Overview

On March 16, 1968, during the Vietnam War, soldiers of the U.S. Army’s Charlie Company entered the hamlet of My Lai (Son My village) and carried out a brutal massacre of unarmed Vietnamese civilians. The atrocity, which claimed the lives of over 300 villagers including women, children, and elderly, remained hidden from the public for over a year. This report delves into the roles and reputations of key officers involved—Lieutenant William Calley and Captain Ernest Medina—and how leadership failures contributed to the tragedy. It also highlights the courageous actions of Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr. and his crew members, Glenn Andreotta and Lawrence Colburn, who intervened to stop the killing. A detailed timeline of events leading up to the massacre and the fallout afterwards is included to provide chronological context.

Background and Leadership of Charlie Company

War Context and Unit Frustration: The My Lai operation took place in the immediate aftermath of the Tet Offensive, at a time when U.S. troops were suffering mounting casualties in Quảng Ngãi province – a Viet Cong stronghold rife with mines and booby traps. In the weeks leading up to My Lai, Charlie Company (1st Battalion, 20th Infantry of the 23rd “Americal” Division) had endured sniper and mine attacks that killed or injured several of its men, fueling anger and a desire for revenge among the troops. Morale was low and frustration was high, as the company had taken losses without ever engaging a clearly identifiable enemy. This was the volatile environment in which the unit’s leaders prepared for the mission at My Lai.

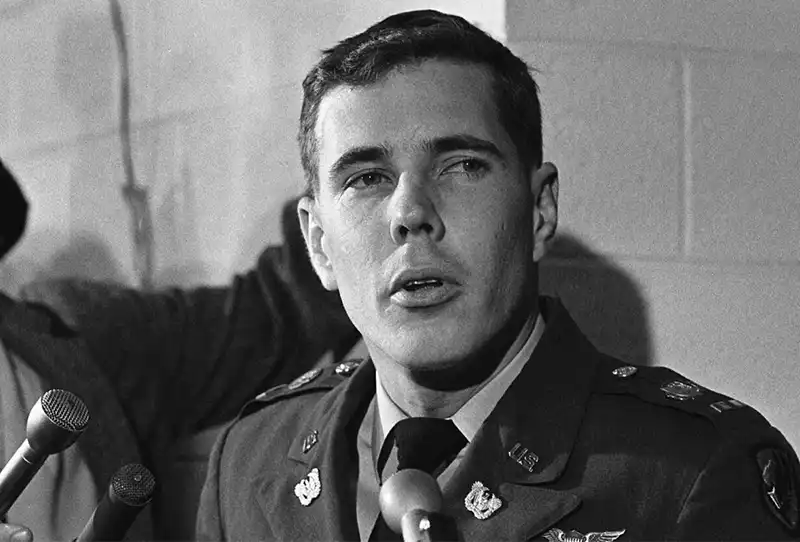

Lt. William Calley – Inexperienced and Unrespected: Charlie Company’s 1st Platoon was led by 2nd Lt. William Calley, a 24-year-old junior officer. Calley had been rushed through Officer Candidate School and had limited command experience. By most accounts, he was young, inexperienced, and incompetent as a leader.

His own men held him in low regard; many soldiers in his platoon resented Calley, and even his commanding officer, Captain Ernest Medina, often treated Calley with open hostility and disrespect in front of the troops. This lack of respect from both subordinates and superiors left Calley with a poor leadership reputation. Some historians suggest that Calley may have felt pressure to prove himself “tough” to gain the esteem of his unit, given that he did not naturally command it. The stage was set for a possible overreaction in combat, as Calley’s eagerness to assert authority could combine with the company’s vengeful mindset.

Capt. Ernest Medina – Charismatic but Aggressive: Captain Ernest L. Medina was the commanding officer of Charlie Company. In contrast to Calley, Medina was a career officer who had a strong influence over his men. He had led the company since training in Hawaii, where he earned the nickname “Mad Dog” for the tough, fiery demeanor with which he drove his men.

Medina was respected by many in the company for his combat experience and hard-driving style, though that respect often stemmed from fear of his explosive temper. On the eve of the My Lai mission, Medina briefed his troops in a highly charged meeting. He urged his men to be especially aggressive on the upcoming operation and assured them that no civilians would be present in the hamlet during the assault. The soldiers were told that My Lai was a Viet Cong bastion and that any Vietnamese present would likely be enemy or enemy sympathizers. This briefing, coming right after an emotional memorial service for a fallen comrade the day before, further primed the men of Charlie Company for violence and revenge. Notably, the pre-mission pep talk did not include any reminder of the rules of engagement regarding non-combatants – effectively giving the troops tacit license to treat everyone in My Lai as hostile. Medina’s leadership style and instructions contributed to a permissive atmosphere in which normal restraints were stripped away.

The Massacre of March 16, 1968

Operation Begins – “Kill Anything That Moves”: At 7:30 AM on March 16, 1968, the men of Charlie Company, including Calley’s 1st Platoon, were airlifted by helicopter into the vicinity of My Lai (coded as “My Lai 4” on U.S. maps). They expected to engage the Viet Cong’s 48th Battalion, believed to be hiding in the area, and were told that virtually all civilians would be away at market. The troops landed “poised for engagement with their elusive enemy,” but in reality they encountered almost no resistance – in fact, not a single shot was fired at the Americans upon landing. Despite the lack of enemy fire, the soldiers had been psyched up by their superiors with comments like, “This is what you’ve been waiting for — search and destroy — and you’ve got it,” and they entered My Lai firing indiscriminately.

