanity. Tutu believed that this approach was the only way for the nation to heal, as it required both victims and perpetrators to find a path toward forgiveness and reconciliation through truth-telling.

The TRC’s mechanism for achieving this was conditional amnesty. Perpetrators who committed politically motivated crimes were offered immunity from prosecution if they provided a full and truthful disclosure of their actions. In this context, Strydom’s case presents a profound paradox. While some sources state that he was granted amnesty by the TRC in 1994 , public records from the time show a more complex reality. Strydom did apply for amnesty, doing so to avoid civil claims from his victims’ families and to lift his parole conditions. However, he withdrew his application in April 1998, stating that he believed a general amnesty was the only solution and that the government was using the process to “humiliate and belittle the Boer nation”. This action is a powerful demonstration of the limitations of the TRC’s restorative model. The Commission could provide the framework for truth and forgiveness, but it could not force a perpetrator to seek genuine reconciliation or show remorse. In the end, Strydom rejected the very process designed to offer him a path back into society.

7. An Unrepentant Soul: Life and Legacy After Prison

The user’s observation that Barend Strydom maintained his racist views after his release is entirely accurate and is one of the most troubling aspects of his legacy. His life after prison served as a direct challenge to the idea that the country could simply move on. Immediately following his release, Strydom demonstrated his continued adherence to white supremacist ideology, stating that he would “do it again ‘if necessary’”. This was not merely an isolated remark. His actions in the years that followed provided compelling evidence of his unchanged beliefs.

In 2003, he was investigated for his support of other right-wing extremist causes. This was prompted by his public support for De Wet Kritzinger, a white supremacist who had shot and killed three black people on a bus in Pretoria in 2000. After Kritzinger was sentenced, Strydom publicly read a statement of support, calling him a “prisoner of war” and reinforcing his own identity within a continued racial struggle. The most definitive proof of his unrepentant nature came in 2008, when he testified in the Boeremag trial to defend another extremist. During his testimony, under oath, he unequivocally stated that he “still believed black people were not human”. This chilling admission, made two decades after his massacre, perfectly encapsulated the philosophical challenge his case posed to the TRC’s model. His journey—from a convicted killer sentenced to death to a free man who continued to espouse the same hate that motivated his crime—exposes the profound complexities of transitional justice. It shows that while a legal and political process can grant forgiveness, it cannot necessarily compel a change of heart, leaving a painful and enduring question about the true meaning of national reconciliation.

General Reference Sources

South African History Resources

- Barend Strydom kills 8 People in Pretoria | South African History Online

- A State of Emergency – South African History Archive

- The Mass Democratic Movement, February 1988 – January 1990

- The End of Apartheid – Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations – Office of the Historian

Truth and Reconciliation Commission Documents

- 29 Apr 98 – BAREND STRYDOM WITHDRAWS AMNESTY APPLICATION – SAPA

- 14 Mar 97 – ‘IT WAS WAR’, SAYS STRYDOM IN AMNESTY BID – SAPA

- strydom, a – Truth Commission

- Export Victims for Letter: M

- Download Complete TRC Victims List (6.4Mb)

Academic and Educational Resources

- Examining South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission – The Colleges of Law

- Restorative Justice and the South African Truth and Reconciliation Process – Pure

- The Philosophy of Life Based on Desmond Tutu: Ubuntu, Compassion, and Social Justice

- Four Lessons From Desmond Tutu’s Life and Legacy | United States Institute of Peace