La Matanza: Texas’s Suppressed Decade of Racial Terror (1910-1920)

Between 1910 and 1920, Texas Rangers and vigilantes systematically killed between 300 and 5,000 Mexican Americans along the Texas-Mexico border in one of the worst periods of state-sanctioned racial violence in U.S. history. Known as La Matanza (“The Massacre”) or Hora de Sangre (“Hour of Blood”), this decade of terror involved mass executions without trial, torture, and the deliberate display of corpses to terrorize entire communities. The violence was so systematic that a San Antonio newspaper stopped reporting Mexican deaths because they had become “too common to be news.” For over a century, Texas suppressed this history by sealing investigation transcripts, excluding it from textbooks, and promoting the mythology of heroic Texas Rangers while the affected border counties became the poorest in the state—a legacy of trauma and dispossession that persists today.

The Machinery of Mass Violence

The scale of killing during La Matanza defies precise documentation because the perpetrators deliberately destroyed records and left bodies to decompose in remote areas. Historians estimate the death toll ranges from 300 documented victims to potentially 5,000 killed, with the wide variation reflecting both the systematic nature of the violence and efforts to conceal it. The violence peaked between August 1915 and June 1916, when an estimated 100-300 murders occurred in South Texas alone. Archaeological investigations at massacre sites continue revealing new evidence—at Porvenir, researchers in 2015 recovered 27 artifacts including bullets with embedded human bone fragments, confirming execution-style killings by at least 9-10 shooters using military ammunition.

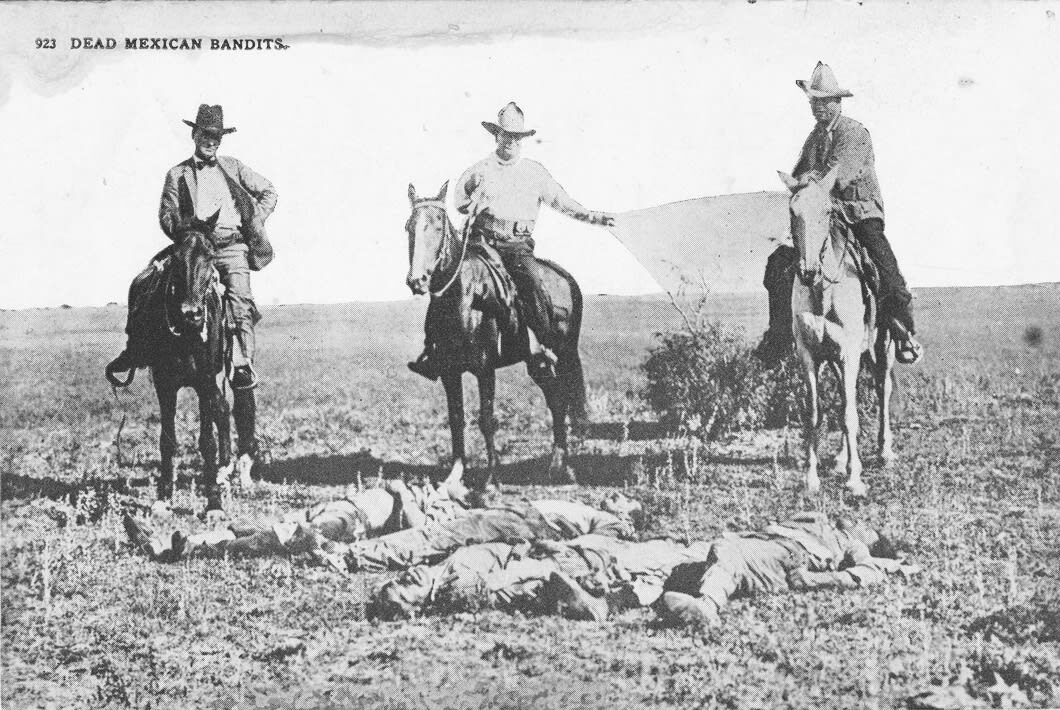

The methods of violence reflected a deliberate campaign of terror designed to drive Mexican Americans from their lands. Rangers and vigilantes conducted mass hangings from trees and telephone poles, leaving bodies dangling for weeks. They burned victims alive, as with 20-year-old Antonio Rodriguez in November 1910, who was doused with gasoline and set on fire by a Rocksprings mob. Bodies were routinely left to rot in the sun as warnings, with Rangers like Captain Henry Ransom ordering that corpses remain untouched “to spread fear.” The violence became so normalized that Rangers posed with lynched bodies for souvenir postcards, distributed throughout early 20th century Texas.