Mass Killings and Atrocities: What unfolded over the next four hours was an indiscriminate slaughter of unarmed villagers. Lt. Calley in particular aggressively directed his platoon to round up and execute civilians. According to eyewitness accounts, Calley ordered his men to shoot people as they ran from their homes and to systematically clear the village by fire. Several old men were bayoneted; women and children were shot at close range as they tried to surrender or flee. In one infamous incident, Calley herded a group of Vietnamese villagers (dozens of women, children, and infants) into an irrigation ditch. He then ordered his soldiers to mow them down with automatic rifle fire, personally shooting many of the victims as well. By late morning, virtually every living being the troops encountered – men, women, children, and even livestock – had been killed. There were reports of horrific abuse: at least one girl was raped and then murdered by members of the company, and numerous homes were torched. Estimates of the dead vary, but the U.S. Army’s own later inquiry confirmed that more than 300 unarmed civilians were killed in My Lai during the operation. (Vietnamese sources put the number at 504.) The company, for its part, suffered only a single casualty (a self-inflicted wound) during the massacre.

Leadership (In)action – Calley and Medina’s Roles: Both Calley and Medina were present on the ground during the massacre. Calley, as a platoon leader, was observed personally shooting elderly people and children, and ordering his men to keep killing “anything that moves.” Soldiers later testified that Calley was acting in an overzealous manner, as if to demonstrate his authority. Some of Calley’s men were initially unsure about killing civilians, but many went along with his orders, perhaps due to command pressure and the revenge-fueled atmosphere. Captain Medina’s exact actions during the massacre remain a matter of some dispute. Medina was moving around the area as the killings were underway, and several soldiers reported seeing Medina shoot at least two unarmed Vietnamese individuals himself (including one wounded woman who Medina allegedly executed at close range). Medina later denied giving any explicit order to kill women and children; at his trial, he claimed that he never intended for civilians to be harmed and that he even turned away one woman he encountered before hearing gunfire and discovering she had been shot. However, other evidence suggested Medina had indeed set an overall tone that day that condoned brutality – for example, radio chatter indicated Medina knew civilians were being killed yet did not immediately intervene. In fact, higher-level commanders flying overhead had to prod Medina for information before he finally radioed a cease-fire order to Charlie Company, telling them to “knock off the killing,” which effectively ended the massacre around 11:00 AM. By that time, the carnage was largely complete. The failure of leadership was stark: senior officers like Medina (and Colonel Frank Barker, the task force commander overhead) had some idea atrocities were occurring, but took little action to stop it until much of My Lai lay in smoldering ruin.

Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr. and Crew: Heroic Intervention

While most of Charlie Company participated in or tacitly enabled the massacre, one helicopter crew heroically attempted to halt the slaughter. Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr. was a 24-year-old Army helicopter pilot flying scout support that morning for the mission. Along with his two crewmen—Specialist Four Glenn Andreotta (crew chief) and Specialist Four Lawrence Colburn (door gunner)

Thompson was conducting reconnaissance overhead in an OH-23 Raven helicopter. Their assignment was to draw enemy fire (if any) and mark wounded on the ground for medical evacuation. Within the first 20 minutes, Thompson realized something was terribly wrong. He had marked the locations of several wounded Vietnamese civilians with smoke grenades and radioed for medics. After a brief refueling, he returned to find that those wounded people he had tried to help had been shot dead by the American ground troops. Thompson and his crew then witnessed an even more shocking scene: they saw Captain Medina walk up to a wounded Vietnamese woman lying on the ground, prod her with his foot, and shoot her dead. Circling further, Thompson saw a ditch “full of bodies” and observed soldiers firing into it. He radioed to his superiors in anger that “there’s an awful lot of unnecessary killing going on down there.” Realizing that a massacre was in progress, Thompson decided to intervene directly against his own forces.

Spotting a group of frightened villagers (mostly women and children) huddled near a bunker, pursued by U.S. soldiers, Thompson landed his helicopter between the American troops and the fleeing civilians. Turning to his crew, Thompson gave an extraordinary order: he told Andreotta and Colburn to point their mounted machine guns at the U.S. soldiers and to open fire on them if they tried to harm the civilians. Essentially, Thompson was prepared to engage in an armed standoff with fellow Americans to protect Vietnamese non-combatants. Colburn and Andreotta, though just enlisted men, did not hesitate to back Thompson; they trained their M60 machine guns on the approaching infantry, implicitly warning them to hold fire. Thompson then got out and confronted the leader of the pursuing U.S. squad (Lt. Stephen Brooks), telling him he wanted to help evacuate the civilians in the bunker. When one of the soldiers suggested tossing a grenade into the shelter, Thompson angrily insisted they hold their fire until he could get the people out safely. Defying the chain of command, Thompson and his crew proceeded to escort a group of about 11 villagers (half a dozen children, women, and elderly) out of the bunker and to a safe area. Thompson even convinced two other helicopter gunships nearby to land and airlift these civilians to safety at a rear base, away from the mayhem.

