Overview

Matt Baker was the most talented comic book artist you’ve never heard of — a gay Black man who became the Golden Age’s premier illustrator of women, created the first graphic novel, and had his art weaponized in Congress to censor an entire industry, all while maintaining perfect composure in silk ties and a yellow convertible.

“Matt Baker was one of the first important artists in comics. Not one of the first important black artists, one of the first important artists, period.”

-Jerry Iger

Born in 1921 North Carolina and dead by 37, Baker achieved what should have been impossible: becoming comics’ most sought-after artist during an era when merely speaking to a white woman could have gotten him killed. His work directly influenced

creators from Dave Stevens to Adam Hughes, yet for decades his name vanished from comics history while less talented white contemporaries became legends. The story of how Baker navigated these intersecting barriers — and why his genius is only now being recognized — reveals both the profound creativity and devastating erasure that defined America’s early pop culture.

Breaking into an industry that didn’t want him to exist

When 23-year-old Clarence Matthew Baker walked into Jerry Iger’s Manhattan studio in 1944, he carried a single color sketch of a beautiful woman. The comics industry ranked “just above pornography” in professional respectability, as Will Eisner later admitted, and was “almost totally dominated by white males,” according to colleague Al Feldstein. For a Black artist, the barriers were essentially insurmountable — legal segregation prevented Black creators from working in mainstream studios until 1957, and Southern distributors would boycott books if they discovered Black involvement. Yet Baker had two things working in his favor: childhood rheumatic fever had damaged his heart, exempting him from military service when other artists were drafted, and his artistic talent was so exceptional it overcame institutional racism.

Baker had prepared meticulously for this moment. After graduating from high school in Pittsburgh in 1940, he worked for the government in Washington D.C. while studying the techniques of magazine illustrator Andrew Loomis and comics masters Will Eisner and Reed Crandall. By 1943, he’d moved to New York and enrolled at the prestigious Cooper Union School of Art. His strategy for overcoming bias was deliberate: he dressed impeccably in broad-shouldered double-breasted suits with matching fedoras, spoke softly, and as Feldstein observed, “did not talk openly about his position as a Black man in an almost all white field, but instead let his talent talk for him.”

The Iger Studio, which produced ready-to-print comic pages for multiple publishers, became Baker’s entry point. Ruth Roche, the associate editor who would become his most important collaborator, advocated for his hiring. Initially relegated to drawing backgrounds and inking other artists’ women — with the credit going to them — Baker gradually proved indispensable. His first confirmed published work appeared in Fiction House’s Jumbo Comics #69 (November 1944), penciling the female figures in a Sheena, Queen of the Jungle story. Within a year, he’d created Voodah for Crown Comics #3, the first known Black superhero in American comics, though publishers later recolored the character as white to avoid controversy.

The artistic revolution hidden in “good girl” art

Baker’s distinctive style transformed what critics dismissively called “good girl art” into something approaching fine illustration. His female figures possessed what contemporary observers described as “almost tangible energy” — they seemed to “dance and slide and shimmy from panel to panel” with anatomical precision that colleague Bob Lubbers insisted “could only come from exhaustive personal research.” Unlike his contemporaries who drew women as decorative accessories, Baker created what one analysis calls “classy, realistic beauties, equally full of character and starring in their own stories.”

