I. Prologue: The Shadow of Jim Crow and the Rise of the Boxer

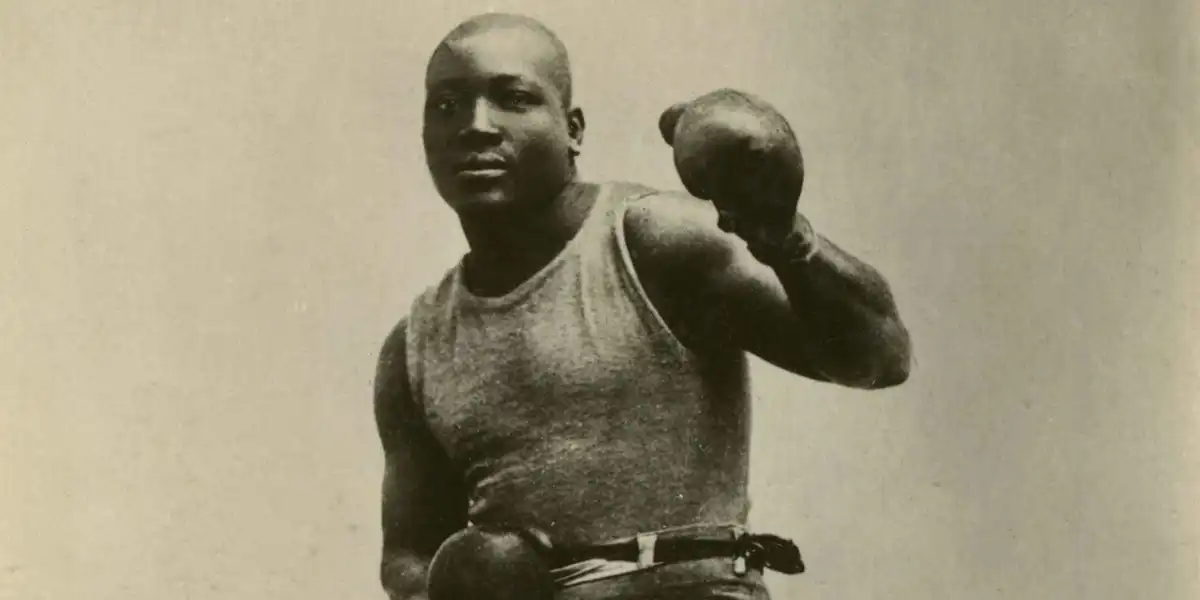

The life and career of Arthur John Johnson, known universally as Jack Johnson, represent one of the most profound and catalytic challenges to American white supremacy during the Jim Crow era. Born in the immediate aftermath of Reconstruction, Johnson leveraged the brutal structure of segregated boxing to achieve global fame, thereby violating nearly every prevailing social and legal norm designed to constrain African Americans.

I.A. The Galveston Origin (1878–1890s)

Arthur John Johnson was born on March 31, 1878, in Galveston, Texas. His birth occurred the year following the collapse of Reconstruction, a period that saw Southern states rapidly erect systemic barriers of racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Johnson’s parents, Henry and Tina (“Tiny”), were former slaves who established a degree of stability for their family. Henry worked as a school janitor, and Tina was a laundress. They successfully managed to purchase their own residence at 808 Broadway, located in Galveston’s racially mixed Twelfth Ward.

Jack, who later reversed the order of his given names, was the third of nine children, five of whom reached adulthood. His parents ensured that all their children received at least five years of education. Although a black high school was available to him, Johnson did not attend. Instead, he left school early to enter the workforce and help provide financial support for his large family. His early jobs included sweeping a barbershop, working as a porter in a gambling parlor, and assisting a baker. This decision to prioritize labor over formal education was not due to a lack of intellectual capacity but was rooted in economic necessity, a pattern that would define his pursuit of wealth as a form of armor against racial oppression.

