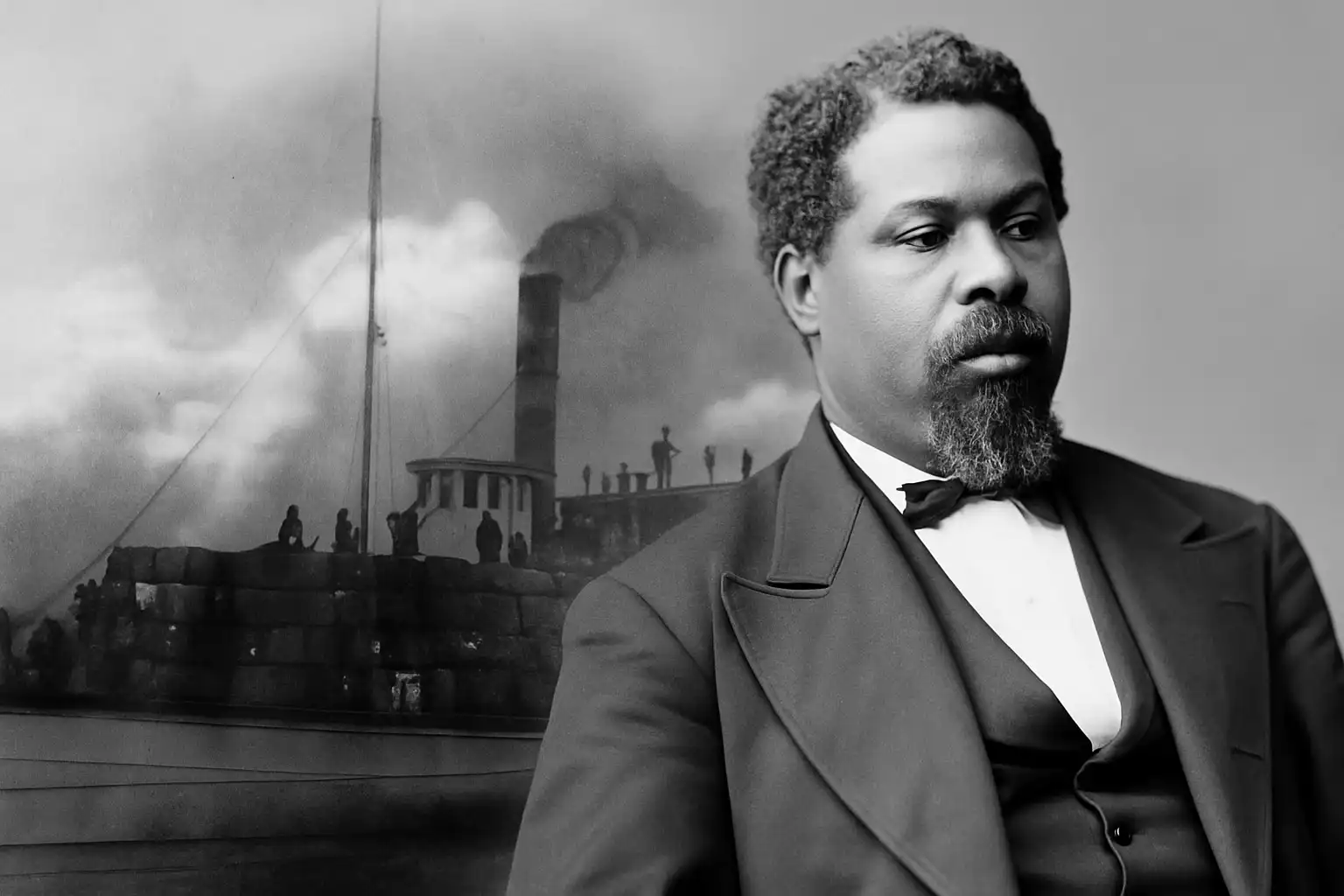

Executive Summary: The Arc of Robert Smalls (1839–1915)

Robert Smalls’ extraordinary life details a profound journey from the depths of chattel slavery to the heights of American politics and military distinction, encapsulating the transformative possibilities and the enduring racial barriers of the 19th century. Born into bondage in 1839, his seminal act of heroism—the commandeering of the Confederate steamship Planter on May 13, 1862—immediately catapulted him to national fame and secured freedom for himself, his crew, and their families. This operation was not a mere stroke of luck, but a sophisticated military defection enabled by Confederate operational negligence and Smalls’ unparalleled maritime skill.