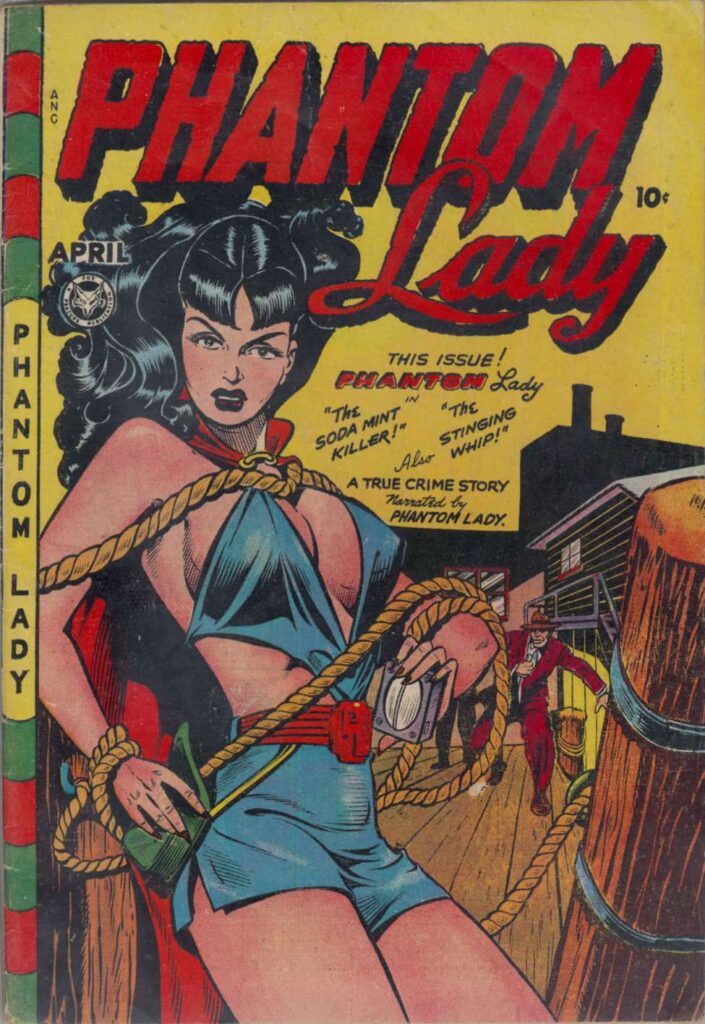

Recent scholarship by Monalesia Earle has uncovered sophisticated technical innovations in Baker’s work. He employed deliberate “misdirection” in panel layouts, using body parts extending beyond frame borders to create unconventional viewing paths — a subtle artistic rebellion from his marginalized position. His mastery extended beyond technique to characterization. When he redesigned Phantom Lady in 1947 for Fox Comics, he didn’t just change her costume from a modest green cape and yellow outfit to revealing blue shorts with a plunging halter top; he reconceived her as a character whose sexuality was strategic, using her appearance to distract male opponents while maintaining agency in her own adventures.

Between 1948 and 1954, Baker’s peak years at St. John Publications, he produced over 1,000 individual comic pages and more than 200 covers — an almost superhuman output achieved through punishing work habits. Friends described him working “all hours of the night” in his fifth-floor Manhattan walk-up, chain-smoking Camels at his drawing board while Billie Holiday played on his phonograph, often working “for days on end before collapsing into several days of sleep.” His productivity was even more remarkable given his heart condition left him struggling for breath after climbing stairs.