The Porvenir Massacre of January 28, 1918 exemplifies the systematic nature of these killings. Texas Rangers Company B, led by Captain James Monroe Fox, joined eight U.S. Cavalry soldiers and four local ranchers in surrounding the village at dawn. They separated 15 men and boys aged 16 to 72 from their families, marched them to a nearby bluff, and executed them by firing squad at close range—ballistic evidence shows victims were shot from as close as three feet away. The victims included Manuel Moralez, 47, who owned 1,600 acres and whose sixth child was born that night; Roman Nieves, 48, who owned 320 acres; and Tiburcio Jáques, father-in-law of the local schoolteacher. The next day, the U.S. Army burned Porvenir to the ground, forcing 140 survivors to flee to Mexico.

Los Diablos Tejanos: The Rangers as Instruments of Terror

The Texas Rangers functioned as the primary instruments of state-sanctioned racial violence during La Matanza, earning the name “los diablos tejanos” (the Texas devils) from terrorized Mexican communities. This reputation for brutality predated the 1910s—during the Mexican-American War, General Zachary Taylor stated there was “scarcely a form of crime that has not been reported to me as committed by them.” By the early 20th century, the Rangers had evolved into what scholar Monica Muñoz Martinez calls “a state-sponsored terror squad directed to secure white racial hegemony along the Texas-Mexico border.”

The Rangers operated with complete legal impunity, their numbers expanding from 13 members in 1913 to over 1,000 by 1918 through the creation of “Special Rangers” and “Loyalty Rangers.” Governor James Ferguson explicitly authorized this expansion, while Governor Oscar Colquitt instructed Rangers to kill Mexican raiders “at the risk of their lives.” Rangers routinely employed “la ley de fuga” (law of flight)—killing prisoners while claiming they were trying to escape. Even military officers became alarmed, with General Frederick Funston threatening martial law to restrain Ranger violence.

Specific Rangers emerged as notorious perpetrators whose names survive in survivor testimonies. Captain A.Y. Baker instigated the September 1915 mass hanging near Ebenezer, where Rangers hanged approximately 12 captured raiders from trees. A National Guard soldier witnessed Baker “killing three guys, three Mexican fellows in cold blood… He was killing Mexicans on sight.” Frank Hamer, later mythologized for killing Bonnie and Clyde, physically threatened State Representative José Tomás Canales in December 1918 for investigating Ranger abuses, stalking him at the state capitol and telling him to “stop monkeying with the Rangers.”

Captain Henry Ransom exemplified the casual brutality of Ranger operations. On September 27, 1915, prominent landowners Jesús Bazán and Antonio Longoria rode to report stolen horses to Rangers at the Sam Lane ranch. Ransom followed them in a Ford Model T and, without warning, shot both men in the back as they rode their horses. He left their bodies on the road for two days, with 19-year-old Anglo cowboy Roland Warnock later testifying: “There were so many innocent people killed in that mess that it just made you sick to your heart.”

Revolution, Rebellion, and Manufactured Threats

The Mexican Revolution beginning in 1910 created genuine instability along the border but was cynically exploited to justify disproportionate violence against all Mexican Americans. Nearly one-tenth of Mexico’s population fled to the United States during the revolution, tripling the Mexican population in Texas. While revolutionary factions did use the border region as a staging ground, the actual threat was vastly exaggerated—border raids resulted in approximately 21 American deaths, yet were used to justify killing hundreds or thousands of Mexican Americans.

The Plan de San Diego of 1915 became the primary justification for La Matanza’s bloodiest phase. This document, drafted in a Texas prison, called for an armed uprising to “liberate” Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Colorado, proposing to execute all Anglo males over 16. Despite extremely limited implementation—only about 30 raids occurred between July 1915 and July 1916—the Plan was used to justify collective punishment against entire Mexican American communities. Evidence suggests the Plan may have been manipulated by various factions including Venustiano Carranza’s government and German agents seeking to distract the U.S. from World War I.

