Origins in Prison and a Bold Start (1930s–1940s)

Charlton Comics’ story begins in an unlikely place: prison. Italian immigrant John Santangelo Sr., who had been running a bootleg song-lyrics publishing business, was jailed in 1934 for copyright infringement. Behind bars he met Edward Levy, a disbarred attorney serving time for a local political scandal. The two became friends and, upon release, formed a publishing partnership with a simple handshake. Coincidentally, both men had infant sons named Charles, which inspired the name of their new venture: Charlton. By 1935 they were legally publishing licensed song-lyric magazines like Hit Parader. In 1940, they founded the T.W.O. Charles Company (for their two Charleses), which by 1945 evolved into Charlton Publications and launched Charlton’s comic-book line.

From the start, Charlton’s business model was unconventional yet cost-conscious. Santangelo and Levy set up shop in a large building in Derby, Connecticut, determined to do everything in-house – editorial, printing, and distribution – under one roof. This vertical integration was rare in publishing but saved them money by cutting out middlemen. They even created their own distributor and had an in-house printing press. Not just any press, either: Charlton acquired a gigantic second-hand press originally used to print cereal boxes. Because stopping and restarting this huge press was expensive and done only a couple times a year for maintenance, the company needed constant content to feed it. Comics proved the perfect filler. Charlton entered the comic book business in 1944–45 essentially to keep the presses rolling during downtime from their magazines. Their first comic title, Yellowjacket Comics, debuted in 1944

A Cheap, All-in-One Comics Factory

Charlton’s all-in-one production approach earned it a reputation as the ultimate low-budget comics factory. With their massive Derby plant running around the clock, the publishers were far more concerned with quantity than quality. “We had to keep the presses running around the clock… idle presses cost you a fortune,” explained one business manager. This relentless output meant Charlton flooded newsstands with comics in every genre – crime, horror, Westerns, war, romance, kid humor – whatever might sell just enough to justify its print run. Their integrated operation kept costs extraordinarily low.

However, there was a flip side: shoestring budgets and no-frills production values. Charlton paid some of the lowest page rates in the industry, meaning top-tier talent often went elsewhere. Those who did work for Charlton – often young or local artists on staff – had to crank out pages in a workmanlike, assembly-line fashion. Prolific scripter Joe Gill sometimes wrote 100 pages per week. The company prided itself on being unpretentious and efficient: no glossy paper, no big-name stars (at first), just cheap comics for the masses.

Charlton also developed peculiar habits to save money. They experimented with using a mechanical typesetting machine to letter speech balloons instead of paying a letterer. Many late-1950s Charlton books even cheekily credited the lettering to “A. Machine,” since it was done by a device rather than a person. The result was cramped, odd-looking text.

Charlton also became famous for odd issue numbering. To save on postal permits, they would continue numbering from canceled titles, which meant many series started with high, random numbers. Judomaster’s first solo issue, for instance, was #89.

Horror, Heroes, and a House StyleHorror, Heroes, and a House Style

Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, Charlton published a bit of everything: funny-animal comics, romance, crime, Westerns, war titles, and horror. They weren’t trend-setters so much as opportunists – whenever a genre got hot, Charlton jumped in. A house style emerged: straightforward, unflashy artwork by staff artists and simple, exposition-heavy scripts, usually by Joe Gill. This meat-and-potatoes approach earned Charlton comics a reputation for being very workmanlike – lacking pretension or polish, but also free of ego. The artists and writers were more blue-collar craftsmen than auteurs, grinding out stories for a steady paycheck.

The Silver Age “Action Heroes” (1960s)

Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, Charlton published a bit of everything: funny-animal comics, romance, crime, Westerns, war titles, and horror. They weren’t trend-setters so much as opportunists – whenever a genre got hot, Charlton jumped in. A house style emerged: straightforward, unflashy artwork by staff artists and simple, exposition-heavy scripts, usually by Joe Gill. This meat-and-potatoes approach earned Charlton comics a reputation for being very workmanlike – lacking pretension or polish, but also free of ego. The artists and writers were more blue-collar craftsmen than auteurs, grinding out stories for a steady paycheck.

