I. Introduction: Contextualizing Necessity and Genesis

The Negro Motorist Green Book, often referred to simply as the Green Book, emerged not as a simple directory of amenities but as an indispensable tool for survival, mapping a clandestine network of safe havens necessary for African American travel across a racially hostile United States. Its existence chronicled a sophisticated, self-organized response to systemic racism, providing the infrastructure for mobility, commerce, and dignity during the Jim Crow era.

A. The Peril of the American Road: Jim Crow and Mobility

The Green Book was conceived and published during the Jim Crow era, which officially spanned the years 1936 to 1967, a period defined by widespread and often legally prescribed racial discrimination across the nation. For African American travelers, the act of road travel was fraught with extreme danger and inconvenience. Black motorists frequently faced refusal of service, denial of accommodation or food, and the humiliation of having to use segregated facilities or be served via the kitchen entrance. Beyond daily insults, travelers faced the severe dangers of arbitrary arrest, threats of physical violence, and, in severe cases, death—incidents that local authorities often failed to investigate.

Despite pervasive poverty, the emerging African American middle class began purchasing automobiles as soon as they could. This act was fundamentally a form of economic and psychological resistance, providing freedom from the mandatory discomfort, discrimination, and physical danger associated with segregated public transportation. While the private car offered a route around segregated trains (where Jim Crow cars were often dirtier, more dangerous, yet cost the same as regular tickets ), it also created new vulnerabilities, necessitating logistical support for fuel, repairs, and lodging far from home. This rise in professional and leisure travel among Black Americans, including salesmen, athletes, entertainers, and families, was the central catalyst for the guide’s necessity.

The historical reality of segregation extended well beyond the formal laws of the South. The unpredictable danger of decentralized racial hostility was perhaps best exemplified by the threat of “sundown towns”. These were thousands of communities, found across the country outside the traditional South, that enforced racial exclusion, often violently, forbidding non-white people from remaining within city limits after sunset. Being stranded or seeking service in one of these towns after dark posed an immediate, existential threat. The historical interpretation of this context demonstrates that the

Green Book was not a luxury guide; it was the essential infrastructure that protected the act of liberation enabled by the private car by mitigating the risk of pervasive, decentralized violence.

B. Victor Hugo Green: The Architect of Safety

The solution to these perils was devised by Victor Hugo Green, an African American postal worker and World War I veteran residing in Harlem, New York City. Green was motivated by his own difficult experiences traveling a segregated nation and modeled his guide on similar directories used by Jewish travelers who also faced widespread discrimination in many vacation spots. The first edition of the guide, published in 1936, began modestly, focusing solely on listings for Black-owned and non-discriminatory businesses within New York City.

The core mission of the publication was defined by safety and acceptance. As encapsulated by traveler Dino Thompson, the value of the guide was existential: it “didn’t tell you if a place had a good steak, or good seafood, or had a soft bed… it told you where you would be safe; it told you where you’d be welcome”. Green’s decision to launch the guide in a Northern city like New York demonstrates an early recognition that the requirement for safe haven was a pervasive national phenomenon, extending beyond explicit Jim Crow statutes to encompass tacit racial exclusion across the entire country. In response to growing demand, Green expanded the guide nationwide the following year , establishing a formal publishing office in Harlem by the 1940s and founding the Vacation Reservation Service travel agency in 1947 to further support Black travelers and businesses.

II. Chronology, Publication History, and Content Evolution

The publication history of the Green Book provides a clear temporal framework for the Black travel experience during the mid-20th century, detailing its expansion and eventual end upon the achievement of landmark civil rights legislation.