Creating the first graphic novel while hiding in plain sight

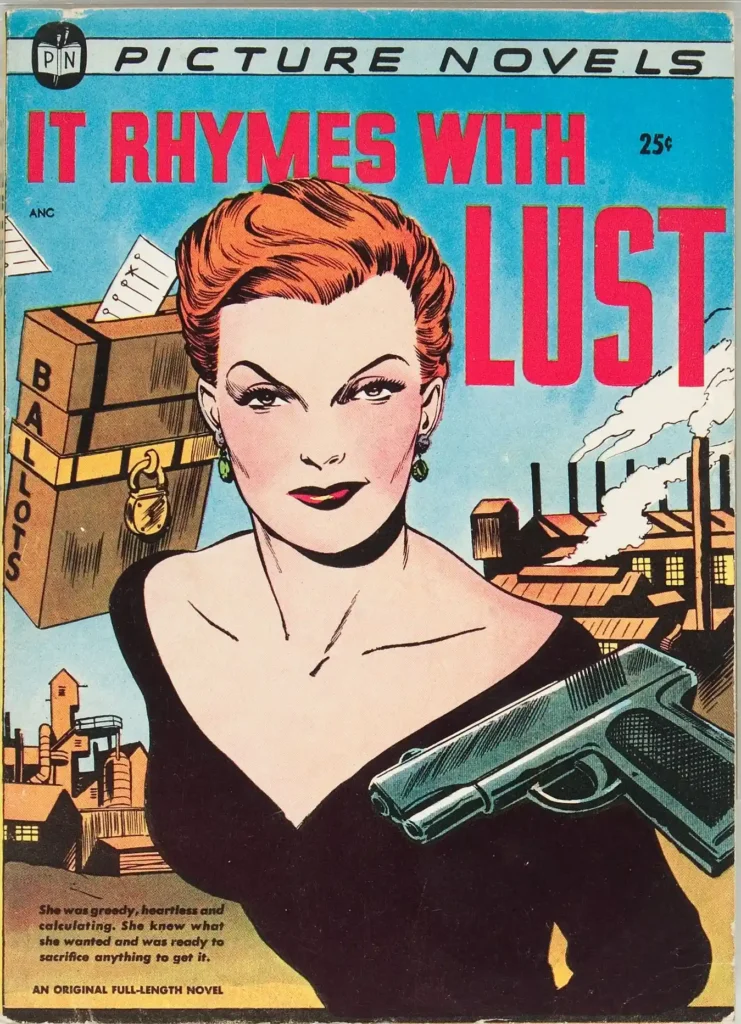

In 1950, Baker penciled “It Rhymes with Lust,” a 128-page digest-sized “picture novel” that predated the term “graphic novel” by decades. Working with writers Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller (writing as “Drake Waller”), Baker illustrated a noir thriller about political corruption, greed, and sexual manipulation in the fictional Copper City. The format was revolutionary — Drake and Waller conceived it as “a deliberate bridge between comic books and book books,” targeting adult readers beyond the traditional comics audience.

In 1950, Baker penciled “It Rhymes with Lust,” a 128-page digest-sized “picture novel” that predated the term “graphic novel” by decades. Working with writers Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller (writing as “Drake Waller”), Baker illustrated a noir thriller about political corruption, greed, and sexual manipulation in the fictional Copper City. The format was revolutionary — Drake and Waller conceived it as “a deliberate bridge between comic books and book books,” targeting adult readers beyond the traditional comics audience.

The story centered on Rust Masson, a scheming widow using her sexuality and violent henchmen to control the city’s political machine, with her former lover, newspaperman Hal Weber, caught in her web. Baker’s art elevated the pulp material through sophisticated visual storytelling that influenced the entire noir comics genre. Yet despite its historical significance as the first graphic novel, Baker received minimal recognition during his lifetime. The work has been reprinted multiple times since, including a 2007 Dark Horse edition, finally acknowledging its groundbreaking nature.

When Congress used his art to destroy comics

The image that changed American pop culture forever appeared on the cover of Phantom Lady #17 in April 1948: Baker’s illustration of the heroine bound to a post, chest thrust forward in her revealing blue costume. Dr. Fredric Wertham, a German-born psychiatrist who had previously done important work supporting racial integration, seized upon this single image for his 1954 book “Seduction of the Innocent.” His caption read: “Sexual stimulation by combining ‘headlights’ with the sadist’s dream of tying up a woman.”

Wertham testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency that comics were “worse than Hitler,” claiming they caused juvenile delinquency, homosexuality, and violent crime. The Phantom Lady cover became Exhibit A in his congressional testimony. By October 1954, the Comics Code Authority was established, requiring that “all characters shall be depicted in dress reasonably acceptable to society.” Within months, Comics Code administrator Charles Murphy had altered 5,656 comic book drawings, with 25% changed specifically to “de-emphasize feminine curves.”

The supreme irony wasn’t lost on later historians: a gay Black artist’s work had been weaponized in a white moral panic that destroyed careers and bankrupted publishers. Even more ironically, University of Illinois researcher Carol Tilley’s 2012 investigation of Wertham’s sealed papers revealed he had “manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence.” One supposed Batman-obsessed patient was actually a Superman fan who had been sexually abused — facts Wertham deliberately omitted. Quotes from one child were attributed to five different patients. The entire moral panic that reshaped American comics was based on professional fraud.

Remarkably, Baker himself faced no direct career backlash. He continued working through the 1950s, freelancing for Atlas Comics (later Marvel) on westerns and science fiction until a 1957 stroke affected his drawing ability. On August 11, 1959, the damaged heart that had kept him out of World War II finally failed. Baker died at 37, before he could see his vindication.