Johnson’s youth in the Twelfth Ward exposed him to an environment less rigidly segregated than the Deep South. He was reportedly part of the racially mixed 11th Street and Avenue K gang. This early exposure to racial fluidity may have contributed to his later, defiant disregard for the rigid racial lines enforced elsewhere in society, particularly concerning his social status and personal relationships.

I.B. Apprenticeship and the Colored Circuit

Johnson’s introduction to prizefighting was a pragmatic outgrowth of his search for sustainable work. While apprenticing to paint carriages in Dallas, the shop owner, Walter Lewis, introduced him to the sport. Johnson later claimed in his 1927 autobiography that he had avoided fighting until he was twelve years old. His first documented fight took place in the summer of 1895 on the beach against fellow dockworker John Lee, which Johnson won, earning a purse of $1.50.

Johnson quickly recognized the economic limitations of staying in Galveston, citing the “minimal” purses of $10, $15, or $20, which were often absorbed entirely by the wages of his seconds. This financial pragmatism motivated him to seek greater opportunities nationally and globally.

Johnson established his dominance within the segregated ranks of professional boxing. He took the unofficial World Colored Heavyweight Championship on February 5, 1903, by winning a twenty-round decision over Denver Ed Martin in Los Angeles. He successfully defended this distinction against the best available Black opponents for the next two years, defending the title 12 times in total, a number second only to the 26 defenses achieved by Harry Wills. During this period, he notably defeated future Colored Heavyweight Champions Sam McVey three times and Sam Langford once. Following his victory over the formidable Langford on points in a 15-rounder, Johnson strategically decided to never grant him another shot at the title, whether as the Colored Champion or later as the World Heavyweight Champion. This calculating approach highlighted his deep understanding of the boxing world’s economic structure: pursuing the highest financial prize—the World Heavyweight Championship, held exclusively by white boxers—was the sole path to genuine wealth and recognition, regardless of the quality of the opponent he bypassed within the Black circuit.

II. The World Heavyweight Crown and Global Recognition (1908-1910)

The ascension of Jack Johnson to the status of World Heavyweight Champion marked a pivotal moment in global race relations, transforming the sport into an explosive political theater.

II.A. Achieving the Zenith: The Tommy Burns Fight (1908)

Johnson tirelessly pursued the reigning champion, Tommy Burns, finally cornering him in Sydney, Australia, in 1908. Johnson secured a decisive victory, becoming the first Black World Heavyweight Champion.

This victory was immediately met with visceral and widespread racial animosity. The outrage was not limited to the United States but manifested globally, revealing the extent of the “Global Color Line”. In Australia, Johnson faced intense persecution; his brief affair with a young white woman resulted in her harassment, and Johnson was quickly made

persona non grata. Finding that opportunities to capitalize on his reputation and victory dried up due to the pervasive white hostility, Johnson was compelled to leave the country. This experience demonstrated clearly that the oppressive force of white supremacy was a worldwide phenomenon, reinforcing the systemic barriers that justified both colonial rule overseas and Jim Crow laws domestically.

II.B. The Manufacturing of the “Great White Hope”

Upon returning to the U.S. as the champion, Johnson became a figure of intense fear and hatred among the white majority. He flagrantly defied every prescribed racial convention of the era. Johnson was ostentatious, outspoken, and made no effort to conceal his wealth or his preferred relationships, as he exclusively dated and married white women. His very existence as a successful, defiant, wealthy Black man exposed the “profound racial divisions” embedded in American society, infuriating the establishment.

This societal panic led to the search for a savior—a white boxer who could physically and symbolically defeat Johnson and restore what was perceived as “collective racial prestige”. Writer Jack London popularized the term “Great White Hope” to describe the man tasked with this mission.

