Overview

“Salt of the Earth” holds a unique distinction in American cinema: it remains the only feature film in U.S. history to be systematically blacklisted through coordinated government, industry, and union suppression. The 1954 film, directed by Herbert J. Biberman and produced by Paul Jarrico—both already blacklisted during the McCarthy era—faced unprecedented obstacles at every stage of production. From congressional denunciation and FBI surveillance to violent vigilante attacks and the deportation of its lead actress, the film’s creation became an act of defiance that cost its makers their careers, livelihoods, and in some cases, their freedom. Yet against impossible odds, the film was completed and would eventually be recognized by the Library of Congress as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

The filmmakers who refused to stay silent

All principal creative personnel on “Salt of the Earth” were blacklisted before production began, making this one of the first fully independent films created entirely outside the Hollywood studio system as a direct response to political persecution.

Herbert J. Biberman directed the film after serving six months in federal prison at Texarkana, Texas. As one of the Hollywood Ten, Biberman had refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in October 1947 on First Amendment grounds. He was convicted of contempt of Congress on November 24, 1947, sentenced in 1950, and immediately expelled from the Directors Guild of America (his membership wasn’t restored until 1997, 26 years after his death). His wife, Oscar-winner Gale Sondergaard, was also blacklisted and found virtually no work until shortly before Biberman’s death from bone cancer in 1971. After “Salt of the Earth,” Biberman directed only one more film—the poorly received “Slaves” (1969).

Paul Jarrico produced the film after being fired from RKO Studios in April 1951, literally stopped at the studio gates the day after he was named before HUAC. “One day my name was in the papers,” Jarrico later recalled. “The next day, when I showed up for work, they stopped me at the studio gates.” He had been betrayed by his close friend and screenwriting partner Richard Collins, who named him on April 12, 1951. When Jarrico testified the next day and invoked the Fifth Amendment, he lost his $2,000-per-week job at Columbia Pictures immediately. The U.S. government confiscated his passport, and he later lost a lawsuit against Howard Hughes to restore his screen credit for “The Las Vegas Story” (1952) under a morals clause for “placing himself in public obloquy.” He would spend nearly 20 years in European exile before returning to the U.S. in 1975. On October 28, 1997, Jarrico died in a car crash on the Pacific Coast Highway—driving home from a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of HUAC’s first Hollywood hearings.

Michael Wilson wrote the screenplay after being fired by 20th Century-Fox production chief Darryl Zanuck in June 1951, before he even testified. Wilson had just won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for “A Place in the Sun” (1952), but that success meant nothing. After invoking the Fifth Amendment before HUAC on September 20, 1951, he was blacklisted for 13 years. He wrote major films uncredited or under pseudonyms, including “The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957)—credit went to Pierre Boulle, who couldn’t speak English—and “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962). Wilson’s Oscar for “River Kwai” was only restored posthumously in 1984, six years after his death from a heart attack at age 63. His “Lawrence of Arabia” credit wasn’t restored until 1995, 17 years after his death. The U.S. government revoked his family’s passports so they couldn’t return from European exile.

Will Geer, who played the sheriff, refused to become an informer and was summoned before HUAC in the early 1950s. Before the blacklist, he appeared in “Winchester ’73” (1950), “Broken Arrow” (1950), and “Bright Victory” (1951). “Salt of the Earth” was his last film until Otto Preminger broke the blacklist by casting him in “Advise & Consent” (1962). He eventually found television success as Grandpa Walton on “The Waltons” (1972-1978), winning an Emmy in 1975.

These blacklisted filmmakers formed the Independent Productions Corporation (IPC) in 1951 with $10,000 from Simon Lazarus and $25,000 from sympathetic businessmen. Having already been punished, as Jarrico put it, “Salt of the Earth was our chance to really say something in film, because we had already been punished.” They would make the most subversive film they could imagine.