The influence that couldn’t be erased

Dave Stevens, creator of The Rocketeer, explicitly cited Baker among his major influences, placing him alongside Will Eisner and Lou Fine in the pantheon of Golden Age masters. The connection was aesthetic and philosophical — both artists specialized in anatomically precise, glamorous women who maintained character agency. Stevens’ signature character Betty, modeled after Bettie Page, carried forward Baker’s tradition of “good girl art” that respected its subjects. Contemporary artist Adam Hughes continues this lineage, acknowledging both Baker and Stevens as foundational influences.

Yet while Stevens and Hughes became celebrities, Baker remained largely unknown outside specialist circles. His contemporaries Will Eisner and Jack Kirby, who lived into their 70s and 80s, had decades to cement their legacies and tell their stories. Baker’s early death meant no interviews, no convention appearances, no autobiographical works. The genres he mastered — romance comics and “good girl art” — were critically dismissed as juvenile or exploitative. His race compounded the erasure; as Ken Quattro’s research revealed, white media virtually ignored Black comic artists’ contributions, while Black newspapers that covered Baker weren’t systematically archived.

The numbers tell the story: despite producing over 1,000 pages and 200 covers in just his peak six years, despite creating the first graphic novel and the first Black superhero, despite his art being literally presented to Congress as evidence of comics’ power, Baker didn’t receive industry recognition until 2009, when he was posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame — fifty years after his death.

A gentleman in an ungentlemanly business

“He could have been a movie star or a model,” recalled colleague Bob Lubbers, describing Baker’s impressive physical presence and impeccable style. Standing 5’10” with what friends called a “dark-coffee complexion” and “gentle, closed-mouth smile,” Baker drove a canary yellow convertible Oldsmobile through Manhattan and owned at least four fedoras — brown, black, green, and maroon — matched precisely to his suits. Arnold Drake called him “the hippest dresser I had ever seen.”

But Baker’s stylish exterior masked complex realities. Multiple colleagues, including close friend Frank Giusto and artist Lee J. Ames, confirmed Baker was gay — Giusto explicitly stated: “I knew he was gay because of some of the people he hung around with and the parties he went to.” In an era when homosexuality was illegal and Black men faced violence for any perceived sexual interest in white women, Baker navigated treacherous intersections. As one biographer noted, he was “a damn good-looking black man who made his living drawing damn good-looking white women at a time when talking to one could have gotten him killed.”

His isolation was pronounced. While white colleagues went to lunch together, Baker “would go off on his own,” acutely aware of what Feldstein called “the perceived chasm that separated him from the rest of us.” He rarely socialized with coworkers, lived alone in his Harlem apartment, and maintained strict boundaries between his professional and personal lives. Family members described “numerous attractive lady friends,” suggesting Baker performed different identities for different audiences — a survival strategy familiar to many closeted individuals of his era.

Despite these barriers, colleagues universally described Baker as a gentleman. Jerry Iger praised his professionalism, Ruth Roche became his steadfast advocate and collaborator, and Arnold Drake declared: “Matt Baker was one of the first important artists in comics. Not one of the first important black artists, one of the first important artists, period.”

Racing alone in a segregated field

Baker’s success becomes even more remarkable when contextualized within the broader landscape of Black Golden Age creators. Jackie Ormes, the first African-American woman cartoonist, could only publish in Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier despite her extraordinary talent. When entrepreneur Orrin C. Evans tried to publish a second issue of “All-Negro Comics” in 1947, every paper supplier refused to sell to him — almost certainly due to racial sabotage. Alvin Hollingsworth, who started in comics at age 12, eventually abandoned the medium entirely for fine art and academia.

Legal segregation prevented Black creators from working in mainstream studios until 1957. Publishers deliberately hid Black artists’ racial identities to avoid Southern boycotts. When Black characters appeared in mainstream comics, they were depicted as “brutal savages, devious witch doctors, or unintelligible minstrels.” Much of Baker’s early work was inked over by white artists who received the credit. Yet Baker achieved something his contemporaries couldn’t: consistent work for major publishers including Fox, Fiction House, Quality, St. John, and eventually Atlas/Marvel.

His strategy mirrored Jackie Robinson’s in baseball — be so exceptionally talented that exclusion becomes impossible. But unlike Robinson, who became a civil rights symbol, Baker remained publicly silent about race. He created Voodah, the first Black superhero, only to watch publishers recolor the character white. He let his talent speak rather than his voice, focusing on professional excellence over explicit activism. This pragmatism enabled his survival but contributed to his historical invisibility.