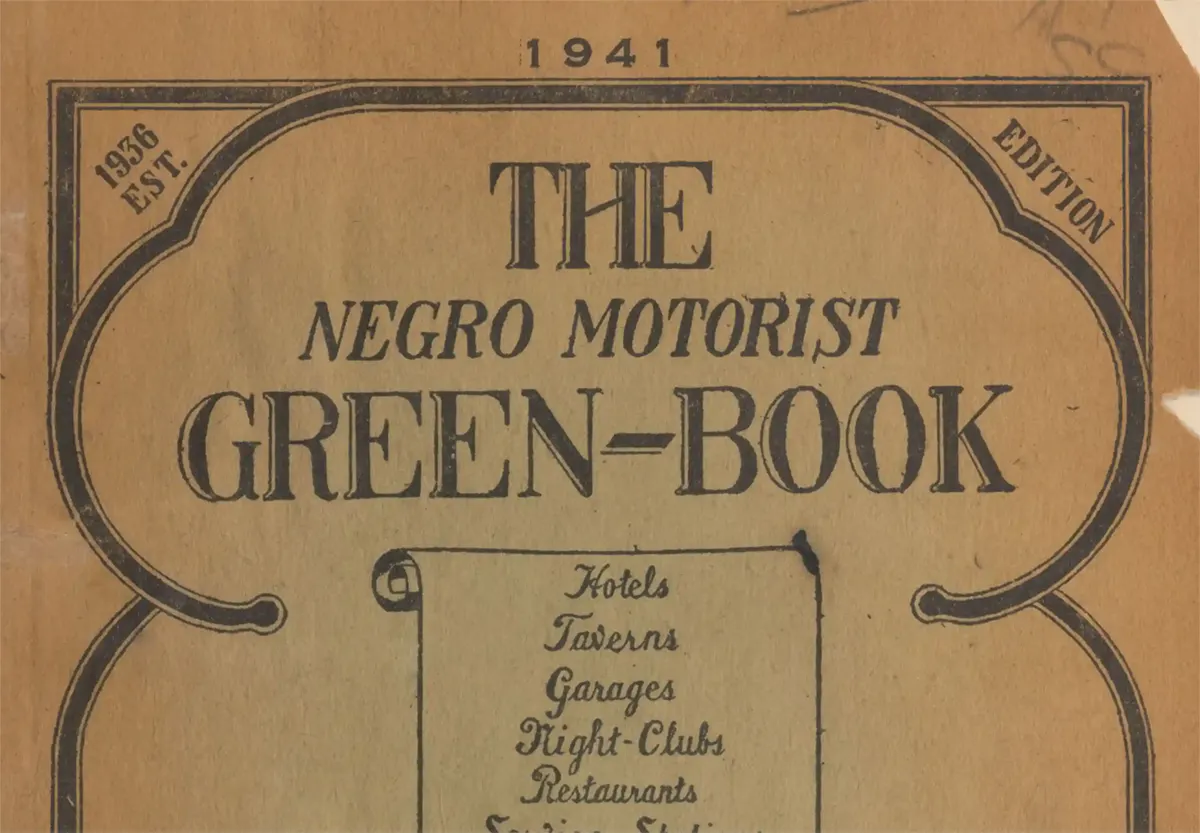

A. Publication Timeline and Names

The Negro Motorist Green Book was published annually from 1936 until the final edition in 1966–67. Throughout its 30-year existence, the guide underwent subtle title changes, including

The Negro Travelers’ Green Book and The Travelers’ Green Book, reflecting its expanding scope beyond solely motoring logistics.

Following its initial focus on New York City, the guide quickly expanded its scope to include listings nationwide. By 1949, the guide’s reach had extended internationally, incorporating verified safe havens in Bermuda and Mexico. This geographical expansion demonstrates the significant reach of the Black traveling community and the guide’s success as a comprehensive resource. The Green Book was a successful enterprise, achieving a substantial circulation of approximately 15,000 copies per year during its peak. This wide distribution was crucial in cementing its status as the indispensable “bible of black travel”.

B. The Types of Safe Havens Listed

The guide’s listings were purposefully comprehensive, ensuring that African American travelers could secure every necessary service required for a trip. Listings covered fundamental necessities such as hotels, motels, gas stations, and repair garages.

A defining feature of the listings was the prominence of private “tourist homes”. These were private residences where homeowners rented out rooms to travelers, filling critical gaps in areas where commercial accommodation was either non-existent or racially exclusionary. These homes represented a grassroots, community-centric model of hospitality, often managed by Black women, that functioned outside the formal, segregated economy. The extensive documentation of these private spaces highlights how the

Green Book mapped a robust “parallel world” of Black domestic entrepreneurship and hospitality. Beyond lodging, the guide listed establishments dedicated to leisure and personal care, including restaurants, bars, nightclubs, barbershops, and beauty salons.

C. Cessation: The Fulfillment of a Mission

The guide’s discontinuation was intrinsically linked to its founding philosophy. Victor Green had explicitly stated his desire for the guide to become obsolete, writing in 1949 that a future day would arrive “when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States”.