The border militarization that followed created conditions normalizing violence. President Wilson deployed 110,000-135,000 National Guard troops by June 1916, with an additional 35,000 U.S. Army troops stationed along the Texas border by 1917. This massive military presence, far exceeding any actual threat, created a war zone atmosphere where Mexican Americans were treated as enemy combatants. The deployment legitimized treating the border as an active battlefield, with soldiers and Rangers operating under rules of engagement that assumed Mexican Americans were potential enemies.

Economic factors drove much of the violence, representing one of the largest land transfers in Texas history. New railroad connections in the early 20th century dramatically increased land values, creating incentives for Anglo settlers to seize Mexican-owned properties. As one Laredo newspaper observed in 1910: “The lands which mainly belonged to Mexicans pass to the hands of Americans… the old proprietors work as laborers on the same lands that used to belong to them.” The violence served dual purposes—terrorizing Mexican Americans into fleeing while clearing land titles for Anglo development. The “Great Exodus” saw approximately 50,000 Mexican Americans flee to Mexico, abandoning property and cattle that were subsequently claimed by Anglo settlers.

José Tomás Canales: A Legislator Confronts State Terror

In 1919, State Representative José Tomás Canales launched the first and only official investigation into La Matanza, risking his life to expose Ranger violence. Canales, the only Hispanic member of the Texas Legislature, came from a prominent ranching family and owned 30,000 acres—his privileged position made his stand particularly significant. After constituents brought forward numerous allegations of Ranger misconduct, including the Porvenir Massacre, Canales filed 19 formal charges against the Rangers and introduced House Bill 5 to reform the force.

The bill proposed reducing Rangers to 24 men in peacetime, requiring two years prior law enforcement experience, mandating surety bonds for civil liability, and establishing local oversight. The proposal triggered immediate retaliation. On December 11, 1918, Frank Hamer physically threatened Canales in Brownsville, telling him to “stop monkeying with the Rangers.” When Canales reported this to Governor William Hobby, Hamer was merely required to apologize but continued stalking Canales at the state capitol. The threats were credible enough that Sam Johnson, Lyndon B. Johnson’s father, and other sympathetic legislators escorted Canales to the hearings as protection.

The Joint Committee investigation from January 31 to February 13, 1919, heard testimony from 83 witnesses over two weeks, producing over 1,600 pages of transcript. Witnesses documented mass executions, torture, and systematic abuse. Judge James B. Wells testified about discovering 11 Mexican corpses in advanced decay. Rosenda Mega, a Porvenir survivor, testified that Rangers “took them about one-quarter of a mile…and then in a very cowardly manner, and without examining any of them, shot them.” The committee acknowledged Rangers were “guilty of, and are responsible for, the gross violation of both civil and criminal laws.”

Despite overwhelming evidence, the investigation was systematically undermined. Rangers’ attorneys attacked Canales’ mental health, claiming he suffered “delusions,” and questioned his loyalty based on his Mexican ancestry, stating “blood is thicker than water.” The House voted to seal the transcripts, which remained inaccessible for over 50 years until parts were discovered in the National Archives in 1975. Chairman Bledsoe’s amended version of House Bill 5 was so weakened that Canales voted against his own bill. The Rangers were reduced only from 89 to 75 members, with no surety bonds or local oversight required. No Rangers were ever prosecuted, though 45 “undesirable characters” were dismissed and Company B was disbanded. Canales, fearing for his life, did not seek re-election in 1920.

The Human Cost: Victims and Their Silenced Stories

Behind the statistics lie individual tragedies that decimated families and communities. Jesús Bazán, 67, and his son-in-law Antonio Longoria, 49, were prominent Tejano landowners who faced an impossible choice when raiders stole their horses—report the theft and risk retaliation, or stay silent and be accused of supporting “bandits.” Their decision to report to Rangers cost them their lives when Captain Ransom shot them in the back. Bazán’s widow Epigmenia never claimed the bodies out of fear, and the family lost their wealth and influence.

Paulino Serda, a small ranch owner near Edinburg, was forced at gunpoint to let Mexican bandits pass through his property. When Rangers learned of this, they came to “question” him privately. His wife heard gunshots during the interrogation—both Paulino and his father Donanciano were killed the same day, leaving a widow with young children including a one-year-old daughter. The family abandoned their ranch and moved to town to restart their lives.