After saving that group, Thompson’s team wasn’t done. As they took off again, Andreotta spotted movement in the corpse-filled ditch they’d seen earlier. Thompson landed a third time near the ditch, and Andreotta waded into the mass of bodies. In an act of immense bravery and compassion, Andreotta managed to pull out a survivor – a young boy who was still alive beneath the pile of the dead and dying. The child was placed aboard the helicopter with Thompson and Colburn, and flown to safety at a hospital in Quảng Ngãi. Thompson’s quick thinking and the crew’s courage likely saved at least a dozen or more innocent lives that day, marking one bright spot in an otherwise horrific event.

By approximately 11:00–11:30 AM, Thompson returned to the U.S. base at nearby Chu Lai and immediately reported the massacre to his superiors, demanding that the slaughter be stopped. His field report up the chain prompted Lt. Col. Frank Barker (the operation commander overhead) to radio Capt. Medina and order an immediate cease-fire, finally halting the killing at My Lai. In essence, it took the moral courage of a low-ranking warrant officer to bring the murders to an end when leadership on the ground had failed.

Ostracism and Later Recognition: Thompson’s actions, while heroic, were not rewarded by the Army at the time. To the contrary, he was ostracized by many of his fellow soldiers and commanders for intervening and later speaking out. In the weeks after My Lai, Thompson’s superiors submitted him and his crew for the Bronze Star medal, but the citation falsely described their heroism as rescuing civilians from crossfire (omitting that Americans were the ones shooting). Thompson was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, but the commendation was a whitewash that praised him for diverting enemy fire; disgusted, Thompson threw the medal away because it misrepresented the truth. Meanwhile, Thompson’s crew were quietly transferred to other units. In fact, following his outspoken criticism of My Lai, Thompson was assigned to increasingly dangerous missions – his helicopter was shot down multiple times in the following weeks, and in one crash in April 1968 he was severely injured (breaking his back) and nearly killed. Tragically, crewman Glenn Andreotta was killed in action on April 8, 1968, just three weeks after My Lai, before he could see any justice done.

For many years, the role of Thompson and his men was not widely recognized; during the subsequent investigations and trials, Thompson was even vilified by some as a traitor to the Army, accused of undermining his fellow soldiers by blowing the whistle on the massacre. It was only decades later that the U.S. military and public fully acknowledged the crew’s heroism. Exactly 30 years after the massacre, in March 1998, Hugh Thompson Jr. and Lawrence Colburn were awarded the Soldier’s Medal (the Army’s highest award for bravery not involving enemy conflict), and the same honor was posthumously given to Glenn Andreotta. At the belated award ceremony, officials praised these men for having “the ability to do the right thing even at the risk of their personal safety,” calling them examples of true moral courage. Thompson, who had quietly returned to civilian life after the war, lived to see this recognition (he passed away in 2006), while Colburn continued to speak about My Lai as the last surviving member of the crew until his death in 2016. Their intervention at My Lai stands as a remarkable example of integrity amid unspeakable atrocity.

Cover-Up and Whistleblowing

Initial Cover-Up by the Army: In the immediate aftermath of the My Lai massacre, the U.S. Army’s chain of command actively covered up the events. A false after-action report was filed by Charlie Company and higher officers, claiming a major victory against Viet Cong forces. It reported 128 enemy fighters killed and only 3 weapons captured, implicitly labeling virtually all the dead civilians as Viet Cong combatants. This glaring discrepancy (so many “enemy” dead with so few weapons recovered) did not initially raise alarms up the chain. Brigade commander Colonel Oran Henderson conducted a cursory inquiry into the civilian deaths, but he accepted a convenient cover story: he reported that around 20 non-combatants might have been inadvertently killed by crossfire or stray fire, and he deemed the incident an unfortunate accident. Major General Samuel Koster, the Americal Division commander, actually halted a deeper investigation by higher headquarters and allowed the brigade to self-investigate, which violated standard protocol. No formal report of wrongdoing ever reached the public or the Pentagon at that time. Warrant Officer Thompson’s immediate complaints on March 16 about the massacre were largely ignored or buried – his superiors did not pursue his reports or debrief him in depth, as doing so would have exposed the enormity of the crime. Instead, the Army quietly transferred key personnel (for example, Calley was rotated to a desk job, and Thompson to another unit) and hoped the incident would fade away.

For more than a year, My Lai remained an official secret. Soldiers in Charlie Company were ordered not to speak of what happened, and some who had refused to participate or who objected (such as PFC Michael Bernhardt) were intimidated into silence. Captain Medina, according to later testimony, explicitly warned his men right after the massacre not to discuss it, threatening them with prosecution if they did. One soldier later recounted that in the weeks following My Lai, those in the company who knew the truth were treated with “blatant carelessness” – for instance, men like Bernhardt who might talk were given especially dangerous assignments as a form of punishment. The wall of silence held for months, even as some low-level rumors about civilian killings in Vietnam began circulating within the Army.