The established choice was James Jackson Jeffries, the former undefeated World Heavyweight Champion from 1899 to 1905, who had previously retired. Known for his enormous strength, durability, and his “crouching crab” defensive style, Jeffries was widely viewed as the only white man capable of reclaiming the title. Jeffries was ultimately coaxed out of retirement for this explicit racial crusade, transforming the impending bout from a sporting event into an existential battle for racial hierarchy. The expectation placed on Jeffries was monumental—he was tasked not merely with winning a fight but with redeeming the supposed superiority of the white race, an expectation that tragically set the stage for later racial violence.

III. The Fight of the Century (July 4, 1910): Victory and Cataclysm

The contest between Jack Johnson and James J. Jeffries, dubbed the “Fight of the Century,” remains one of the most culturally significant athletic events in American history, serving as a powerful social barometer of the country’s deepest prejudices.

III.A. Contextualizing the Conflict and the Bout

The bout was held on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada—a date that provided a “cruel irony” given the repressive wishes of the predominantly white audience. Johnson, following his custom, entered the ring first, appearing cool and confident. Jeffries’ entrance, however, signaled a massive roar from the crowd, elated to see their champion return to supposedly restore racial honor. Jeffries, having trimmed down to his original fighting weight, appeared intensely serious, wearing the weight of white America’s expectations. In a profound moment signaling the racial gravity of the contest, Jeffries refused to shake Johnson’s hand before the opening bell.

MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING

by William Waring Cuney

Oh, my Lord

What a morning,

Oh, my Lord,

What a feeling,

When Jack Johnson

Turned Jim Jeffries

Snow-white face

Up to the ceiling.

Yes, my Lord,

Fighting is wrong,

But what an uppercut.

Oh, my Lord,

What a morning,

Oh, my Lord

What a feeling,

When Jack Johnson

Turned Jim Jeffries

Lily-white face

Up to the ceiling.

Oh, my Lord

What a morning,

Oh, my Lord

Take care of Jack.

Keep him, Lord

As you made him,

Big, and strong, and black.

Johnson responded to Jeffries’s initial assaults with confidence and apparent ease, often smiling as the former champion attacked. Johnson’s boxing skill and power were overwhelming. He dominated the contest, systematically breaking down the retired champion. In the 15th round, Johnson secured victory by technical knockout, shattering the myth of white physical and athletic invincibility that Jeffries had been manufactured to represent. This victory was interpreted by white audiences across the United States not merely as an athletic loss but as a catastrophic defeat of white racial prestige, setting the stage for nationwide racial violence.

III.B. Professional Boxing Statistics (Harmonized Record)

While boxing statistics from the turn of the century often conflict due to incomplete record-keeping and varied rules regarding “No Decisions” (which could number up to 14 in some records) , the data confirms Johnson’s long and dominant career. Johnson’s career longevity and consistent success are highlighted by his overall record. Sources indicate a range of total professional fights from 94 to 113, with 79 recorded wins and 44 victories coming by knockout. He accumulated only 8 recorded losses and 12 draws, demonstrating exceptional resilience and skill over two decades.

Johnson’s command over the segregated circuit was undeniable, defending the World Colored Heavyweight Championship 12 times. After winning the ultimate prize, he continued to demonstrate his prowess on the world stage, defending the World Heavyweight title twice during his exile before losing it in 1915.

Johnson Professional Boxing Record Summary (Harmonized Data)

IV. The National Inferno: Detailed Analysis of the Post-Fight Riots

The triumph of Jack Johnson over James J. Jeffries on July 4, 1910, immediately triggered a catastrophic wave of racial violence across the United States. This civil unrest was not characterized by mutual disorder but by targeted attacks by white mobs against Black citizens who were celebrating the achievement.

IV.A. Mapping the Violence and Retaliation

Johnson’s victory provoked violent reactions in over 50 cities throughout the country. Historians regard the day as the single worst for race riots in American history until the unrest of the late 1960s. The core element of the violence was racial retribution: white mobs, enraged by the symbolic defeat of their “Hope,” attacked Black revelers.