Congressional denunciation before a single frame was shot

The attacks began before principal photography even started. On February 9, 1953, The Hollywood Reporter published an inflammatory piece warning that “H’wood Reds are shooting a feature-length anti-American racial issue propaganda movie at Silver City, NM.” According to Jarrico, the article noted that Screen Actors Guild president Ronald Reagan “immediately alerted FBI, State Department, HUAC, and CIA.”

On February 24, 1953, California Republican Congressman Donald L. Jackson took to the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives to denounce a film that was still being shot. “I shall do everything in my power to prevent the showing of this Communist-made film in the theaters of America,” Jackson proclaimed. He called it “a new weapon for Russia” and claimed it was “deliberately designed to inflame racial hatreds and to depict the United States of America as the enemy of all colored peoples.” Jackson warned that if shown in “Latin-America, Asia and India, it will do incalculable harm, not only to the United States but to the cause of freedom everywhere.”

The timing was no coincidence. Just one day later, on February 25, 1953, the Immigration and Naturalization Service would strike.

The deportation that nearly destroyed the film

February 25, 1953: INS agents arrived on the set in Silver City, New Mexico, and arrested Rosaura Revueltas, the Mexican actress playing the lead role of Esperanza Quintero. The official charge was an alleged passport violation—her passport had not been properly stamped upon entry to the United States, a technical error the government later admitted was their own fault.

Revueltas was driven 150 miles to El Paso, Texas, held under armed guard in a hotel room, and repeatedly interrogated about whether she was a Communist. “She said she didn’t know, that she was just working on the picture, and she hummed,” according to one account. Released on March 6, 1953—nine days later—she was ordered to return to Mexico and permanently banned from working in American films.

The deportation came approximately nine days before the scheduled completion of principal photography, forcing the filmmakers to improvise desperately. They used a stand-in filmed from behind to complete necessary scenes. Months later, crew members secretly traveled to Mexico to film final close-ups of Revueltas near her home outside Mexico City, disguising the footage as “audition footage of an aspiring actress.” Her crucial voice-over narration—Esperanza’s inner thoughts form the film’s narrative structure—had to be recorded in a dismantled Mexican sound studio and smuggled across the border like contraband.

Revueltas had known the risks. Before making the film, she was warned by multiple people, including her wealthy German husband, who told her: “You are now beginning your career and you have only made three films, but they have been prize winners. If you make this film you won’t make anything else.” Her response: “It doesn’t matter to me. I’ll make it even if I don’t work again, because I knew what was going to happen.”

She was right. Revueltas was blacklisted in both the United States and Mexico for 22 years. She moved to East Germany (1957-1960) to work with Bertolt Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble and performed in Cuba in 1961, but didn’t appear in another film until 1976. She never regretted her decision. “I never cared about making the film to act as the lead actress, because I knew that with that film I would lose my career,” she told Radio UNAM. “If the circumstances were to arise again, I would do the same.” Despite winning Best Actress at the 1954 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia, she never made another American film. She died in Cuernavaca, Mexico, on April 30, 1996, at age 85.

Film historians note that “the film is marred aesthetically by these outside pressures, since the tension and violence that marked the final shooting days and Revueltas’s deportation necessitated the inclusion of some poor sound footage and mismatched edits.”

Violence, bullets, and burning union halls

The deportation was only one element of the violence that plagued production during those final weeks of February and March 1953.

On March 3, 1953, at 1:30 a.m., up to five bullets were fired into the parked car of Clinton Jencks, the real-life union organizer who played a character based on himself in the film. Later that same day, vigilantes broke up filming in front of the union hall in Silver City. A mob knocked over camera equipment, punched cast and crew members, and left Jencks with a black eye. The crew received an ultimatum: leave by noon the next day “or go out in black boxes.”

On March 7, 1953, the Mine-Mill union hall was burned to the ground, along with the home of Floyd Bostick, who played Jenkins in the film. Throughout production, rifle shots were fired at the set, crew members’ cars were attacked, and a small airplane buzzed overhead constantly to disrupt sound recording. “We’ll make this picture again sometime,” producer Jarrico joked bitterly. “And next time we’ll say, ‘You’ve seen this great picture. Now hear it.’”