Ronald Ridenhour’s Letter – Breaking the Silence: The eventual exposure of the massacre owed much to the determination of a single ex-GI named Ronald Ridenhour. Ridenhour was not present at My Lai, but he served in the same area and had friends in Charlie Company. In April 1968, not long after the massacre, he began hearing disturbing firsthand accounts from returning soldiers about an entire village wiped out by Americans. Over the next several months, Ridenhour quietly gathered information: he spoke to multiple members of Charlie Company, confirming the gruesome details and even learning the names of some key perpetrators like Lt. Calley. After being discharged from the Army, Ridenhour decided to bring the matter to light. On March 18, 1969, he wrote an 8-page letter detailing everything he had learned about My Lai, including specific allegations of mass murder, and sent copies of this letter to dozens of high-ranking government and military officials (including members of Congress, the Pentagon, and the White House). In his letter, Ridenhour implored the authorities to investigate the “dark and bloody” event that had been covered up. This remarkable whistleblowing letter was hard for the Army to ignore. Congressman Mo Udall forwarded Ridenhour’s letter to the Army Chief of Staff, and by mid-1969 the Army had opened a serious inquiry.

Investigations Sparked: The Army’s Inspector General undertook a preliminary investigation in mid-1969, led by Colonel William Wilson and later by General William Peers. As a result of these probes, the truth of My Lai gradually emerged. In late August 1969, investigators interviewed members of Charlie Company in depth. Lt. William Calley was identified by many as a central figure in the killings, and by September 1969 Calley was formally charged with multiple counts of murder. Notably, this was still an internal Army legal action and not public knowledge yet.

Public Exposure – Seymour Hersh’s Scoop: The American public remained unaware of My Lai until journalists got wind of the story. In November 1969, freelance investigative reporter Seymour Hersh learned of Calley’s secret indictment and interviewed Ridenhour and some soldiers. Hersh then published a bombshell news article on November 12, 1969, revealing that U.S. troops had massacred civilians in Vietnam and that one Lt. “William L. Calley Jr.” was being court-martialed for murder. Hersh’s story, picked up by major newspapers, caused an immediate outcry. A few days later, the Cleveland Plain Dealer printed explicit photographs taken by Army photographer Ron Haeberle showing piles of dead villagers at My Lai, which shocked the world. The massacre could no longer be denied or concealed; My Lai became front-page news and intensified the already raging debate about the Vietnam War.

Public Reaction: News of the massacre and cover-up sent shockwaves through America. The revelations in late 1969 came at a time when the war was already deeply divisive and unpopular. The mainstream press expressed horror and outrage at the gruesome details. Many Americans were sickened and questioned how such an atrocity could have been committed by their own troops. The My Lai story further eroded support for the war, fueling the anti-war movement’s argument that Vietnam had corrupted U.S. moral integrity. However, reaction was not uniform: some steadfast supporters of the war refused to believe the reports or downplayed My Lai by arguing that Communist forces committed worse atrocities. Others defended Calley and the soldiers, claiming they were under the stress of war or that My Lai was a tragic exception. Indeed, a segment of the public (particularly some veterans and conservatives) viewed Lieutenant Calley as a scapegoat and later rallied to his defense when he was tried. Nonetheless, the My Lai massacre greatly tarnished the U.S. Army’s reputation and raised pressing questions about leadership, discipline, and accountability in Vietnam.

Military Investigations and Trials

The Peers Commission Findings: In the wake of the public outcry, the Army expanded its investigation. A board of inquiry headed by Lt. Gen. William R. Peers was convened in late 1969 to uncover exactly what happened at My Lai and why it had been covered up. Over the next months, Peers’ team interviewed hundreds of witnesses. The Peers Commission’s report (completed in March 1970) was scathing: it documented not only the mass murder of civilians at My Lai, but also a systemic failure of leadership and a concerted cover-up. Peers recommended charges against numerous individuals. As a result, 14 Army officers were eventually accused of crimes in connection with My Lai, either for the killings or the subsequent cover-up. These included officers up the chain of command who had suppressed reports or failed to investigate (for example, Colonel Henderson and Major General Koster were implicated for covering up information). The Army’s Judge Advocate General corps proceeded to draw up charges where they believed they had evidence to prosecute.

Charges and Courts-Martial: The primary focus was on Lieutenant William Calley, who became the first person to stand trial. Calley was charged with premeditated murder in the deaths of 22 Vietnamese civilians (a number chosen as representative of those he was directly implicated in killing). His court-martial began on November 17, 1970, and lasted until March 1971. It was the first public trial related to the massacre and received enormous media attention, often described as putting the Vietnam War itself on trial.

During the proceedings, Calley’s defense was that he was following orders from Captain Medina to kill anyone in the village – a claim Medina vehemently denied. After hearing months of testimony (including accounts from soldiers who had witnessed Calley’s actions and villagers who survived), a panel of six military officers found Calley guilty of murder on March 29, 1971. He was convicted of murdering 22 civilians and sentenced to life in prison at hard labor.