Survivors carried trauma for generations. Juan Bonilla Flores, 12 years old during the Porvenir Massacre, discovered his father Longino’s body among the 15 executed men. He spent his life preserving the memory, finally recording his testimony in 2002. Roland Warnock, the Anglo cowboy who witnessed the Bazán-Longoria murders, created a documentary with his grandson in 2004, saying the killings “made you sick to your heart to see it happening.”

Mexican American families preserved these memories through corridos (ballads) and oral histories despite official silence. Songs like “El Corrido de los Rangers” documented state violence from the victims’ perspective, serving as “newspapers for the oppressed.” Families like the Coodys and Martinez descendants spent lifetimes researching and advocating for recognition. Ricardo Martínez grew up knowing his grandfather and great-grandfather were murdered together but was told they were “mistaken for bandits”—only later learning the truth about their execution for reporting a crime.

A Century of Deliberate Erasure

Texas systematically suppressed La Matanza history through institutional mechanisms that created historical amnesia lasting generations. The 1919 Canales investigation transcripts, containing 1,600 pages of testimony documenting state-sanctioned murder, were sealed by House vote and remained inaccessible until historian Jim Sandos discovered portions in the National Archives in 1975—56 years later. Historian Walter Prescott Webb, given privileged access to the sealed documents, used them to write his influential 1935 book “The Texas Rangers,” which defended Ranger violence and shaped public perception for decades.

Educational institutions excluded La Matanza from curricula throughout the 20th century. As late as 2021, descendants noted “there are adults now that don’t know the story, let alone children.” Texas history textbooks followed “Lost Cause” patterns that romanticized Rangers as frontier heroes while erasing their role in racial violence. Universities and historical associations avoided funding research into anti-Mexican violence, while museums excluded these narratives from Texas history exhibitions.

The media participated in suppression through both action and inaction. By 1915, San Antonio newspapers stopped reporting Mexican deaths because they had become “so common it is not news anymore.” When deaths were reported, passive voice construction obscured perpetrators—”Mexicans were found dead” rather than “Rangers killed Mexicans.” Official records were destroyed or never created, with many killings going uninvestigated. No Texas Rangers were ever prosecuted for their involvement in massacres, establishing a pattern of impunity that persisted for generations.

Despite institutional suppression, Mexican American families maintained collective memory through multi-generational storytelling. Melba Coody spent her entire life sharing her great-grandfather Jesús Bazán’s story “with anyone who would listen.” Corridos preserved names of victims and documented violence when official records wouldn’t. Families maintained knowledge of specific details across generations—dates, locations, and circumstances of deaths—even when the broader public narrative denied these events occurred.

Breaking the Silence: The Fight for Recognition

The “Refusing to Forget” movement, founded in 2014 by historians Monica Muñoz Martinez, Trinidad Gonzales, Sonia Hernández, and Benjamin Johnson, launched the first systematic effort to recover La Matanza history. The movement’s name itself challenges a century of enforced amnesia. Working with descendant communities, they created digital archives, documented family histories, and connected historical violence to contemporary border issues. Their efforts earned the 2021 Organization of American Historians “Friend of History Award” and transformed public understanding of Texas history.

The campaign for historical markers revealed continuing institutional resistance. The Texas Historical Commission rejected applications in 2014 and 2015 for markers commemorating the Bazán-Longoria murders, questioning the “urgency for more markers on the same historical subject.” Only after sustained pressure did the commission approve four markers between 2017-2019. The November 3, 2018 dedication of the Bazán-Longoria marker drew over 130 attendees including descendants who had waited generations for recognition.

Museum exhibitions brought visual evidence of atrocities to public consciousness. The 2016 “Life and Death on the Border: 1910-1920” exhibit at Austin’s Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum displayed photographs of Rangers posing with lynching victims—images that had circulated as postcards a century earlier. The exhibit’s 2024 arrival at the Houston Holocaust Museum explicitly connected La Matanza to other genocidal violence, challenging narratives of American exceptionalism.