Following his wartime service as the first African American captain of a United States vessel, Smalls transitioned into a foundational Republican statesman during the Reconstruction era. His political career involved pioneering legislation that established South Carolina’s first system of free, compulsory public education for all children and securing critical property rights for formerly enslaved citizens. Serving multiple terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and concluding his career as a long-standing U.S. Collector of Customs, Smalls became one of the most prominent African American leaders of his time, constantly fighting against the forces of disfranchisement and racial oppression that culminated in the Jim Crow era. His successful navigation of these volatile periods remains a testament to his intelligence, bravery, and unwavering commitment to securing equality.

I. Origins and Apprenticeship: Forging a Master Pilot (1839–1861)

I.A. Enslavement and the Lowcountry Environment

Robert Smalls was born into slavery on April 5, 1839, in Beaufort, South Carolina. His mother, Lydia Polite, was a slave owned by Henry McKee, a local planter. Smalls spent his earliest years living in a small slave cabin behind the McKee house at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort. Though he worked in the house with his mother, Lydia Polite had grown up working in the fields and feared that her son might grow up oblivious to the true, brutal nature of slavery suffered by the plantation hands.

In a desperate attempt to educate him on the full horrors of their condition, Lydia deliberately exposed the young Robert to the sights of field hands being whipped—a frequent occurrence on the plantation. This deliberate act of exposure had an immediate effect, fueling Smalls’ youthful defiance, which often led to him being confined in the Beaufort jail. Fearing for her son’s safety due to his rebellious nature, Lydia arranged with Henry McKee to have Robert sent away to Charleston to be “hired out”. This relocation proved to be the pivotal decision of Smalls’ early life. The strategy, intended to protect him from the immediate dangers of the plantation system, inadvertently placed him in the specialized urban labor environment necessary to acquire the highly valuable operational skills that would later enable his sophisticated act of self-emancipation.

I.B. Acquisition of Maritime Expertise and Personal Stakes

Beginning at age 12, Smalls worked various jobs in Charleston under the “hiring out” system, sending the majority of his meager earnings back to his master. For the next decade, Smalls worked extensively around Charleston Harbor, serving as a waiter, lamplighter, stevedore, sailmaker, and rigger. Through sheer experience, he grew intimately familiar with the complex tidal patterns, currents, and dangerous sandbars of the harbor.

By the time he was 17, Smalls possessed the practical knowledge necessary to handle the wheel and navigate a boat proficiently. Although racial custom prevented him from holding an official pilot title, his skills were undeniable. When he was assigned to the Confederate steamer Planter, the ship’s three white officers relied entirely upon Smalls to safely maneuver the vessel around the harbor, demonstrating the high degree of trust and competence he had earned through practical mastery.

Smalls’ personal stakes in freedom intensified with his family. He married Hannah Jones, an enslaved hotel maid, on December 24, 1856, and they had two children, Elizabeth and Robert Jr.. Smalls attempted to purchase his family’s freedom, saving money through an agreement with his master. However, Hannah’s owner demanded $800 for her freedom—a cost so prohibitive that Smalls recognized it would take him years to save the necessary capital. This personal failure to secure his family through legal means solidified his promise to Hannah that they would one day escape from slavery through a far more daring method.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Smalls was assigned to the CSS Planter, a 147-foot sidewheel steamer built in 1860. The vessel was owned by John Ferguson but leased to the Confederate Army, under the command of Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley, and was utilized for critical Confederate defense operations, including dispatch, troop, and arms transport, as well as laying and maintaining harbor defenses. During his tenure, Smalls carefully monitored the network of Confederate harbor defenses and noted the proximity of the Union naval blockade outside Charleston Harbor.

II. The Daring Gambit: Commandeering the CSS Planter

II.A. The Confederate Vessel and Crew

The Planter was a highly valuable military asset, armed with a 32-pound pivot gun on the bow and a 24-pound howitzer astern. Smalls and the other enslaved crewmen were trained to use these weapons. The crew consisted of three white officers—Captain Charles Relyea, First Officer Samuel Hancock, and Engineer Samuel Pitcher—and seven enslaved African American crew members: Robert Smalls (Helmsman/Pilot), John Small (Engineer), Alfred Gourdine (Engineer), and deckhands Abraham Jackson, Gabriel Turner, David Jones, and Jack Gibs.