Calley’s conviction was the lone success in prosecuting My Lai perpetrators – and even that outcome proved fleeting. Following the verdict, a significant portion of the American public rallied to Calley’s side, viewing him as a scapegoat who had been made to take the blame for a broader military failure. Many felt that higher-ups who set the conditions for My Lai (or even ordered it) were evading responsibility while a low-ranking lieutenant was sacrificed. A nationwide “Free Calley” movement emerged: thousands of telegrams and letters poured in to the White House, a hit song “The Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley” hit the airwaves, and even some state legislators symbolically demanded clemency. Under tremendous public pressure, President Richard Nixon took the unprecedented step of intervening in a military justice case. On April 1, 1971 – just a day after Calley was sent to Fort Leavenworth prison – Nixon ordered him removed from the stockade and placed under house arrest pending appeal. Over the next months and years, Calley’s sentence was steadily reduced by the military appeals process. In August 1971, the Secretary of the Army commuted his life term to 20 years. Later, in 1974, a federal judge overturned Calley’s conviction on procedural grounds (ruling that pretrial publicity had prejudiced the trial), and although that decision was later appealed, Calley was effectively free. In the end, Calley served only about 3½ years under house arrest and a mere few months actually confined in a military prison. He was released on parole in November 1974, to the dismay of those who had hoped to see full justice for My Lai.

While Calley’s trial was underway and dominating headlines, the Army also pursued charges against Captain Ernest Medina and others. Captain Medina was charged in 1970 with complicity in the massacre (including the murder of a small number of specific civilians and assault by causing grievous harm). Medina’s court-martial took place in 1971, after Calley’s. In Medina’s trial, a crucial question was whether he had explicitly ordered the killing of non-combatants or knew about the atrocities as they happened. Medina testified in his own defense, denying that he had ever given an illegal order. Notably, a key eyewitness against him—PFC Michael Bernhardt, who had seen Medina’s actions—withdrew from testifying, reportedly under pressure. Lacking clear evidence that Medina had explicitly sanctioned the massacre, the jury of five combat officers acquitted Medina of all charges on September 22, 1971. Medina left the Army shortly thereafter; although he was not convicted, the stigma of My Lai followed him. (The Army quietly refused to promote him, and Medina lived out his life in the private sector, never speaking much about the incident. He admitted after the trial that he “had not been completely candid” during the investigations – essentially acknowledging he withheld some truth to avoid disgracing the military.)

Besides Calley and Medina, few others were held accountable. In total, at least 13 other men were charged with direct involvement in the killings, but most of those cases never went to full trial or resulted in acquittals due to insufficient evidence or witnesses unwilling to testify. Several soldiers of lower rank (such as platoon sergeants and riflemen who participated) had charges dropped or were found not guilty. On the matter of the cover-up, the Army charged a dozen officers, but again accountability was scarce. Brigadier General Oran Henderson (who had been a colonel commanding the 11th Brigade) was court-martialed for covering up the massacre, but he too was acquitted in 1971. Major General Samuel Koster, the division commander, was not court-martialed; however, he was demoted and officially censured by the Army for failing to report truthfully on My Lai, effectively ending his career. In the end, the only person convicted of murder at My Lai was Lt. Calley, and he served a very light sentence in relative comfort, a result that many viewed as a miscarriage of justice.

Throughout these proceedings, the role of the helicopter crew and other whistleblowers also came to light. Hugh Thompson testified before both the Peers Commission and at the trials, recounting what he witnessed and the threats he made to stop the killings. Thompson’s testimony, along with that of others like Lawrence Colburn and Ron Ridenhour, helped establish the facts of the massacre. However, Thompson in particular faced hostile questioning and public scorn from some who believed airing the Army’s dirty laundry was treasonous. It was only years later that the institutional view shifted to praise Thompson and his men as exemplars of Army values (as noted, they eventually received the Soldier’s Medal for their courage).

Aftermath and Legacy

The My Lai massacre left an indelible stain on the U.S. Army’s record and had a lasting impact on how the Vietnam War was perceived. When the story broke in late 1969, it further polarized American society. To many, My Lai epitomized the moral quagmire of Vietnam: it raised the question of how ordinary soldiers could commit such heinous acts and whether the blame lay with the individuals or the war itself. The incident became a rallying point for anti-war activists, who cited it as evidence that the war was unjust and dehumanizing for American troops. Even some supporters of the war were forced to confront uncomfortable truths about the conduct of U.S. forces. The Pentagon, embarrassed by My Lai, instituted new training on the laws of war and emphasized ethical conduct in counterinsurgency operations. In the decades since, My Lai has been used as a cautionary case study in military ethics courses, illustrating the importance of lawful orders and moral courage to refuse illegal orders.

For the Vietnamese, My Lai was one tragedy among many in a long war, but it became symbolic of civilian suffering. In Sơn Mỹ village, a memorial and museum now commemorate the 504 innocent lives lost. The site includes a somber stone monument and displays that describe the massacre. Some American veterans have returned in peacetime to participate in reconciliation efforts; for example, a peace park and a hospital were established in Quảng Ngãi with the help of American and Vietnamese volunteers. Yet for survivors and the families of victims, the horror could never be undone.

William Calley lived a relatively quiet life after his release. He remained one of the most controversial figures from the war. Decades later, on August 20, 2009, Calley publicly apologized for his role at My Lai, saying, “There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse.” This brief apology, given at a Kiwanis Club meeting in Georgia, was met with mixed responses – some felt it was too little, too late, while others appreciated the acknowledgement. Calley passed away in 2024, taking many of the mysteries of My Lai to his grave.

Captain Ernest Medina lived until 2018, never publicly expounding on the massacre beyond his statements at trial. In later years, he expressed regret that he had not been more forthcoming about what happened, though he maintained he never ordered the murder of civilians. Medina’s name, like Calley’s, remains associated with My Lai in history books as an example of command failure.