State police had to be called in to patrol the streets so filming could be completed. Silver City, population 7,000, became an armed camp. The local newspaper, the Silver City Daily Press, published inflammatory articles suggesting that citizens should forcibly remove the “communists.” Local merchants refused to do business with crew members, and hotels wouldn’t house them.

The production faced these attacks despite—or rather because of—its attempt to tell the story of a real labor struggle: the 15-month Empire Zinc strike of 1950-1952, the longest strike in New Mexico history. The strike involved 92 union members (80 Hispanic, 12 Anglo) fighting discriminatory labor practices at Empire Zinc Company in Hanover, New Mexico. Mexican-American workers earned significantly less than Anglo workers for the same jobs, lived in company housing without indoor plumbing or hot water, and faced segregated facilities. When Judge Archibald Marshall issued an injunction prohibiting union members from picketing in June 1951, the women of the Ladies Auxiliary voted to take over the picket lines—the injunction only prohibited “union members,” primarily male miners. On June 16, 1951, Sheriff Leslie Goforth arrested 62 people—45 women and 17 children—using tear gas. This extraordinary feminist dimension to the strike made it irresistible material for the filmmakers.

The connection occurred at the San Cristobal Valley Ranch near Taos, New Mexico, in summer 1951, where Paul Jarrico and his family were vacationing. Clinton Jencks and his wife Virginia came to the ranch needing rest from the strike. When Jencks told Jarrico about the women’s picket, the blacklisted producer was captivated. The Jarricos traveled 350 miles south to Hanover to walk the picket lines with the women, then returned to Los Angeles convinced they had found “irresistible motion picture material.”

The bitter irony: unions blocking a pro-union film

Perhaps the cruelest twist in this nightmare production was that Hollywood labor unions refused to allow their members to work on the most pro-labor film ever made in America. As film historian Tom Miller noted in Cinéaste: “That the Hollywood unions wouldn’t let their members work on such a pro-union film was bitter irony.”

Roy Brewer, international representative of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), personally led the opposition. In July 1953, Brewer called the film “one of the most anti-American documentaries ever attempted.” In January 1954, IATSE notified its membership not to handle or project the film. Brewer wrote to Congressman Jackson assuring him: “The Hollywood AFL Council assures you that everything which it can do to prevent the showing of The Salt of the Earth will be done.”

This union opposition forced IPC to assemble a makeshift crew of blacklistees, documentary filmmakers with no feature experience, and inexperienced greenhorns. Only five professional actors were cast; the rest were local miners and their families, including Juan Chacón, the real-life president of Local 890 who worked for Kennecott Copper Corporation. Biberman was initially reluctant to cast Chacón as the male lead Ramón Quintero, thinking him too “gentle,” but Revueltas and others urged him to give Chacón the role. The use of non-professional actors, combined with script approval rights granted to Local 890, produced an authentically collaborative work—but also created enormous production challenges.

The Howard Hughes blueprint for destruction

On March 18, 1953, Howard Hughes, owner of RKO Pictures, wrote a detailed letter to Congressman Jackson that would become, in Jarrico’s words, “a blueprint for suppression.” Hughes outlined specific steps the motion picture industry could take to prevent the film’s completion:

“Before a motion picture can be completed or shown in theatres, an extensive application of certain technical skills and use of a great deal of specialized equipment is absolutely necessary—film laboratories, suppliers of film, musicians and recording technicians, technicians who make dissolves, fades, etc., owners and operators of sound recording equipment and dubbing rooms, positive and negative cutters, [and] laboratories that release prints.”

Hughes concluded: “If the motion picture industry—not only in Hollywood, but throughout the United States—will refuse these skills…the picture cannot be completed in this country.”