This aspiration was codified into law with the enactment of the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, which legally banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, gender, or country of origin. With Jim Crow and “separate but equal” legally dismantled, the publication of the guide was no longer necessary in principle. Though Green himself passed away in 1960, the books continued under the management of his wife, Alma, until 1962, and then by others until the final 1966–67 edition.

The decision to publish for three additional years following the Civil Rights Act reflects a crucial understanding of the social lag between legal decree and practical reality. The publishers recognized that de jure change would not instantly eliminate the risk of violence and discrimination (de facto segregation). Continuing publication provided a critical “buffer period” of verified safety while integration efforts slowly took hold across the country, prioritizing the continued physical security of travelers over immediate obsolescence.

The Green Book’s timeline, presented below, summarizes its key developmental phases:

Table 1: Key Chronology and Milestones of The Negro Motorist Green Book

Table 1: Key Chronology and Milestones of The Negro Motorist Green Book

Year/Range

Key Development / Edition

Contextual Significance

1936

First Edition (NYC Focus)

Initial proof of concept, focused locally where Green lived and worked, recognizing discrimination as a Northern issue.

1937–1966

National and International Expansion

Employed postal worker network for data collection across the U.S., Mexico, and Bermuda.

Early 1940s

Esso/Standard Oil Partnership Established

Secured the only major retail distributor, ensuring wide availability and guaranteed fuel access.

1960

Victor H. Green’s Death

Publication continued under his wife, Alma Green, demonstrating the guide’s institutional stability.

1964 (July)

Passage of the Civil Rights Act

Banned discrimination based on race, initiating the functional obsolescence of the guide.

1966–1967

Final Edition Published

Formal cessation of publication, fulfilling Green’s stated hope for racial equality after a transition period.

III. The Distribution Apparatus and Institutional Support

The widespread success and reliability of the Green Book were secured through a novel distribution network that bypassed conventional, segregated commercial channels by leveraging a federal employee network and a critical corporate partnership.

A. The Grassroots Network: Postal Workers as Information Brokers

Victor Green, who served as a full-time letter carrier for the U.S. Post Office until 1952, capitalized on his occupational status. He enlisted his national network of fellow African American postal employees to serve as the guide’s intelligence and verification brokers.

This grassroots network executed an “ambitious grass roots campaign” by soliciting advertising and gathering reliable, localized information from Black-owned businesses along their daily postal routes. This strategy effectively amounted to leveraging a neutral, federally-mandated infrastructure—the postal system—for a critical civil rights objective: compiling covert data on safe spaces. The use of trusted postal carriers provided an unparalleled, nationwide, and inexpensive system for updating listings annually, which was essential for maintaining the guide’s high credibility and reliability as a life-saving tool in a dangerous travel environment.

B. The Corporate Lifeline: The Esso Partnership

The guide’s logistical integrity was completed by a strategic corporate alliance with the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (Esso, now ExxonMobil). This partnership was facilitated by James A. Jackson, an African American marketing executive at Esso.

Esso became the only major retail distributor of the Green Book, circulating it through its extensive national network of Esso gas stations. This provision of guaranteed access to fuel and repair services was arguably as crucial as the lodging listings. For the Black motorist, being denied fuel or repair services could lead to being stranded in a hostile area, a potentially lethal prospect, particularly near sundown towns. By securing guaranteed service at Esso stations, Green ensured the fundamental operational integrity of Black automobile travel.

Esso’s role was underpinned by internal policies that were progressive for the era. The company actively supported Black individuals, with over a third of its dealers in the 1940s being Black franchisees. The company employed African Americans in various professional roles, including clerks and chemists. Esso’s involvement, including the use of its own maps and credit systems, turned the Green Book from a directory into a comprehensive system for achieving “safe miles” across the country, effectively circumventing the myriad local rules of segregation.

IV. The Economics of Survival and Cultural Impact

The Green Book’s significance lies in its profound ability to foster economic independence and validate the existence of a thriving, self-sufficient Black culture amidst oppression.

A. Fostering a Parallel Black Economy

The guide directed the spending power of the emerging Black leisure class toward businesses that would accept them, supporting a parallel economy critical for Black liberation. The book listed businesses owned by both Black entrepreneurs and verified non-discriminatory white owners. This channeling of capital fostered a community of “self-sufficient, talented, and successful Black businesses” necessary for sustained economic independence.