Key figures included:

- Captain Atom, revived in 1965 with new Ditko art.

- Blue Beetle, reimagined by Ditko as Ted Kord, a tech-based hero with no powers.

- The Question, Ditko’s uncompromising vigilante with a blank face.

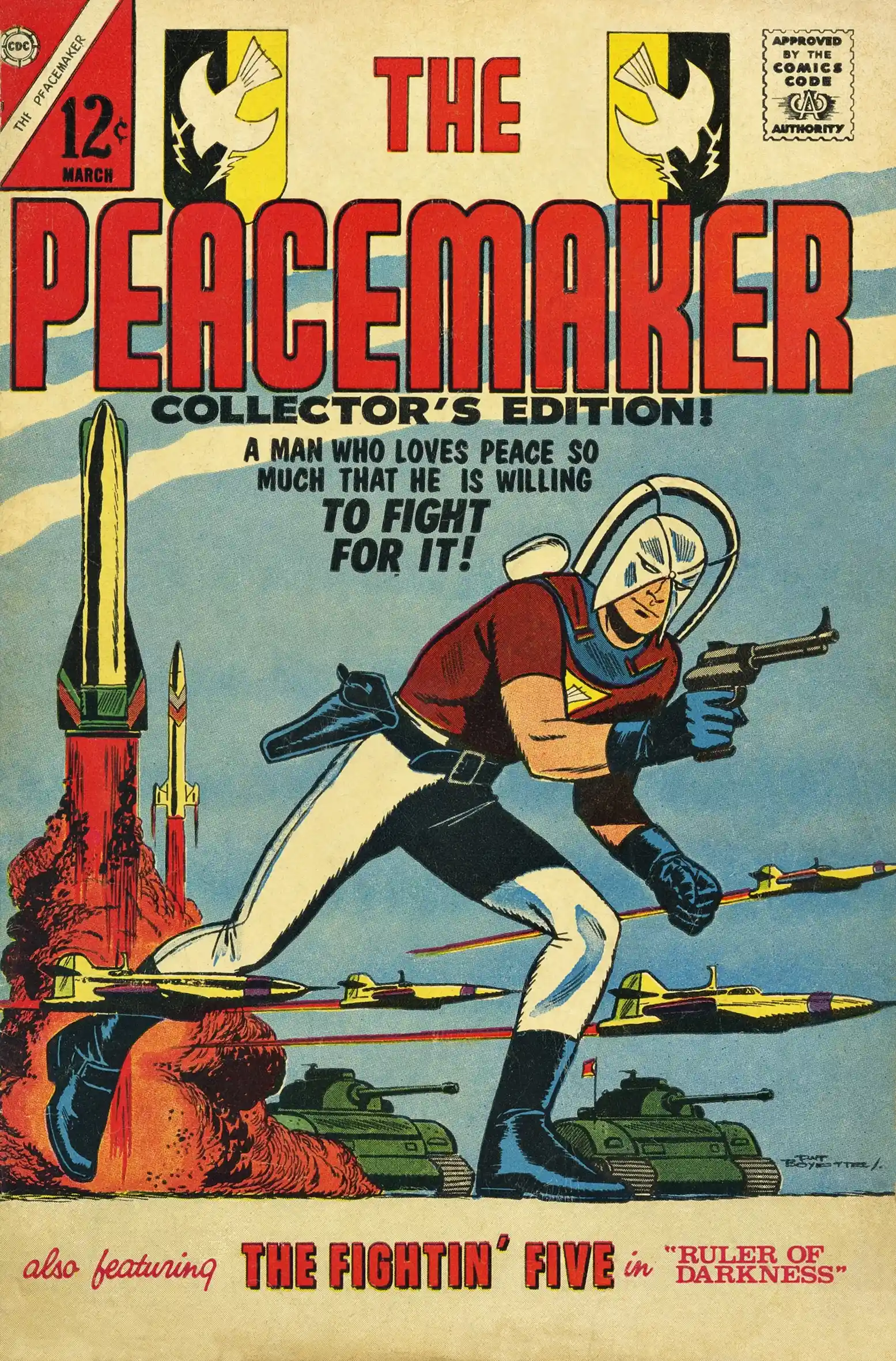

- Peacemaker, created by Joe Gill and Pat Boyette, a pacifist willing to fight for peace.