The blueprint was executed with precision. Eight laboratories refused to process the film, delaying post-production for months. Jarrico later recalled: “I had to trot around the country with cans of film under my arms, putting the film through different labs under phony names.” The production finally found one lab willing to process footage under the false title “Vaya Con Dios” (Spanish for “Go With God”). Sound tracks had to be recorded as if for a completely different project. The exposed film was developed in secret at night with unmarked canisters delivered to sympathetic lab technicians, who worked in constant fear of discovery.

Sound studios denied access. Editing facilities refused service. Finding musicians willing to record composer Sol Kaplan’s score required subterfuge—Jarrico posed as a representative for a “Mexican film” to rent studio space. The film would use four different editors across four different locations, one of whom turned out to be an FBI informer reporting directly to the Bureau.

Editing in ladies’ rooms and burning shacks

The editing nightmare began in Topanga Canyon, north of Los Angeles, where the first editor—who had only documentary experience—set up in tin-roofed quarters that became so hot the film began to shrivel and physically deteriorate. The production abandoned that location and moved to the ladies’ room of an empty theater owned by Simon Lazarus in Pasadena. When firemen came investigating, they relocated again to a vacant studio in Burbank. For safekeeping, the film was eventually stored “in an anonymous wooden shack in Los Angeles” with elaborate security measures to prevent sabotage or destruction.

HUAC compelled Lazarus, president of Independent Productions Corporation, to testify on March 26-28, 1953, in Los Angeles about his involvement with the company. The committee, “keenly interested in the financing of the film,” sought evidence of foreign funds—particularly Soviet connections—that could justify prosecution under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. They never found any. The film was financed with approximately $95,000 raised from supporters and investors, with cooperation from the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers.

The FBI conducted extensive surveillance throughout production. FBI agents investigated “all actors, writers, stage hands and technical personnel involved in the film” and collected license plate numbers from cars parked near theaters showing the film in Los Angeles. FBI files—227 pages declassified between 1983 and 1989—are preserved at the University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections.

Principal photography ended in March 1953, but post-production didn’t wrap until late 1953, delayed for months by the systematic industry boycott that Hughes had outlined.

Thirteen theaters, a decade of silence

“Salt of the Earth” premiered on March 14, 1954, at the Grande Theatre on 86th Street—the only theater in New York City willing to show it. Before the preview screening, IATSE projectionists refused to run the film, forcing the production to find non-union projectionists.

Across the entire United States, only 12 to 13 theaters exhibited the film initially. By September 1954, that number hadn’t increased. Roy Brewer leveraged his ties with the projectionists’ union to cancel numerous bookings. The American Legion threatened to picket any theater showing the movie. Newspapers refused to publish advertisements. The U.S. House of Representatives formally denounced the film for its Communist sympathies.

The film ran at the Grande Theatre for nine weeks, earning a respectable $50,000, but nationwide distribution was impossible. The filmmakers filed an antitrust lawsuit in 1956 charging more than 100 industry figures with conspiracy. After eight to ten years of litigation, they lost—the jury accepted defendants’ argument that there was no conspiracy since “they had acted individually,” despite overwhelming evidence of coordination.

For a decade, the only chance to see “Salt of the Earth” was at union halls, women’s associations, film schools, and college campuses. The film became an underground organizing tool at labor rallies in Southwestern mining camps, shown in poor-quality 16mm prints to audiences of unionists, feminists, Mexican-Americans, and leftists.

Yet overseas, the film found success. It won the Grand Prix at the 1954 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia, and Revueltas won Best Actress. The film won the International Grand Prize from the Academie du Cinema de Paris in 1955. According to Paul Jarrico, “Salt had probably been seen by more people than any other movie up till then” due to wide distribution in China—it was the only American film screened during Mao Tse-Tung’s time in office. The Russians paid with “potato flour” to distribute it in the USSR.

In May 1959, officials from the United States Information Agency testified before a House Appropriations subcommittee that “Salt of the Earth” was one of a handful of films “giving the United States trouble overseas.” Representative Frank T. Bow (R-Ohio) stated “such films were painting a false picture abroad of the United States and that something should be done about it.”