Academic recovery projects have documented at least 109 verified victims while acknowledging hundreds or thousands more remain unnamed. South Texas College compiled victim databases, oral history projects like “Historias de la Gente” collected community memories, and books like Martinez’s “The Injustice Never Leaves You” (2018) provided scholarly documentation of state terrorism. Archaeological investigations at sites like Porvenir continue revealing physical evidence of massacres, with bullet fragments and human remains confirming survivor testimonies dismissed for a century.

The Violence That Never Ended

La Matanza’s impacts persist in measurable ways across South Texas. The border counties where violence occurred remain among Texas’s poorest, with over 29 million people living in colonias—settlements lacking basic infrastructure like running water and electricity. This geographic correlation between historical violence and contemporary poverty reflects systematic dispossession that was never remedied. Families lost hundreds of thousands of acres and millions in property value, creating intergenerational poverty that persists today.

Research documents how “The Legacy of La Matanza, Intergenerational Trauma” continues affecting descendant communities through “emotional and psychological wounding transmitted across generations.” Families report ongoing impacts from ancestors’ experiences of state violence—difficulty trusting authorities, reluctance to report crimes, and persistent fear of deportation regardless of citizenship status. The violence disrupted traditional leadership structures and community networks that were never fully rebuilt.

La Matanza established patterns of state violence that echo in contemporary border enforcement. The 2019 El Paso massacre, occurring 90 miles from Porvenir, saw a gunman target Mexicans using rhetoric eerily similar to 1910s “invasion” language. Texas Senate Bill 4 (2023), making illegal border crossing a state crime, follows legal frameworks established during La Matanza. Current border militarization—walls, surveillance, armed patrols—mirrors the massive military deployment of 1916-1917 that normalized treating Mexican Americans as enemies.

The systematic segregation following La Matanza created what scholars term “Juan Crow” laws—a parallel system to Jim Crow targeting Mexican Americans. Despite legal classification as “white,” Mexican Americans faced systematic exclusion from schools, businesses, and public accommodations. Signs reading “No Dogs or Mexicans Allowed” appeared throughout Texas. Educational segregation confined Mexican American children to inferior “Mexican schools,” while employment discrimination restricted them to agricultural and manual labor. This segregation, enforced through violence and intimidation like Jim Crow, created lasting disparities in education, wealth, and political power.

Conclusion

La Matanza represents American state terrorism on a scale that challenges fundamental narratives about law, order, and justice in the United States. For a decade, Texas Rangers and vigilantes systematically murdered Mexican Americans with full state sanction, transforming the border into a killing field where displaying corpses became standard procedure and newspapers stopped counting the dead. The violence served explicit economic and racial purposes—transferring land from Mexican to Anglo ownership while establishing white supremacy through terror.

The century-long suppression of this history through sealed transcripts, educational exclusion, and institutional resistance reveals how powerful interests can erase mass atrocities from collective memory. That it took until 2018 for Texas to acknowledge with a historical marker that two prominent citizens were murdered by Rangers for reporting a crime demonstrates the depth of this suppression. The “Refusing to Forget” movement’s success in recovering this history proves both the resilience of community memory and the importance of challenging official narratives.

Understanding La Matanza is essential for comprehending contemporary border dynamics. The poorest counties in Texas trace their poverty to this period of dispossession. Current immigration enforcement echoes century-old patterns of collective punishment and racial profiling. The intergenerational trauma documented in descendant communities shapes political participation, economic opportunity, and relationships with law enforcement today. As one descendant noted after the 2019 El Paso shooting, those who refuse to acknowledge history ensure its repetition.

The recovery of La Matanza history remains incomplete—most victims remain unnamed, most perpetrators unidentified, most stories untold. But the transformation from suppressed history to public recognition, however partial, demonstrates that state terrorism cannot be permanently erased when communities preserve memory across generations. La Matanza stands as both a warning about state capacity for racial violence and testament to the endurance of those who refuse to forget.

Works cited

La Matanza – UTRGV Digital Exhibits, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://omeka.utrgv.edu/items/show/1663

La Matanza (1910–1920) – Wikipedia, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Matanza_(1910%E2%80%931920)

Ninth Day of Canales Hearings – Refusing to Forget, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://refusingtoforget.org/ninth-day-of-canales-hearings/

CRITICAL REMEMBERING: AMPLIFYING, ANALYZING, AND …, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://journals.law.harvard.edu/lalr/wp-content/uploads/sites/85/2023/07/HLA102.pdf

en.wikipedia.org, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Matanza_(1910%E2%80%931920)#:~:text=Ranger%20violence%20reached%20its%20peak,Mexico%20to%20escape%20the%20violence.