- Judomaster, a WWII hero trained in martial arts.

- Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt, created by Pete Morisi, a hero shaped by Eastern mysticism.

- Sarge Steel, a tough PI-turned-agent with a steel prosthetic hand.

Under Giordano, the Action Hero line attracted future stars like Jim Aparo and Denny O’Neil. Ditko’s contributions gave Charlton credibility, and many creators valued Charlton’s hands-off editorial approach. But by 1967–68, the books were canceled due to low sales, poor distribution, and Giordano’s departure to DC.

Last Hurrahs: The 1970s Revival and E-Man

The mid-1970s brought a creative renaissance. Writer Nicola “Nick” Cuti and artist Joe Staton introduced E-Man in 1973, a humorous, whimsical superhero series about a sentient energy being. It became a cult favorite. At the same time, young fans from the fanzine world – the “CPL Gang,” including John Byrne, Roger Stern, and Bob Layton – got professional starts at Charlton. They contributed to series like Doomsday +1 and Midnight Tales and even produced Charlton’s in-house fanzine. This wave of enthusiasm couldn’t overcome Charlton’s financial decline, and many of these creators were soon hired away by Marvel and DC.

Decline and Fall (1980s)

By the 1980s, Charlton’s old presses were obsolete. Rising paper costs, declining distribution, and inability to modernize doomed the line. Reprint programs and small revivals failed. The comic division suspended publication in 1984, briefly revived in 1985, and finally closed for good that same year. Charlton Publications as a whole lingered on a few more years with magazines before closing in 1991. The Derby plant was demolished in 1999.

From Charlton to DC—and the Watchmen Echo

Even as Charlton faded, its characters found new life. DC Comics acquired the rights to Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, the Question, Peacemaker, Nightshade, Judomaster, Thunderbolt, and others. Initially, DC asked Alan Moore to use these characters in a new series. When DC balked at his darker plans, he created original analogues instead. The result was Watchmen. Rorschach echoes the Question; Dr. Manhattan magnifies Captain Atom; Nite Owl draws from Blue Beetle; the Comedian channels Peacemaker; Ozymandias reflects Thunderbolt; and Silk Spectre has roots in Nightshade.

Charlton’s heroes also joined the DC Universe directly, beginning with Crisis on Infinite Earths in 1985. Today, Charlton-born heroes like Blue Beetle, Captain Atom, the Question, and Peacemaker are still active in DC stories, with Peacemaker even starring in a hit TV show decades later.

Legacy of the Little Company That Could

Charlton Comics ultimately closed after forty years, undone by its own frugal methods and outdated machinery. Yet its influence was far greater than its sales might suggest. It gave early breaks to major creators like Steve Ditko, Denny O’Neil, and John Byrne. It produced cult favorites like E-Man. And its Action Heroes became the backbone for Watchmen and new additions to the DC Universe. For a company born in a jail cell and fueled by a cereal-box press, Charlton left a lasting, unlikely mark on comics history.

Primary Historical Sources

The Charlton Empire – Comic Book Artist #9 (TwoMorrows Publishing)Charlton Comics – Wikipedia

Watchmen Connection

Watchmen Comic Has Roots in Connecticut – The Central Recorder

Technical & Production History

The Rise of Digital Lettering, Part 2 – Todd Klein’s BlogThe Origin of That Familiar “Font” Used in Comic Book Lettering – Boing Boing BBS

Character & Series Information

Judomaster by Charlton – Key Collector ComicsE-Man – Wikipedia

Additional Referenced Sources

Note: The document also references the following sources that don’t have direct URLs provided:

- Cooke, Jon B., & Irving, Christopher. Comic Book Artist #9 – “The Charlton Empire: A Brief History of the Derby, Connecticut Publisher” (TwoMorrows, 2000)

- Connecticut History / chs.org – Charlton’s Derby operations and printing press

- DC Database – Charlton series data