The scale of the casualties and injuries was devastating, resulting in dozens of deaths and hundreds of injuries across the nation. In response to the assaults, Black individuals often resorted to self-defense, which resulted in several white people being stabbed or shot.

One of the most intense outbreaks occurred in Washington, D.C., where street mobs numbered as high as 7,000 people. In the violence there, white mobs attempted to lynch two Black men and succeeded in beating one Black man to death. The violence led to hundreds of injuries, including two white men who were stabbed to death by Black people acting in defense.

IV.B. Casualties, Arrests, and Disproportionate Retribution

The legal response that followed the violence was characterized by widespread arrests across the country. In Washington, D.C., authorities reported 236 arrests. The arrests, occurring amidst the violence often initiated by white mobs, demonstrate a crucial aspect of systemic injustice: Black individuals were penalized for either celebrating or defending themselves against attacks. The judicial system immediately acted to suppress the celebration of Johnson’s victory by punishing its beneficiaries, thereby utilizing law enforcement to reinforce the principles of white racial hierarchy that the boxing result had temporarily undermined.

The global reaction further underscores the fight’s political significance. Fearing that the image of a dominant Black champion would “inspire non-white peoples to rebel against white authority,” a “concerted effort throughout the British Empire” was made to ban the screening of the Jeffries-Johnson fight film. This act of censorship confirmed that the fight transcended sport, being viewed internationally as a political event capable of destabilizing European colonial control.

Summary of Key Casualties and Arrests in the 1910 Riots

Metric

Scope of Impact

Observed Outcome (Selected Examples)

Contextual Note

Cities Affected

Over 50 U.S. Cities

Widespread violence reported; D.C. mobs reached 7,000.

Violence recognized as the worst race riots until the 1960s.

Deaths

Dozens of Fatalities Nationwide

One Black man beaten to death; two white men stabbed to death in D.C..

Fatalities primarily resulted from white mob attacks and Black self-defense.

Injuries

Hundreds Injured Nationwide

Washington D.C.: At least 100 injuries reported.

Injuries were often the result of targeted assaults by white mobs on Black celebrants.

Arrests

Widespread Arrests

Washington D.C.: 236 people arrested.

Legal actions immediately followed, often suppressing Black citizens.

V. The Legal Weapon: Jack Johnson and the Mann Act

Following the failure of organized athletic attempts to defeat Johnson, the apparatus of the state mobilized legal mechanisms to neutralize him. Johnson’s Mann Act conviction stands as a primary historical example of how morality laws were deliberately employed as tools for racial control and political retaliation against disruptive Black figures.

V.A. The Mann Act and Racial Weaponization

The Mann Act, officially the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910, was ostensibly designed to combat human trafficking and prostitution. However, the law’s vague and broad interpretation allowed it to be weaponized for “political or social purposes,” specifically targeting Johnson due to his public defiance of Jim Crow racial norms, particularly his highly visible relationships with and marriages to white women.

The U.S. Department of Justice began investigating Johnson for potential violations almost immediately after the law was passed. This prolonged investigation, which lasted over two years, clearly indicated a concerted effort by federal authorities to find legal grounds to prosecute and imprison the world champion.

V.B. The Failed and Successful Indictments (1912-1913)

The first major attempt to prosecute Johnson occurred in October 1912. Johnson was arrested on state kidnapping charges and U.S. District Attorney James H. Wilkerson initiated a federal Mann Act case concerning Lucille Cameron. The case quickly collapsed when it became undeniable that Cameron was an adult and had been a prostitute before she met Johnson, undermining the central charge of illegal transportation for immoral purposes. In a final act of defiance against the prosecution, Johnson and Cameron were married in December 1912.

Assistant U.S. District Attorney Harry A. Parkin, determined to secure a conviction, was not deterred. He initiated an aggressive, “all-out effort” utilizing the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (the forerunner of the FBI) to scour the country for any other woman Johnson might have transported across state lines. Federal agents eventually traced Johnson’s former companion, Belle Schreiber, a known prostitute, to a whorehouse in Washington, D.C.. Schreiber’s detailed memory and her “bitterness at Johnson’s treatment of her” made her the ideal witness the investigators sought.