Perhaps the most positive legacy of My Lai lies in the actions of those who resisted it. In 1998, exactly 30 years after the massacre, survivors from My Lai stood alongside American veterans Hugh Thompson and Lawrence Colburn in a ceremony that honored the helicopter crew’s heroism. The U.S. Army’s Chief of Staff at the time formally acknowledged that Thompson and his men saved lives and upheld the highest ideals of the U.S. military on that dark day. Their story is now taught to soldiers as an example of moral courage: the notion that there is a duty to disobey unlawful orders and to protect innocent life, even on the battlefield. Likewise, Ron Ridenhour is remembered for his integrity in doggedly pursuing the truth — an award for investigative journalism, the Ridenhour Prize, was established in his memory after his death in 1998.

My Lai’s fallout also influenced military policies. The Pentagon tightened its reporting requirements for civilian casualties and created training to prevent “enemy dehumanization.” However, critics note that atrocities in war did not stop with My Lai; incidents from later conflicts (such as the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq or the Haditha killings) suggest the lessons of My Lai must be continually relearned. As of today, the name “My Lai” remains a sobering shorthand for American war crimes. It challenges us to remember the capacity for both brutality and compassion in war: brutality in the blind obedience that led soldiers to slaughter innocents, and compassion in the brave intervention of Thompson’s crew and the principled whistleblowing of Ridenhour. My Lai stands as a grim reminder of the importance of accountability and ethics in military operations, and the event’s legacy endures as a call to “never forget” the victims and the moral responsibilities of armed forces.

Timeline of Key Events (1968–2009)

Early 1968: Charlie Company operates in Quảng Ngãi province, Vietnam, taking casualties from mines and snipers. On February 12, 1968, the unit suffers its first fatality (a popular sergeant shot by a sniper), contributing to growing anger and frustration among the troops. In the following weeks, more men are wounded by booby traps, although the company has yet to engage any identifiable Viet Cong forces.

March 15, 1968 (Day Before the Massacre): Charlie Company holds an emotional memorial service for a recently fallen comrade, which heightens the soldiers’ desire for revenge. Later that day, Captain Ernest Medina briefs the company about the next morning’s assault on Son My village (My Lai). He emphasizes that the area is a Viet Cong stronghold and tells his men to attack aggressively, assuring them that no civilians will be present (the villagers supposedly would be at market). This pre-mission pep talk reminds the troops of their losses and does not instruct them to safeguard non-combatants, effectively setting a permissive tone.

March 16, 1968 – The My Lai Massacre: At around 7:30 AM, Charlie Company is inserted by helicopter near My Lai. They arrive expecting to engage enemy combatants, but encounter only villagers. Despite receiving no incoming fire, Lt. William Calley and other platoon leaders order their men to open fire on anyone they see. Over the next four hours, U.S. soldiers massacre hundreds of unarmed civilians – more than 300 villagers are killed, including women, children, and babies. Calley personally directs the killings in one area, rounding up dozens of people and executing them with machine-gun fire in an irrigation ditch. Several incidents of rape and brutal abuse occur amid the slaughter. Captain Medina is present in the village and, according to some accounts, shoots at least a few civilians himself (though he later denies this).

March 16, 1968 – Thompson’s Intervention: Around 9:00–10:00 AM, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr., piloting a scout helicopter, witnesses the ongoing massacre from the air. Horrified by U.S. troops firing on unarmed people, Thompson lands his helicopter to intervene. He confronts Lt. Calley and other soldiers, and when he sees American ground troops pursuing more villagers, Thompson places his helicopter between the troops and the civilians. He orders his door gunner Lawrence Colburn and crew chief Glenn Andreotta to point their guns at the American soldiers, warning that he will shoot if the troops continue attacking the civilians. Thompson and his crew then help evacuate a group of about 10–15 Vietnamese civilians (mostly women and children) to safety with the help of other helicopters. Before leaving the area, Andreotta rescues a wounded child from a pile of bodies in a ditch, demonstrating extraordinary bravery. Thompson’s actions likely prevent further killings. At approximately 11:00 AM, after Thompson reports the situation up the chain of command, a cease-fire order is finally radioed to the ground units, halting the massacre.

March 16–17, 1968 (Aftermath on the Ground): As Charlie Company exits My Lai, they report mission success. Initial field reports falsely claim that 128 Viet Cong fighters were killed in a fierce battle, with minimal civilian casualties. In reality, virtually all the dead are unarmed villagers and only 3 weapons were recovered, a fact omitted in early reports. Warrant Officer Thompson files an official complaint about the massacre with his commanding officers on the same day, but his report is stifled and not acted upon. That evening, division commander MG Samuel Koster congratulates some of the troops, having received no truthful accounting of the civilian deaths.

Late March 1968: An Army inquiry at the brigade level, led by Col. Oran Henderson, reviews the My Lai operation. This internal investigation is perfunctory. Col. Henderson’s report (submitted within weeks of the incident) acknowledges around 20 civilian deaths but claims they were accidental, caused by stray crossfire or grenades, and asserts that the vast majority of those killed were enemies. No further action is taken by the Americal Division command, and MG Koster ensures the investigation goes no higher, effectively burying the incident.