The economic utility of the Green Book was dual-faceted: it guaranteed survival necessities while simultaneously validating the right to leisure. It guided travelers to places where Black citizens could “eat, dance, talk, shop and relax,” showcasing a “Black experience not on the mainstream horizon, but it was there—real, alive, and thriving”. By mapping safe spaces for recreation (swimming, dancing, concerts), the guide normalized the Black community’s pursuit of the American Dream of personal mobility and leisure, serving as a political statement against imposed subjugation.

B. The Empowered Role of Black Women and Entrepreneurs

The Green Book was a significant force for the economic empowerment of Black women, who featured prominently as both travelers and entrepreneurs in the listings. Tourist homes and personal service businesses, such as beauty salons and funeral homes, were frequently woman-owned.

This phenomenon reflects a broader economic transformation: while the automobile industry elevated Black men into the middle class, the Black hair industry, championed by figures like Madam C. J. Walker, provided a similar pathway for Black women. The listed beauty shops and tourist homes functioned as crucial community hubs, providing local intelligence, service, and comfort to travelers. Furthermore, the guide’s editorial staff in later years was often composed almost entirely of women, demonstrating female leadership within the publishing venture itself.

C. Notable Users and Diplomatic Dimensions

The reliance on the Green Book was pervasive, necessary even for the most affluent and celebrated Black professionals. Famous entertainers, including Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and the pianist Dr. Don Shirley (whose life inspired later dramatization), depended on the guide for safe passage during segregated tours. The fact that successful figures still required such a directory underscores that discrimination was indifferent to wealth or fame.

The limitations imposed by segregation even affected international relations. The U.S. State Department’s Special Protocol Service Section, established to aid Black diplomats traveling within the country, considered issuing copies of the Green Book. The department ultimately declined, choosing instead to push for equal treatment for these diplomats, highlighting the extreme embarrassment segregation caused the United States on the global stage. Travelers themselves, like writer John A. Williams, confirmed that driving coast to coast required “nerve, courage, and a great deal of luck,” often supplemented by the guide.

V. Analysis of Security, Secrecy, and Protection Strategies

A central historical question concerns the measures taken to protect the listed businesses from organized racist violence, such as arson or targeted attacks. The evidence suggests that Victor Green’s security strategy was not based on explicit codes or passwords, but on a layered system of risk mitigation, obscurity, and community embedding.

A. The Strategy of Calculated Obscurity

There is no indication that the Green Book employed cryptic “codes” or deliberate linguistic obscurity to hide its listings. The book’s critical function as a survival tool mandated clarity and immediate understanding for its users.

The core security architecture was based on an intentional information asymmetry: the guide maintained high visibility to its target audience (African American travelers) while ensuring it remained “little known outside the African American community”. This external obscurity shielded the network from being easily co-opted or destroyed by organized white supremacist violence. If a verified, comprehensive list of Black safe havens had been easily accessible, it could have served as an ideal target list for mass attacks (similar to the collective violence used to enforce sundown towns ). The guide’s limited circulation thus prevented it from becoming an easy “hit list,” conferring safety through collective strategic silence.

B. Security through Decentralization and Location

Security for the listed businesses was intrinsically linked to their type and location. The inclusion of Tourist Homes provided critical security through physical decentralization. As private residences, these homes often maintained a low profile, blending into residential neighborhoods and avoiding the high visibility and exposure of commercial hotels on main routes, which were easier targets for arson or mob action.

Furthermore, these businesses, especially those embedded in tight-knit Black communities, benefited from an inherent layer of community protection. When a business was supported by local residents, the surrounding neighborhood functioned as an informal security apparatus, increasing the risk for external aggressors. The listing itself acted as a seal of trust, guaranteeing a stream of paying customers (the Black leisure class). This economic stability allowed businesses to remain viable and invested in their community, creating a virtuous cycle where economic success contributed to physical security.

Crucially, the ultimate security feature provided by the Green Book was risk mitigation. By verifying and mapping known safe routes, the guide allowed travelers to pre-emptively avoid vast areas of danger, particularly the thousands of all-white sundown towns.

C. Traveler Tactics: Layered Personal Security

The Green Book was one component of a broader, layered personal security strategy adopted by Black travelers. The car itself offered a defensive bubble, but travelers needed tactics for confrontations.