Smalls recognized that any escape attempt required a commitment to collective liberation. He held secret meetings with the crew and several other enslaved individuals attached to nearby vessels and posts, including Charles Chisolm, William Morrison, and Abram Allston. The plan mandated that they would collect their families and sail the vessel toward the Union blockade under the cloak of the pre-dawn darkness and fog.

II.B. A Confluence of Negligence: Incidents Conspiring to Freedom

The successful capture of the Planter was predicated on a precise alignment of operational and security lapses by the Confederate command, combined with Smalls’ intelligence and audacity. These incidents conspired to create a singular window of opportunity on May 13, 1862.

First, Smalls correctly calculated that the white officers would leave the ship unattended after returning from two weeks of setting up artillery on James Island. On the evening of May 12, the three white officers went ashore to Charleston to spend the night with their families. This action flagrantly violated Confederate naval policy, which strictly required at least one officer to remain aboard the vessel at all times. The root cause of this operational negligence lay in the officers’ belief that the enslaved crew was inherently incapable of any treachery. This profound racial blind spot—the core ideology of slavery—directly compromised Confederate security, transforming Smalls’ highly trained maritime skill set from an asset into a fatal vulnerability.

Second, Smalls was aware that the Confederate guard boat responsible for patrolling and protecting the entrance to the inner harbor was “out of commission” at that time. This critical military failure provided a momentarily unguarded path out of the most heavily fortified zones of Charleston Harbor.

Third, the window of opportunity was strictly limited by a major military announcement: Confederate forces were scheduled to implement martial law in Charleston the following day, May 13. Smalls understood that escaping after the declaration of martial law would have dramatically increased the risk of discovery and capture, demanding immediate execution of the plan.

These factors—officer negligence, a disabled guard boat, and the impending deadline of martial law—created the necessary military environment for the plan to proceed.

Table 1: Key Factors Enabling the CSS Planter Escape (May 12–13, 1862)

Factor Category

Specific Incident/Condition

Strategic Advantage for Smalls

Insider Knowledge

Smalls’ intimate knowledge of Charleston Harbor’s channels, tides, and Confederate signaling procedures.

Enabled precise navigation through heavily fortified areas (Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie).

Confederate Negligence

White officers routinely violated standing orders by sleeping ashore instead of remaining aboard the vessel.

Left the enslaved crew, including Smalls and engineers, alone and unsupervised on a high-value military transport ship.

Operational Timing

The Confederate guard boat protecting the inner harbor entrance was temporarily out of commission.

Provided a critical, brief window to exit the most heavily monitored zone undetected.

Urgency of Timeline

Martial Law was announced to take effect the following day (May 13).

Martial Law was announced to take effect the following day (May 13).

II.C. Execution and Passage to Freedom

At approximately 3:00 AM on May 13, 1862, Smalls and his fellow freedom seekers fired up the ship’s boilers and eased the vessel away from the Southern Wharf, positioned right next to the headquarters of Confederate General Roswell S. Ripley. They proceeded to a nearby wharf where they picked up the waiting family members, bringing the total number of freedom seekers aboard to sixteen men, women, and children.

The most perilous leg of the journey required them to steam directly past the Confederate garrisons at Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie. Utilizing his experience as a pilot, Smalls donned the white captain’s hat, mimicking the mannerisms of Captain Relyea, and expertly guided the steamer through the inner harbor. Crucially, Smalls “knew the proper signals to give” to the unsuspecting rebel sentries at the fortifications, allowing the Planter to receive clearance and pass unchallenged.

After safely navigating the heavily defended harbor, Smalls piloted the group ten miles out to the Union naval blockade. He surrendered the vessel and its cargo—which included several cannons—to the USS Onward. The captured vessel and its intelligence immediately impressed the Union command. Flag Officer Samuel Francis Du Pont described Smalls as “superior to any who have come into our lines—intelligent as many of them have been”. The daring feat was celebrated in the national press, with the New York Herald calling it “one of the most daring and heroic adventures since the war was commenced”. The capture was also a significant military blow to the Confederacy, which lost a valuable armed steamer and sorely needed artillery.