April 1968: The three members of Thompson’s air crew are each nominated for the Bronze Star medal (a commendation typically awarded for heroic achievement in combat). The Army awards these medals with fabricated citations that credit the men for helping Vietnamese civilians caught in crossfire, without admitting that American troops were the ones inflicting harm. Thompson is also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, but the citation he’s given falsely portrays him as rescuing a young girl from enemy fire (making no mention that he stopped an American massacre). Thompson, angered by the deceit, later throws the medal away. Meanwhile, rank-and-file rumors about the massacre start to spread among soldiers in Vietnam, but no official acknowledgment is made.

Mid-1968 – Early 1969: Most of Charlie Company’s men finish their Vietnam tours and rotate back to the U.S. or to other units. The My Lai incident remains officially hidden. Some soldiers who were at My Lai (like PFC Michael Bernhardt) try to raise concerns to superiors or in letters home, but their accounts are either disregarded or not publicized. Ronald Ridenhour, a former door gunner from a different unit, hears about the massacre from friends and begins his own investigation in 1968. By late 1968, Ridenhour has gathered enough eyewitness accounts to be convinced that a mass atrocity occurred.

March 18, 1969: Ron Ridenhour mails a detailed letter to 30 prominent U.S. officials (including members of Congress, the Pentagon, and the President), describing the My Lai massacre in vivid detail and urging a full investigation. This letter is the catalyst that forces the Army to take action. Individuals such as Congressman Morris Udall and others forward the letter to Army leadership, demanding answers.

April–August 1969: The U.S. Army launches a secret investigation under its Inspector General. Colonel William Wilson is sent to Vietnam to interview members of Charlie Company and uncover what happened. By the summer of 1969, enough evidence has been gathered to identify key participants. Calley, who is still on active duty (stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia), is interrogated and placed under suspicion.

September 5, 1969: The Army formally charges Lt. William Calley with multiple counts of premeditated murder for the deaths of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. He is the first person charged in connection with the massacre. At this point, the case is still within military channels and not known to the public.

November 12, 1969: The My Lai story becomes public. Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh publishes the first press report about the massacre, after tracking down Lt. Calley’s lawyer and learning of the secret charges. Hersh’s article reveals that U.S. troops killed hundreds of civilians in a Vietnamese village and that Calley is facing court-martial. The story is picked up by media worldwide, sparking immediate outrage and disbelief.

November 20, 1969: The Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper publishes graphic photographs taken during the massacre by Army photographer Ronald Haeberle, including images of piles of dead women and children. The photos provide undeniable proof of the atrocity and galvanize public attention. Around the same time, additional eyewitness accounts from soldiers and Vietnamese survivors begin to appear in the press. The U.S. public and international community react with shock, horror, and condemnation.

Late 1969: In response to public revelations, the Army expands its inquiry. Lieutenant General William Peers is appointed to lead an official board of inquiry into the My Lai incident and the subsequent cover-up. Over the next several months (December 1969 – March 1970), the Peers Commission gathers testimony from hundreds of individuals, from privates up to generals, to piece together the full story and identify all responsible parties.

March 6, 1970: The Peers Commission concludes its investigation. Its report implicates dozens of officers and soldiers in wrongdoing, either for participating in the massacre or for suppressing information. Following the Peers report, the Army levels charges against 14 officers, including Captain Medina and several high-ranking officers, for offenses ranging from murder to dereliction of duty in covering up the crime.

March 17, 1970: The Army announces charges against Capt. Ernest Medina for the murder of Vietnamese civilians and assault with intent to kill a civilian at My Lai. Medina vehemently denies the charges, and his case is referred to a general court-martial.

Late 1970: Other individuals charged in connection with My Lai include Colonel Oran Henderson (for covering up the massacre) and Major General Samuel Koster (for failure to report truthfully and obstruction). These cases progress through pre-trial hearings. Some charges against lower-level participants are dropped due to lack of evidence or uncooperative witnesses.

November 17, 1970: Lt. William Calley’s court-martial begins at Fort Benning, Georgia. The trial is closely followed by the media. Calley is charged with 6 specifications of premeditated murder (encompassing the deaths of 22 identified civilians). He is the only person from Charlie Company to be tried for direct involvement in the killings at this time.

December 1970: Specialist Four Lawrence Colburn (Thompson’s door gunner) testifies before the Peers Commission (and later at trials) about what he witnessed from the helicopter on March 16, 1968. His testimony, along with Thompson’s, provides crucial, independent confirmation of the massacre and the attempts to stop it. Other soldiers, like PFC Michael Bernhardt and SP4 Chester “Butch” Gruver, also give testimony either to Peers or at Calley’s trial, describing Calley’s actions and the mass killings.

March 29, 1971: The verdict in Calley’s trial is delivered. Calley is found guilty of the premeditated murder of 22 Vietnamese civilians and is sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labor. He is the only member of the U.S. military convicted in relation to My Lai’s killings. The conviction marks a rare instance of an American officer being held accountable for war crimes against Vietnamese civilians.

April 1, 1971: Responding to a fierce backlash from a segment of the American public and politicians who argue Calley was scapegoated, President Richard Nixon intervenes. Nixon directs the Army to remove Calley from prison and place him under house arrest at Fort Benning while his case is on appeal. This extraordinary action comes after nationwide protests calling for Calley’s release: for example, the “Free Calley” movement had seen rallies, petitions, and even some state officials lowering flags in support of Calley.