Using Schreiber’s testimony, the federal grand jury issued seven Mann Act indictments. In 1913, Johnson was convicted by an all-white jury for transporting Schreiber across state lines from Pittsburgh to Chicago. This conviction, secured under pressure and using testimony from a former partner, resulted in a sentence of a year and a day in prison. The process—the explicit mandate for an “all-out effort” followed by a guilty verdict delivered by an all-white jury—demonstrates that the legal system was being used as an explicit instrument of state retaliation against a prominent Black figure who refused to adhere to the rigid racial codes of the era. His true transgression was his social insubordination, and the conviction served as a judicial reinforcement of white supremacy.

Timeline of Major Legal Proceedings (Mann Act)

Date

Event Category

Key Figure/Witness

Significance

1910

Mann Act enacted

N/A

Law provided legal basis for targeted investigation of Johnson.

Oct/Nov 1912

Initial Arrests

Lucille Cameron

Law provided legal basis for targeted investigation of Johnson.

1913

Concerted Investigation

Assistant U.S. Attorney Harry A. Parkin

Mandated “all-out effort” to find evidence against Johnson.

1913

Trial and Conviction

Belle Schreiber (Prosecution Witness)

Convicted by an all-white jury; sentenced to one year and one day.

1913

Flight from Justice

N/A

Johnson fled the United States to avoid imprisonment.

VI. Exile and Ultimate Surrender (1913-1920)

Following his conviction, Johnson was sentenced to prison but immediately fled the country, initiating seven years of self-imposed exile.

VI.A. The Seven Years of Exile

After escaping, Johnson initially fled to Canada and then traveled extensively across Europe. He spent nearly a decade as a “rebel sojourner,” seeking a nation where he could live in peace and establish a career free from the bigotry that poisoned his professional and personal life in America. However, his experiences abroad confirmed the pervasive nature of the global color line, demonstrating that even international fame and wealth could not entirely protect him from systemic white supremacy.

During his exile, Johnson continued to box, defending his World Heavyweight title twice against challengers.

VI.B. The Loss of the Crown and Imprisonment

Johnson’s reign ultimately ended on April 5, 1915. He lost the championship to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. The 37-year-old champion was knocked out in the 26th round. The defeat became highly controversial, as persistent, though unproven, rumors suggested that Johnson deliberately threw the fight. This alleged concession was speculated to be part of a negotiation with U.S. authorities to secure his ability to return home and potentially receive a reduced sentence. This rumor highlights the agonizing psychological pressure Johnson faced, suggesting that even a figure defined by defiance may have felt compelled to trade his professional honor for the slim prospect of domestic freedom.

Johnson eventually chose to surrender to U.S. authorities. In 1920, he returned to the United States and served his sentence at the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. He was held for approximately 10 months and was documented as a “model prisoner” during his incarceration.

VII. Later Years, Legacy, and Historical Rectification

Jack Johnson continued to live a life characterized by entrepreneurship, showmanship, and a persistent struggle for economic solvency long after his boxing career waned and his prison sentence was served.

VII.A. Post-Boxing Ventures and Final Years

Johnson’s life following his release from Leavenworth in 1921 was an eclectic mix of attempts to leverage his fame and secure an income. His post-boxing career comprised a “cobbled-together string of jobs”. He engaged in various ventures, including running a restaurant, appearing in movies, fighting bulls and wrestlers in exhibitions, and giving lectures. Demonstrating a practical, inventive mind, he also patented a wrench. Furthermore, he published two memoirs and, at one point, even appeared with a flea circus. These endeavors reveal the financial difficulties and the persistent challenges he faced in finding stable opportunities within an American business and entertainment landscape still deeply resistant to a non-subservient Black man.