III. Service in Blue: Robert Smalls as Union Pilot and Captain (1862–1866)

III.A. Wartime Contribution and Strategic Intelligence

Smalls’ value to the Union extended far beyond the delivery of the Planter. His intimate, local knowledge of the South Carolina Sea Islands, including channels, fortifications, and troop locations, was immediately leveraged by the Union Navy. The intelligence Smalls provided directly contributed to the Union’s ability to capture Coles Island outside of Charleston Harbor without a fight. Smalls spent the remainder of the war serving as a Union naval pilot, first guiding the captured Planter, which was refitted as a troop transport, and later serving aboard the ironclad ship USS Keokuk and the USS Crusader.

III.B. The Valor of the Captaincy

Smalls’ reputation for valor was cemented during an engagement on December 1, 1863. While piloting the Planter, the ship became caught in a heavy crossfire between Union and Confederate forces. The ship’s commander, Captain Nickerson, lost his resolve and ordered the crew to surrender. Smalls immediately refused this order, stating that he feared he and the black crewmen would not be afforded prisoner of war status by the Confederates and would likely be executed summarily. Smalls bravely assumed command, seized control of the vessel, and expertly piloted it out of the range of the Confederate guns, saving the ship and its crew. As a reward for this extraordinary act of courage and leadership under fire, Smalls was appointed Captain of the Planter on December 1, 1863, a civilian appointment that nonetheless recognized his military authority. He became the first black man to officially command a United States vessel, a position he retained until the Planter was sold by the Army in 1866.

III.C. Broader Impact on Union Policy

The widespread notoriety surrounding Smalls’ escape and his subsequent effectiveness as a pilot and captain had far-reaching implications for Union policy. His demonstrable intelligence and capability, praised by high-ranking officers like Du Pont, provided powerful evidence of the competency of formerly enslaved individuals in command roles. His example and persuasive powers are recognized as having helped convince President Abraham Lincoln to officially accept African American soldiers into the Union Army, significantly bolstering the Union war effort and accelerating the mobilization of the U.S. Colored Troops. Smalls’ success served as a powerful recruiting tool, illustrating that service in the Union cause offered a direct path to personal liberty and heroic achievement.

IV. The Architect of Reconstruction: Political Ascendancy and Economic Self-Determination (1864–1879)

IV.A. Early Activism and Defining Property Rights

Even before the Civil War concluded, Smalls began his career as an advocate for civil rights. While serving as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in 1864, he was arrested for riding in a segregated streetcar. In response, Smalls organized a successful boycott that ultimately led to the desegregation of Philadelphia’s transit system in 1867, demonstrating his organizational acumen and commitment to equal treatment.

Following the capture of Beaufort by the Union, Smalls returned to his native district. In January 1864, he achieved a profound symbolic and legal reversal by purchasing his former master’s home (the McKee house) for $605, after it was seized and sold for back taxes. When his ownership was challenged in 1875 by the former ruling class (De Treville vs. Smalls), Smalls fought the lawsuit all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and prevailed. This legal success was crucial; it served as a vital test case that helped to define and protect the newly established property rights of formerly enslaved individuals against attempts by previous owners to reclaim assets during the Reconstruction era. This act was not merely personal acquisition; it provided validation that Black citizens could legally secure and maintain ownership of valuable property, effectively inverting the power structure that had defined his youth.

IV.B. State Legislative and Economic Achievements

Smalls became a foundational figure in the political landscape of the South. He was a founder of the South Carolina Republican Party and quickly moved into legislative service. He was a delegate to the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention and subsequently served in the South Carolina House of Representatives (1868–1870) and the South Carolina Senate (1870–1875).

His most significant legislative contribution was authoring the state legislation that established South Carolina’s first system of free and compulsory public schools for all children, regardless of race. Having enhanced his own literacy through camp schools during the war, Smalls understood the necessity of education for the advancement of the newly freed population. Although he initially supported a controversial poll tax to fund this system—a stance that briefly placed him at odds with some African American leaders who feared the tax would disproportionately affect the poor—Smalls viewed the tax as a necessary, pragmatic measure to ensure the financial viability of universal education.

Beyond politics, Smalls demonstrated significant economic leadership. In 1870, anticipating the prosperity of Reconstruction, Smalls, along with other African American representatives, co-founded the Enterprise Railroad. This 18-mile horse-drawn railway line, which carried cargo and passengers near Charleston, had an almost entirely African American board of directors (except for one white “Carpetbagger” director). This venture was lauded as “the most impressive commercial venture by members of Charleston’s black elite,” demonstrating Black capacity for major infrastructural and economic self-determination. Smalls also served in the South Carolina State Militia, rising in rank from Lieutenant-Colonel to Brigadier-General and eventually to Major-General of the Second Division, a sign of the high political stature he commanded in the state until Democrats retook control in 1877.