The most recognized tactic, especially when encountering police or hostile white residents, was the “chauffeur ruse”. A Black driver of an expensive car would wear or display a chauffeur’s cap and pretend he was employed by a white person. He would claim his family members were merely the “help” being driven home. This strategy required the performance of a subservient role to appease racist authorities, but it provided a non-threatening narrative that allowed the family to pass safely. Beyond these psychological defenses, many travelers relied on self-defense, as documented by John A. Williams, who traveled with a rifle and shotgun to protect himself against unexpected violence.

Table 2: Types of Green Book Safe Havens and Their Security Function

Category of Listing

Primary Function for Black Traveler

Strategic Security Significance (Implicit Protection)

Commercial Hotels/Motels

Structured lodging and dining.

Public visibility within the Black community, often located in urban centers with existing Black populations.

Tourist Homes

Private rooms rented by homeowners.

Decentralized and familial protection; low profile minimizes detection by hostile groups, filling crucial gaps outside main commercial areas.

Gas Stations (Esso)

Guaranteed fuel, mechanical service, and restrooms.

Solved the most lethal logistical risk: being stranded in hostile territory (sundown towns).

Barbers/Beauty Salons

Personal services and community gathering spots.

Supported Black women entrepreneurs; provided local intelligence and networking for travelers.

VII. Legacy and Preservation

The Green Book‘s powerful legacy continues through modern preservation efforts and its influence on current conversations about racial equity and information safety.

Despite the guide’s monumental historical significance, the physical record of its network is tenuous. It is estimated that less than 20 percent of the original sites listed in the Green Book remain standing today, with fewer still documented or preserved. This tremendous loss represents the decay of tangible history associated with Black economic empowerment and self-reliance that was largely ignored by mainstream preservation efforts after the period of integration.

Today, various organizations, including the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) and the National Park Service (NPS), are actively working to counteract this loss through grants and extensive historic surveys. The work of scholars like Candacy Taylor has been instrumental in reviving public interest and cataloging the remaining sites.

Furthermore, the core philosophy of the Green Book—providing a verified roadmap to safety—has been adapted for the digital age. Contemporary initiatives, such as the “Digital Green Book for the Culture,” aim to equip Black communities with the tools and information necessary to navigate digital spaces that are often hostile, protecting users from misinformation and online manipulation, confirming that the need for safe haven and reliable intelligence remains a crucial element of self-determination.

Origins & Creator

- Hidden Voices: Victor H. Green, Creator of the Green Book – NYC Schools

- Victor Hugo Green: Creator of the Green Book – America Comes Alive

- Victor H. Green – FHWA, U.S. Department of Transportation

- African-American Letter Carrier Who Created the Green Book – NALC

Historical Context

- The Green Book: A Historic Context – U.S. National Park Service

- The Legal History of Travel Discrimination – AAIHS

- The Negro Motorist Green Book – EBSCO Research Starter

- Sundown Towns – Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- Sundown Towns – Britannica

Exhibits & Preservation

- Virtual Exhibit: The Green Book – Smithsonian

- Traveling Exhibit: The Green Book – Smithsonian

- The Green Book: A Historic Travel Guide – National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Green Book Sites – National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Green Book Properties in the National Register of Historic Places – NPS

- Green Book Sites in Michigan – MiPlace

- Opening the Road: Victor Hugo Green and His Green Book – State Library of Ohio

Scholarship & Criticism

- The Problem with Oscar-Winning Movie “Green Book” – Bowdoin College

- Candacy Taylor Champions Black History in NYC with the Green Book – NYC Tourism

- What Do You Know About The Green Book? – The Momentary

Corporate & Community Involvement

- ExxonMobil Sponsors Smithsonian Green Book Exhibit

- ExxonMobil and The Green Book | Community Engagement

- Onyx Impact Launches Digital Green Book

Additional Resources

- The Green Book – National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

- Negro Motorist Green Book – National Museum of African American History & Culture

- The Negro Motorist Green Book (Reprint) – Sixth Floor Museum Store

- On the Road with the Green Book – American Heritage

- The Green Book: Documenting African American Entrepreneurs – Library of Congress

- Why Esso Backed Black Travelers in Jim Crow – YouTube

- The Negro Motorist Green Book – Wikipedia