History of Latinos in Texas – Jolt Action, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://jolttx.org/history-of-latinos-in-texas/

Details – Matanza of 1915 – Atlas Number 5507018128 – Atlas: Texas Historical Commission, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://atlas.thc.texas.gov/Details/5507018128/print

Reconstruction era – Wikipedia, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstruction_era

Terror to Overturn Reconstruction Era Advances – Zinn Education Project, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.zinnedproject.org/collection/terror-to-overturn-reconstruction/

Mass racial violence in the United States – Wikipedia, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_racial_violence_in_the_United_States

Life and Death on the Border 1910-1920 | Bullock Texas State History Museum, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.thestoryoftexas.com/visit/exhibits/life-and-death-on-the-border-1910-1920

The History – Refusing to Forget, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://refusingtoforget.org/the-history/

Civil Rights – Texas State Historical Association, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/civil-rights

Land Loss in Trying Times | Mexican | Immigration and Relocation in …, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/mexican/land-loss-in-trying-times/

History of Mexican Americans – Wikipedia, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Mexican_Americans

La Matanza 1915: Racial Violence in Rio Grande Valley – Trucha RGV, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://truchargv.com/rio-grande-valley-la-matanza/

Porvenir: The Quiet Massacre – Sul Ross State University, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.sulross.edu/porvenir-the-quiet-massacre/

The Texas Rangers Killed Hundreds of Hispanic Americans During …, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.texasstandard.org/stories/texas-exhibit-refuses-to-forget-one-of-the-worst-periods-of-state-sanctioned-violence/

The Texas Ranger Story | Texas State History Museum, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.thestoryoftexas.com/discover/campfire-stories/texas-ranger

Harry Warren’s Porvenir Notebook | Bullock Texas State History Museum, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.thestoryoftexas.com/discover/artifacts/harry-warren-porvenir-notebook-spotlight-1-1-19

Black Texas Ranger History, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.texasranger.org/Pages/History/Black-Rangers

New research quantifies effects of lynchings of Mexicans and Mexican Americans on the wider community | Colorado Arts and Sciences Magazine, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2024/09/20/new-research-quantifies-effects-lynchings-mexicans-and-mexican-americans-wider-community

Joint Committee of the Senate and the House in the Investigation of …, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/joint-committee-of-the-senate-and-the-house-in-the-investigation-of-the-texas-state-ranger-force-canales-investigation

José T. Canales, Conflict and Compromise, Tejano Identity in …, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.tsl.texas.gov/sites/default/files/public/tslac/arc/thrab/2018liraramirez.pdf

Canales Reform HB 5 – Refusing to Forget, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://refusingtoforget.org/canales-reform-hb-5/

1919 Texas Rangers Investigation Report – San Antonio Review – Pressbooks.pub, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://pressbooks.pub/sarv/chapter/excerpt-from-volume-3-of-the-1919-texas-rangers-investigation-report/

Biography: Jovita Idar – National Women’s History Museum, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/jovita-idar

Jovita Idar – Refusing to Forget, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://refusingtoforget.org/historical-markers/jovita-idar/

Latino Civil Rights Timeline, 1903 to 2006 | Learning for Justice, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/classroom-resources/lessons/latino-civil-rights-timeline-1903-to-2006

Texas Rangers’ history of violence toward people of color often …, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://www.texastribune.org/2020/08/15/texas-rangers-racist-violent-history/

Refusing to Forget – Not Even Past, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://notevenpast.org/refusing-to-forget/

Refusing to Forget: Home, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://refusingtoforget.org/

1910 – 1920: Life & Death on the Border – Library | South Texas College Library, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://library.southtexascollege.edu/1910-1920-life-death-on-the-border/

Life & Death on the Border 1910-1920 – Library | South Texas College Library, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://library.southtexascollege.edu/life-death-on-the-border-1910-1920/

Historical Markers – Refusing to Forget, accessed on September 12, 2025, https://refusingtoforget.org/historical-markers/