IV.C. Congressional Service and The Jim Crow Assault

Smalls was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, serving multiple, non-consecutive terms between 1875 and 1887. During his tenure, he leveraged his national platform to champion civil rights, land ownership for freedmen, and anti-discrimination laws, laying the groundwork for future civil rights advancements.

However, the late 1870s marked the systematic dismantling of Reconstruction. Smalls faced intense opposition, including systemic barriers aimed at suppressing African American political power and violence from white supremacist groups. In 1877, Smalls was convicted on a bribery charge—a conviction rooted in the political corruption and targeted prosecution of Republican officials common during this period—though he was pardoned by the Governor of South Carolina in 1879.

Smalls’ career perfectly illustrates the fragility of the gains made during Reconstruction. His experience paralleled the observation made by W.E.B. Du Bois that the formerly enslaved “stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery”. Despite these immense pressures and the rise of Black Codes and Jim Crow, Smalls refused to succumb to pessimism. He challenged the legislature, declaring, “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life,” a powerful declaration of inherent equality that endures as his legacy.

Table 2: Robert Smalls’ Major Roles and Service (1862–1913)

May 1862

Pilot – Union Navy

Commandeered the Planter and gained national notoriety.

Dec 1863–1866

Captain of the Planter (Civilian) – Union Army

First Black man to command a US vessel; earned command through wartime valor.

1868–1870

SC House of Representatives (Republican)

Championed universal suffrage and free public education.

1870–1875

SC Senate (Republican)

Authored state’s first compulsory public school legislation.

1875–1887

U.S. House of Representatives (Republican)

Served three non-consecutive terms, fighting against disfranchisement and for civil rights.

1889–1913

U.S. Collector of Customs

Presidential appointee, holding a significant federal post during the Jim Crow era.

V. National Service, Decline of Reconstruction, and Final Legacy (1880–1915)

V.A. Federal Appointments and Final Political Battles

Smalls’ influence endured through the final decades of the 19th century, even as white Democrats regained control of the South. He secured a significant federal appointment, serving multiple terms as the U.S. Collector of Customs for the Port of Beaufort (1889–1893 and 1897–1913). Maintaining this prominent federal position for nearly two decades, despite the prevailing anti-Black political atmosphere, cemented his reputation as a formidable political figure.

His final major political confrontation occurred in 1895 when he delivered an impassioned defense of Black rights before the South Carolina constitutional convention. Smalls attempted to halt the passage of sweeping measures designed explicitly to systematically strip Black men of the franchise. Although unsuccessful in the face of overwhelming white Democratic power, his efforts exemplified the resilience and agency of African American leadership striving against enduring inequality.

Smalls passed away in his Beaufort home—the same house he had purchased from his former master—on February 23, 1915, having lived through the full cycle of slavery, freedom, political ascent, and the severe racial retrenchment of the Jim Crow era. His political life provided a powerful counter-narrative to the ideology of white supremacy, proving the capability of Black leadership in the highest offices of government. For his exceptional wartime service, Congress officially granted him a pension equal to that of a Navy captain in 1897.

V.B. The Fate of the Planter and Crew

The vessel that brought Smalls and his crew to freedom continued to serve the Union Army until 1866. A decade later, on March 25, 1876, the USS Planter was lost. While attempting to tow a grounded schooner, the steamer sprang a plank and began taking on water. Despite beaching the vessel to attempt repairs, stormy seas battered the Planter, and it had to be abandoned near Cape Romain, South Carolina. Upon receiving the news of the shipwreck, Robert Smalls reportedly felt as though he had lost a member of his own family, underscoring the deep emotional connection he held to the instrument of his liberation.

The success of the May 1862 escape was a testament to the collective risk taken by the entire crew and their families. While Smalls became the figurehead, engineer John Small worked closely with Alfred Gourdine to operate the vessel’s machinery, securing the freedom of his own wife, Susan, and infant son, Phillip, alongside the other 13 passengers. The collective nature of the plan emphasizes that the strike for freedom was an organized military and family operation involving sixteen people.