Vindication, four decades late

The film wasn’t significantly re-released in the United States until 1965—eleven years after its premiere. Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, it found new audiences through the women’s movement, Chicano activism, and renewed interest in labor history. Turner Classic Movies screened it in 1997, significantly raising its profile beyond cult status.

On the crucial turning point came in 1992, when the Library of Congress selected “Salt of the Earth” for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” The film that Congressman Jackson had called “a new weapon for Russia” was now officially recognized as an important part of American cultural heritage.

The copyright wasn’t renewed in 1982, placing the film in the public domain. Today it’s freely available on the Internet Archive, taught in universities nationwide, and screened regularly at labor events. By 2021, Rotten Tomatoes reported a 100% positive rating from critics. In 2000, an opera adaptation called “Esperanza (Hope)” premiered in Madison, Wisconsin, commissioned by the Wisconsin labor movement.

Philosopher Noam Chomsky praised the film in an interview: “I thought Salt of the Earth really did it… one of the really great movies—and of course it was killed, I think it was almost never shown… [It shows] the real work is being done by people who are not known, that’s always been true in every popular movement in history.”

The human cost of resistance

For the filmmakers, vindication came too late or not at all. Herbert Biberman died of bone cancer in 1971, having directed only one more film after “Salt of the Earth.” Michael Wilson died of a heart attack in 1978 at age 63, his credits for “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and “Lawrence of Arabia” not restored until years after his death. Paul Jarrico died in a car crash in 1997, just after receiving honors at a ceremony remembering the blacklist. Rosaura Revueltas never made another American film.

Many participants faced ongoing harassment. Some locals who worked on the film reportedly lost homes to arson, though the local district attorney denied this. Financial losses were never recovered. Health impacts among blacklistees were severe—”premature strokes and heart attacks were fairly common, along with heavy drinking,” according to accounts.

Yet filmmaker James J. Lorence concluded in his 1999 book “The Suppression of Salt of the Earth”: “Salt of the Earth remains an enduring document of Cold War America and an emblem of determined independence. A film little seen in its own time has become a symbol of an alternative vision of America in the 1950s, a view that emphasizes conflict and confrontation… For all the vicissitudes of its troubled history, Salt of the Earth remains a fragile, celluloid monument to that culture of resistance.”

The making of “Salt of the Earth” stands as one of the most comprehensive campaigns of suppression in American film history. Through coordinated action involving Congress (HUAC hearings and House floor denunciations), executive agencies (FBI, INS, State Department, Commerce Department, USIA, CIA), the Hollywood studio system (led by Howard Hughes’ blueprint), labor unions (IATSE, SAG), local vigilantes, and the media establishment, federal officials successfully prevented the film from reaching American audiences for over a decade—without ever filing formal charges against the filmmakers.

That the film was completed at all testifies to the courage and determination of people who, having already lost everything to the blacklist, decided to make the most subversive film they could imagine. As Paul Jarrico put it: “We wanted to commit a crime to fit the punishment.” The production nightmare became inseparable from the film itself, transforming “Salt of the Earth” into an act of political and artistic resistance that would inspire generations of independent filmmakers to come.