June 1971: The court-martial of Col. Oran Henderson for covering up the massacre concludes. Henderson is acquitted of charges that he willfully suppressed information about My Lai. (During the trial, Henderson maintained he had investigated and found no deliberate massacre, a claim the jury apparently accepted.) With Henderson’s acquittal, no senior officers are convicted of any cover-up related offenses.

August 20, 1971: The convening authority at Fort Benning reviews Calley’s sentence and reduces it from life to 20 years imprisonment. Calley remains under comfortable house arrest, not in a standard prison cell, during this period.

September 22, 1971: Captain Medina’s court-martial ends in acquittal. The jury finds Medina not guilty on all counts, concluding that the evidence is insufficient to prove he ordered or directly participated in the intentional killing of civilians. The outcome is swayed in part by Medina’s own testimony and the lack of eyewitnesses willing to implicate him in specific crimes. After his acquittal, Medina resigns from the Army. He eventually moves into civilian work, living a quiet life and avoiding the spotlight.

1972–1974: As appeals in Calley’s case continue, military review boards further cut down his sentence. In August 1972, the Secretary of the Army commutes Calley’s sentence to 10 years (from the earlier 20). Calley remains under nominal confinement at Fort Benning. In late 1973, a federal district judge orders Calley’s release pending habeas corpus review of the case, citing concerns over whether Calley received a fair trial. Finally, on November 9, 1974, after legal back-and-forth, William Calley is released on parole, having effectively served only about 3½ years under custody (mostly in house arrest) for the murders at My Lai. He receives a dishonorable discharge from the Army but no further imprisonment.

1976: The Vietnam War ends (with the fall of Saigon in April 1975 and final U.S. withdrawal). In the war’s aftermath, My Lai fades somewhat from headlines, but it remains a subject of military study and public soul-searching. The U.S. Army incorporates My Lai into training curricula to stress lawful conduct in war and preventing atrocities.

March 6, 1998: In a ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., the U.S. Army formally honors Hugh Thompson Jr., Lawrence Colburn, and (posthumously) Glenn Andreotta. The three men are awarded the Soldier’s Medal for heroism, 30 years after their lifesaving actions at My Lai. Thompson and Colburn receive their medals in person; Andreotta’s family accepts his posthumous award. The Army’s recognition, though long overdue, is a significant moment of acknowledgment for the courage it took to stop the massacre. Days later, on March 10, 1998, the U.S. Senate also enters a commendation into the record, praising Thompson, Colburn, and Andreotta as true heroes and role models of moral conduct in war.

August 19, 2009: In a public speech at a Kiwanis Club in Columbus, Georgia, former Lt. William Calley breaks his long silence and offers a brief apology for his role in the My Lai massacre. Calley says, “There is no one more sorry than I am” and that he feels remorse every day for what happened. This apology comes 41 years after the events. It is one of the very few public statements Calley ever made about My Lai. (He would pass away in 2024.)

2011: The My Lai Peace Park is inaugurated in Sơn Mỹ, Vietnam, near the site of the massacre, as a joint Vietnamese-American project to promote peace and healing. Survivors and some U.S. veterans attend the ceremony, emphasizing reconciliation and the hope that such a tragedy never recurs.

Present Day: My Lai is remembered as one of the darkest chapters of U.S. military history. The name “My Lai” has become synonymous with the potential for moral breakdown in war, and it serves as a stark reminder of the importance of leadership, training, and individual conscience in preventing atrocities. The story of Hugh Thompson Jr. and his crew is now taught to American service members as an example of moral courage, reinforcing the ideal that upholding humanity and law is a soldier’s duty even amid the chaos of combat.

Primary Sources Listed

Source 1: The My Lai Massacre | American Experience | PBS

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/vietnam-my-lai-massacre/

Referenced in citations: 1, 2, 3, 12, 13, 62, 80, 90, 91

Source 2: The Vietnam War and the My Lai Massacre | Gilder Lehrman Institute

https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/essays/vietnam-war-and-my-lai-massacre

Referenced in citations: 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 15, 20, 45, 46, 47, 48, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 64, 67, 72, 73, 74, 76, 77, 79, 84, 85, 86, 87

Source 3: Meet the Participants | American Experience | PBS

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/my-lai-selected-men-involved-my-lai/

Referenced in citations: 6, 7, 8, 14, 17, 21, 22, 23, 29, 30, 33, 37, 40, 43, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 60, 61, 63, 65, 66, 68, 69, 70, 71, 75, 78, 81, 88, 89

Source 4: Lawrence Colburn – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_Colburn

Referenced in citations: 16, 18, 19, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 32, 36, 38, 44, 82, 83

Source 5: Glenn Andreotta – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glenn_Andreotta

Referenced in citations: 34, 35, 39, 41, 42

Citation Distribution Summary

Total citations in document: 91 numbered references

Total unique sources: 5 sources

Note on Sources

The document appears to have drawn from these five main sources, with the PBS American Experience series and the Gilder Lehrman Institute article being the most heavily cited. The Wikipedia articles on Lawrence Colburn and Glenn Andreotta provided specific details about the helicopter crew’s heroic intervention.