VI. Enduring Legacy and Verification of Cultural Footnotes

VI.A. Modern Recognition

Robert Smalls’ legacy is honored throughout American military and civil history. In 2007, the U.S. Army commissioned the USAV Major General Robert Smalls, marking the first Army ship named for an African American. Smalls’ home in Beaufort remained in the family until the 1950s and was later recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1974, preserving the tangible symbol of his victory over his former master. His career, marked by transformative legislation on education and a defiant stance against racial injustice, established him as a paramount historical figure in the history of American democracy and civil rights.

VI.B. Verification of Pop Culture Claims: The “Smalls” Moniker

The inquiry suggests that the famous rapper Notorious B.I.G., known also as Biggie Smalls, and a Chicago gangster were named after the historical figure Robert Smalls.

Notorious B.I.G. (Christopher Wallace)

The claim that Christopher Wallace’s stage name, Biggie Smalls, derives from Robert Smalls is factually incorrect. Research indicates that Christopher Wallace adopted the moniker Biggie Smalls from a character in the 1975 film Let’s Do It Again, where the role of the lead gangster, Biggie Smalls, was played by actor Calvin Lockhart. Wallace was subsequently threatened with legal action by another young rapper, Tim Bigelow, who was already performing as “Biggy Smallz”. Consequently, Christopher Wallace was forced to change his stage name to The Notorious B.I.G. (where B.I.G. sometimes stood for Business Instead of Gain) to avoid legal entanglement. The connection to Robert Smalls, while often assumed due to the historical figure’s fame and the rapper’s prominent status, is rooted in cinematic fiction rather than direct historical inspiration.

The Chicago Gangster Claim

The collected historical and biographical materials concerning Robert Smalls provide no documented evidence or third-party verification linking his name directly to a prominent figure in Chicago criminal history. Given the prevalence of historical misattribution, particularly in associating a figure with a name that became famous through the Notorious B.I.G. alias, the absence of data strongly suggests this claim is likely an unsubstantiated rumor or an extension of the established pop culture confusion surrounding the origins of the “Smalls” moniker.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Audacity and Institution Building

Robert Smalls’ life serves as a definitive case study in self-emancipation and the political mobilization of newly freed populations. His success was achieved through the sophisticated synthesis of unique maritime skills acquired through slavery, combined with an unflinching willingness to exploit the structural vulnerabilities and ideological blind spots of the Confederate command structure.

His subsequent career, defined by military heroism, economic endeavor (the Enterprise Railroad), and legislative achievements (compulsory public education), established the crucial foundation for Black political and economic power in Reconstruction-era South Carolina. Though his later career was shadowed by the systematic erosion of civil rights, Smalls’ determined refusal to concede the principle of racial equality, encapsulated in his powerful rhetoric, left a legacy of resilience that continues to resonate today. His achievements, spanning naval command, political leadership, and property rights defense, confirmed that African Americans required only “an equal chance in the battle of life” to prove themselves the equal of any people anywhere.

Biographical Overviews

- Robert Smalls – U.S. National Park Service

- Robert Smalls – Wikipedia

- Robert Smalls | Biography, Accomplishments, & Facts – Britannica

- Robert Smalls – National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

- Robert Smalls – African American History Since 1865 – Fiveable

- Black History Month: Why Remember Robert Smalls? – Lee & Low Books

The Steamship Planter and the Civil War

- Robert Smalls and the Steamship Planter: Turning the Tides for the Union – Gettysburg College

- Robert Smalls and the Planter – American Battlefield Trust

- The Planter – U.S. National Park Service

- The “Planter”: A Strike for Freedom – Reconstruction Era National Historical Park

- NOAA Identifies Probable Location of Iconic Civil War-Era Steamer

- USS Planter (1860) – Wikipedia

- Fighting for Freedom: Black Union Soldiers of the Civil War – City of Alexandria, VA

- Military Series – Robert Smalls – Southern Delaware Alliance for Racial Justice

Reconstruction and Later Life

- Robert Smalls and Reconstruction Politics – AAIHS

- Former Slave Bought His Master’s House and Served as Collector of Customs – U.S. Customs and Border Protection

- Robert Smalls Pt. 3: After the Civil War – Beaufort.com

- Robert Smalls: From Escaped Slave to Congressman – PBS

- The Robert Smalls House – U.S. National Park Service

- From Slave to Hero to Congressman: The Big Story of Robert Smalls – The Saturday Evening Post