The restoration of a reputation

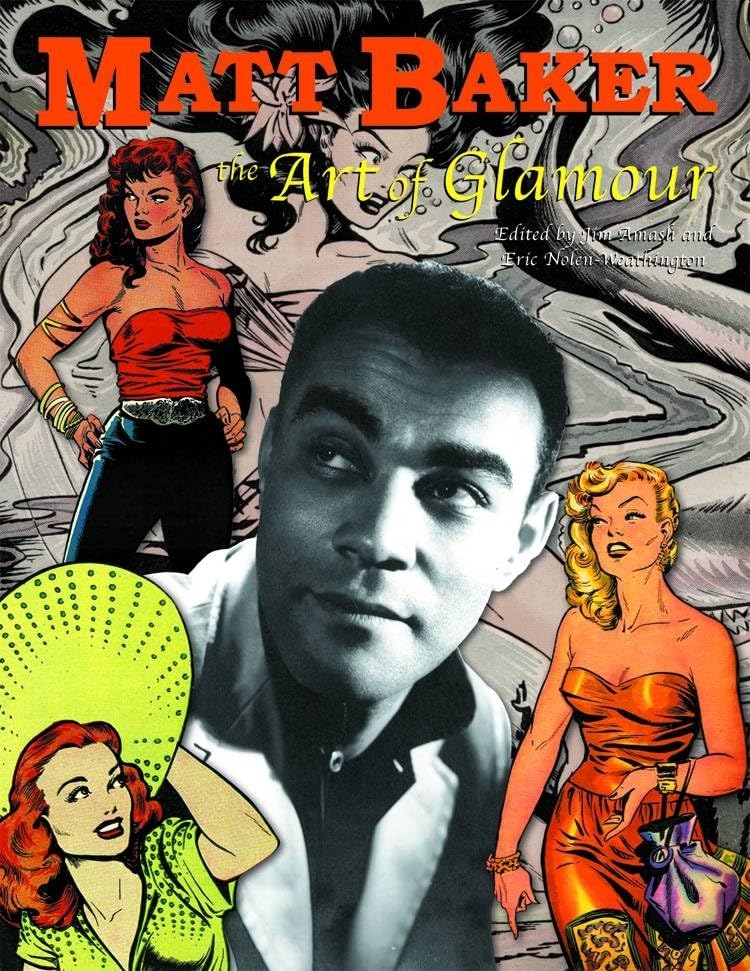

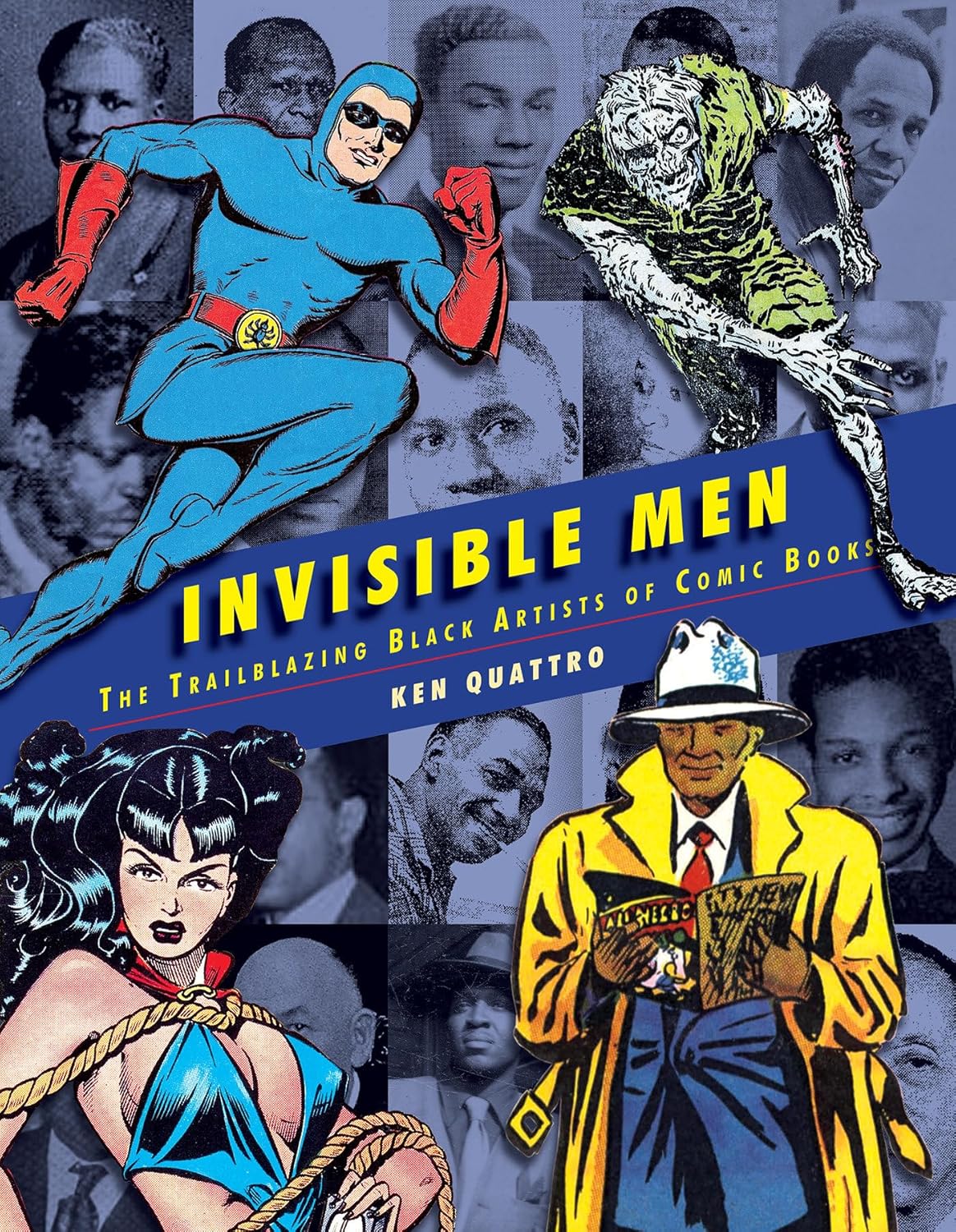

The modern reclamation of Baker’s legacy began with Jim Amash and Eric Nolen-Weathington’s 2012 book “Matt Baker: The Art of Glamour,” featuring interviews with colleagues and family alongside restored artwork. But the breakthrough came with Ken Quattro’s “Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books” (2021), which positioned Baker as the centerpiece among 18 forgotten Black Golden Age creators. Quattro spent 15 years researching primary sources from Black newspapers and magazines, finally providing the documentation Baker’s legacy deserved.

Heritage Auctions now regularly holds Matt Baker showcases — a CGC 9.6 copy of Phantom Lady #17 recently sold for $700,000, while even poor-condition copies command $12,000. Contemporary scholars like Monalesia Earle are uncovering the sophisticated techniques hidden in his work. The Comics Journal, SYFY Wire, and academic journals now feature Baker retrospectives. His influence on modern artists from Dave Stevens to Adam Hughes is finally acknowledged.

Yet questions remain about what Baker might have achieved with more time. His heart, damaged in childhood, gave him just 37 years. In that brief span, he created over 1,000 pages of sequential art, pioneered the graphic novel format, designed one of comics’ most iconic characters, created the medium’s first Black superhero, and established artistic techniques still studied today. He did this while navigating the triple marginalization of being Black, gay, and working in a disreputable medium, maintaining his dignity through impeccable dress and exceptional talent.

The genius who drew the future

Matt Baker’s story isn’t just about overcoming barriers — it’s about how American culture systematically erases its most innovative voices when they don’t fit preferred narratives. A Black gay man created the artistic template for how women would be depicted in comics for generations. His work was literally presented to Congress as evidence of comics’ cultural power. He pioneered the graphic novel format decades before the term existed. Yet for fifty years, his name appeared in no histories, no hall of fame, no retrospectives.