Podcasts & Audio Dramatization

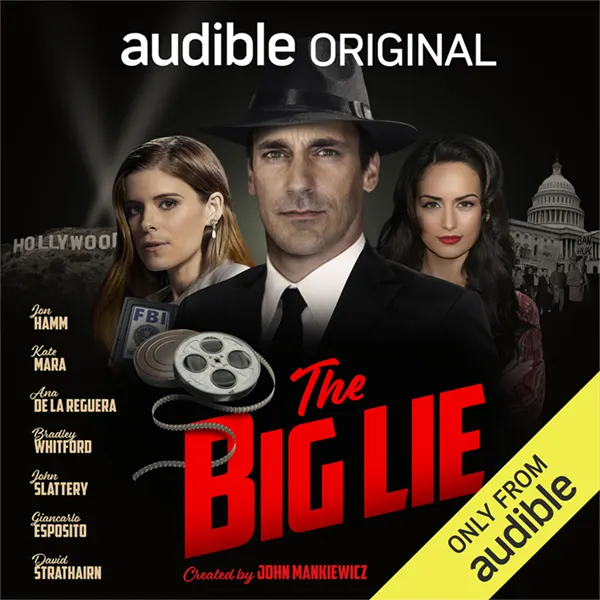

The Big Lie follows FBI special agent Jack Bergin (Jon Hamm), who is sent to investigate three blacklisted filmmakers—Academy Award-winning writer Michael Wilson, Academy Award-nominated producer Paul Jarrico, and director Herbert J. Biberman—who were inspired by a New Mexico labor strike to make a movie that dramatized their pro-labor, pro-feminist beliefs. Convinced the film is a recruitment tool for the Communist Party, Jack will do whatever is necessary to shut the production down.

Featuring a star-studded cast that also includes Giancarlo Esposito, David Strathairn, Lisa Edelstein, Raymond Cruz, Troy Evans, Kirk Baltz, John Getz, and Lela Loren, The Big Lie is an explosive story of conspiracy, betrayal, and temptation that resonates with today’s divided America and reminds us all that fear spreads faster than the truth.

Created by John Mankiewicz, based on a story from Paul Jarrico.

Reference & Encyclopedia Sources

- Salt of the Earth (1954 film) – Wikipedia

- Rosaura Revueltas – Wikipedia

- Herbert Biberman – Wikipedia

- Paul Jarrico – Wikipedia

- Michael Wilson (writer) – Wikipedia

- Will Geer – Wikipedia

- Empire Zinc strike – Wikipedia

- Hollywood blacklist – Wikipedia

- Hollywood Ten – Encyclopedia Britannica

- Paul Jarrico – Encyclopedia.com

- Salt of the Earth – Encyclopedia.com

- HUAC, the Blacklist, and the Decline of Social Cinema – Encyclopedia.com

News & Journalism

- A Film Back From the Blacklist – The Washington Post

- Why ‘Salt of the Earth’ was a truly subversive film – The Forward

- The Insane Saga of ‘Salt of the Earth,’ the Only Film to Be Blacklisted – The Daily Beast

- Cinema: Salt of the Earth – TIME

- What an Epic Women’s Strike Can Teach Us Over 70 Years Later – The Nation

Academic & Educational Resources

- Salt of the Earth – Zinn Education Project

- March 14, 1954: Salt of the Earth Premieres – Zinn Education Project

- Salt of the Earth by Herbert Biberman (1954) – Michigan Tech

- Why suppress Salt of the Earth – Michigan Tech

- Salt of the Earth (1954): The Ultimate Red Scare Counter-Narrative – UCL Film & TV Society

- Herbert Biberman – Spartacus Educational

- Production – Salt of the Earth: A Teaching & Learning Resource

Film Databases & Reviews

- Salt of the Earth (1954) – Turner Classic Movies

- Salt of the Earth (1954) – Letterboxd

- Salt of the Earth (1954) – IMDb

- Will Geer – The Movie Database (TMDB)

- Salt of the Earth – Film Reference

Labor & Political Publications

- Salt Of the Earth – Labor Films

- Michael Wilson’s ‘Salt of the Earth’ script, miracle of the blacklist era – People’s World

- Salt of the Earth continues to inspire – People’s World

- Celebrating the 70th Anniversary of Salt of the Earth – CovertAction Magazine

- Celebrating the 70th anniversary of ‘Salt of the Earth’ – MR Online

- “Salt of the Earth” – blacklisted! – Jewish Voice for Labour

- Salt of the Earth – libcom.org

Archives & Special Collections

Historical & Analysis Articles

- Salt of the Earth: The Movie Hollywood Could Not Stop – HistoryNet

- The Hollywood Ten – Bleecker Street

- The Hollywood Ten: The Men Who Refused to Name Names – The Hollywood Reporter

- Hollywood Tried To Erase Lawrence Of Arabia’s Writer From History – SlashFilm