Jack Johnson died at the age of 68 in a car accident in 1946.

VII.B. Enduring Impact and Historical Rectification

Jack Johnson’s significance extends far beyond his athletic accomplishments. His success represented a seismic challenge to the racial hierarchy prevalent in the early 20th century. By breaking the color barrier in the sport’s most symbolic category, Johnson paved the way for future generations of African American athletes.

He was a profoundly polarizing figure. While he faced intense hostility from the white establishment and authorities, he was simultaneously celebrated by the Black community as a powerful symbol of defiance, success, and the transcendence of racial boundaries. His global recognition was substantial, with his victories inspiring people of color in countries where racial inequality was a pressing issue.

The history of Johnson’s persecution, particularly the Mann Act conviction, eventually led to decades of advocacy seeking historical justice. In 2018, Johnson was posthumously pardoned by U.S. President Donald Trump. The pardon explicitly acknowledged that Johnson had been convicted for what was widely considered a “racially motivated injustice”. This official rectification, occurring 72 years after his death, served as a crucial validation of the historical analysis that his conviction was not an act of legitimate criminal justice but a politically motivated attempt by the state to discipline and suppress a Black champion who dared to live outside the restrictive boundaries of Jim Crow.

Jack Johnson’s Legal and Historical Legacy Timeline

1878

Details:

Born in Galveston, TX.

Significance:

Born during the beginning of the Jim Crow era.

1908

Details:

Defeated Tommy Burns for World Heavyweight Title.

Significance:

Broke the color barrier in sports; triggered global white backlash.

1910

Details:

Defeated Jim Jeffries; nationwide race riots erupted.

Significance:

Victory catalyzed mass racial violence and social suppression.

1913

Details:

Convicted under the Mann Act for transporting Belle Schreiber.

Significance:

Legalized persecution based on race and defiance of social norms.

1913–1920

Details:

Lived in exile; lost title to Jess Willard (1915).

Significance:

Demonstrated the global reach of racial legal pressure.

1920

Details:

Served sentence at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

Significance:

Concluded the period of active persecution.

1946

Details:

Died in a car crash at age 68.

Significance:

End of his life, but his legacy continued to provoke controversy.

2018

Details:

Posthumously pardoned by President Donald Trump.

Significance:

Formal governmental acknowledgment of racial injustice.

VIII. Conclusion: The Legacy of Defiance

Jack Johnson was not just an athlete; he was a profound social irritant whose life laid bare the hypocrisy and violence inherent in Jim Crow America. His biography is a study in how success and defiance by a Black man could trigger systematic retribution—first via mass violence carried out by white mobs following his victory over the “Great White Hope,” and subsequently through the calculated, racially motivated application of federal law, embodied by the Mann Act prosecution. The relentless pursuit and eventual conviction of Johnson demonstrate that the state actively participated in reinforcing white racial supremacy where popular sentiment or physical force failed.

Johnson’s story remains central to the history of civil rights and sports, serving as an enduring testament to the obstacles faced by African American pioneers. By achieving and openly enjoying unprecedented wealth and public status, Johnson forced the United States to confront its own “unforgivable blackness,” challenging racial expectations in a manner that paved the way for future generations of defiant Black athletes.

Biographical Information

- Johnson’s Early Life | Unforgivable Blackness – PBS

- Jack Johnson (boxer) – Wikipedia

- Jack Johnson (boxer) – New World Encyclopedia

- Jack Johnson – BoxRec

- Jack Johnson Worksheets | Life, Boxing Career, Legacy – KidsKonnect

- Jack Johnson (1878–1946) | American Experience – PBS

Historical Context & Cultural Impact

- Historian explores overseas racial battles of iconic American boxer Jack Johnson – UB Reporter

- July 4, 1910: Johnson vs Jeffries – The Fight City

- Race War: The Fight of the Century – Counter Culture UK

- Johnson–Jeffries riots – Wikipedia

- James J. Jeffries – Wikipedia