The recent restoration of Baker’s reputation reveals how many other Matt Bakers might exist — artists whose contributions were erased because of who they were rather than what they created. Ken Quattro found 18 other forgotten Black Golden Age creators in his research, each with their own stories of excellence despite exclusion. Baker succeeded not by challenging the system directly but by being undeniably excellent within it, letting his pencil speak truths his voice couldn’t safely express.

Today, when a Phantom Lady #17 sells for three-quarters of a million dollars, when contemporary artists cite Baker as foundational, when scholars decode the sophisticated rebellion hidden in his panel layouts, we glimpse what was nearly lost. Matt Baker drew the future of American comics while being written out of its history. His restoration reminds us that genius persists despite erasure, that art transcends the prejudices of its time, and that sometimes the most revolutionary act is simply refusing to disappear.

Books:

Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matt_Baker_(artist)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/It_Rhymes_with_Lust

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phantom_Lady

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dave_Stevens

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Hughes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seduction_of_the_Innocent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Senate_Subcommittee_on_Juvenile_Delinquency

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrayal_of_black_people_in_comics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jackie_Ormes

Historical & Educational Resources:

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/baker-clarence-matthew-1921-1959/

https://greatblackheroes.com/entertainment/matt-baker/

https://cbldf.org/2016/02/profiles-in-black-cartooning-matt-baker/

https://libwww.freelibrary.org/blog/post/4831

https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/10/the-senate-comic-book-hearings-of-1954/

https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6542/

Comics Industry Sites:

https://www.cgccomics.com/news/article/13082/matt-baker-phantom-lady-seven-seas/

https://www.cgccomics.com/news/article/11937/matt-baker-heritage/

https://comics.ha.com/comic-artist-index/matt-baker.s?id=500202052

https://www.keycollectorcomics.com/issue/phantom-lady-1-17,30600/

https://gocollect.com/blog/key-creator-matt-baker

https://comicartcommunity.com/gallery/categories.php?cat_id=25

News & Magazine Articles:

https://www.syfy.com/syfy-wire/ken-quattro-black-comic-artists-history-invisible-men

https://www.ocregister.com/2021/01/14/how-a-15-year-quest-to-find-the-work-of-black-comic-book-artists-became-invisible-men/

https://www.yesweekly.com/news/piedmont-born-comic-book-pioneer-matt-baker/article_5c1e1488-ea15-5715-b2ce-b0d17fb09416.html

https://www.detroitpbs.org/news-media/one-detroit/one-detroit-ken-quattro-discusses-comic-artist-book-invisible-men/

https://www.cbr.com/scotts-classic-comics-corner-spotlight-on-alvin-a-c-hollingsworth/

https://tripwiremagazine.co.uk/headlines/tripwires-101-greatest-comic-artists-of-all-time-no-43-adam-hughes/

Blog & Community Sites:

https://museumofuncutfunk.com/2012/11/07/matt-baker-first-black-comic-artist/

https://thewholeartnebula.com/2023/07/23/matt-baker-kind-of-a-big-deal/

https://thepatronsaintofsuperheroes.wordpress.com/2023/04/10/mike-grellstyroc-vs-matt-bakers-phantom-lady/

https://thepatronsaintofsuperheroes.wordpress.com/2017/01/02/black-in-the-golden-age/

https://blackcomixuniverse.com/project/phantom-lady-17-illustrated-by-matt-baker/

http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.com/2013/12/matt-baker-making-most-of-it.html

http://johnrozum.blogspot.com/2010/08/arnold-drake.html

https://gocomics.typepad.com/rcharvey/2013/02/matt-baker-the-art-of-glamour.html

https://picturingamerica142762412.wordpress.com/comic-books/

https://community.oerproject.com/b/blog/posts/a-serious-history-of-black-comics-creators

Reference & Academic:

https://www.lambiek.net/artists/b/baker_matt.htm

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43737440

https://www.philipac.com/my-noose-around-that-prettys-neck

https://www.rutgersuniversitypress.org/desegregating-comics/9781978825017/

Books on Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/Matt-Baker-Glamour-Jim-Amash/dp/1605490326

https://www.amazon.com/Invisible-Men-Artists-Golden-Comics/dp/1684055865

Other:

https://www.budsartbooks.com/product/matt-baker-the-art-of-glamour/

https://geekfrontiers.com/matt-baker-a-golden-age-legend/