I. Introduction: Framing the Discourse and Defining Terms

The enduring historical narrative that conflates the experiences of Irish indentured servants and transportees with African chattel slavery represents a significant challenge to the accurate understanding of labor history in the colonial Atlantic World. This challenge is not merely one of academic semantics; rather, it involves the persistence of a fringe pseudohistorical narrative—the “Irish slaves myth”—that is actively utilized for contemporary political ends. This report establishes the necessity of a rigorous historical intervention by definitively separating the distinct legal systems of indentured servitude and race-based chattel slavery, verifying the demographic context of European migration, and tracing the specific origins and modern digital propagation of this false equivalence.

Contextualizing the Query: The Necessity of Historical Precision

The premise that Irish migrants were primarily involved in indentured servitude or penal transportation, rather than perpetual chattel slavery, is historically accurate and upheld by academic research. The history of unfree labor in the British colonies is complex, involving harsh conditions and forced migration for multiple groups. However, historical accuracy mandates that the legal and hereditary nature of African chattel slavery be differentiated from the finite, contractual bondage experienced by Europeans. The notion of Irish “slavery” functions as a mechanism to distort these complex colonial labor dynamics. Therefore, the methodological framework employed here involves a synthesis of colonial legal history, established demographic data, and critical analysis of the disinformation networks responsible for promoting this revisionism.

Defining Chattel Slavery vs. Indentured Servitude: A Primer in Colonial Law

The distinction between indentured servitude (IS) and chattel slavery (CS) is fundamentally legal, institutional, and, by the late 17th century, racial. To understand why the “Irish slaves” myth is a fallacy, the defining characteristics of each system must be rigorously established.

Indentured Servitude (IS)

Indentured servitude was a system of contracted labor where typically poor whites, including English and Irish individuals, signed an agreement—or had one signed on their behalf—granting room, board, and often apprenticeship in exchange for labor over a fixed duration.

- Duration and Inheritance: Indentured servitude was never lifelong, nor was the unfree status hereditary. Servants typically worked for a term of four to seven years in exchange for passage across the Atlantic. Crucially, the children of indentured servants were born free.

- Legal Status: Indentured servants were legally defined as English subjects and, however harsh their treatment, possessed legally defined rights. They were entitled to receive “freedom dues” upon completing their contract, which could include land (often 25 acres), supplies, or clothes. They even retained the capacity to sue their masters for mistreatment or contract violations, a protection unavailable to enslaved Africans. Laws were in place to protect some of their rights, even if punishments for infractions were harsh.

Chattel Slavery (CS)

Chattel slavery, imposed upon Africans and their descendants, was an altogether different institution, codified by colonial assemblies to maximize permanent economic utility through total dehumanization.

- Legal Status as Property: The foundation of chattel slavery was the legal definition of the enslaved person as movable property, or “chattel”. This status stripped the individual of any legal personality or rights guaranteed by English common law.

- Duration and Inheritance: This system was perpetual and hereditary. Enslavement was lifelong, and the status was passed through the mother (known as partus sequitur ventrem). This hereditary clause was essential for ensuring a permanent, self-reproducing, race-based workforce for colonial planters.

- Race-Based Codification: As documented in Ibram Kendi’s detailed chronicle, racist ideas were utilized by colonists in the 1620s and 1630s to codify African people as the sole group subject to perpetual enslavement.

The distinctions are summarized clearly in the comparative table below, demonstrating that the experience of bonded labor, while sometimes brutally similar, rested upon fundamentally opposing legal foundations.

Table 1: Comparative Legal Status of Unfree Labor in the Colonial Atlantic

Characteristic

Indentured Servitude (European)

Chattel Slavery (African)

Duration of

Service

Finite, contractually limited (typically 4–7 years)

Perpetual (Lifelong)

Legal

Status

Possessed limited legal rights, considered subjects; masters had defined responsibilities (e.g., freedom dues)

Source

Defined as chattel (property), stripped of legal personality

Source

Inheritance of Status

II. The Dichotomy of Unfree Labor in the Colonial Atlantic

The Harsh Reality of Indentured Servitude and Penal Transportation

Indentured servitude played a vital role in the early development of British North America and the Caribbean, constituting between one-half and two-thirds of the immigrants who arrived in the American colonies. This system was conceived by entities like the Virginia Company as a necessary means to supply cheap labor to care for vast tracts of land, given the high cost of transatlantic passage.

The life of an indentured servant was undoubtedly severe. Servants were bound to their masters and could be bought, sold, and physically punished. Labor and disease conditions, especially in the early Caribbean, were brutal, leading many to die before completing their contracts. Punishments for running away or, in the case of women, becoming pregnant, included extension of the contract, sometimes indefinitely. Furthermore, not all European servants arrived willingly; significant numbers, particularly the Irish, were forcibly transported as convicts, vagrants, or political prisoners—a practice heightened during the Cromwellian conquest (1649–1653), where thousands were “Barbadosed” against their will.

Despite the evident dehumanization and cruelty, the status of these indentured servants, even the involuntary transportees, was fundamentally different from chattel slavery. They entered into a temporary bondage (sometimes coerced) with the expectation of achieving freedom, legally defined as their birthright as subjects. The existence of laws designed to protect their rights and regulate their terms of labor, and the legal mechanism allowing them to sue for mistreatment, confirms they were not defined as property. The 1659 pamphlet

Englands Slavery, or Barbados Merchandize, which exposed the harsh treatment of indentured servants, caused a scandal precisely because it related to the expendability of the lower classes, not the legally sanctioned, perpetual property status of Africans.

This focus on the lived experience of brutality to establish equivalence with slavery fundamentally obscures the institutional, racial, and economic permanence that defined chattel slavery. While both groups suffered, the essential distinction lies in the law’s treatment of the person: one retained conditional humanity and subjecthood, the other was reduced to goods.

The Institutionalization of Race-Based Chattel Slavery

The transition from reliance on European indentured servants to African chattel slavery was a deliberate, gradual, and comprehensive legal evolution driven by economic necessity. The supply of English indentured servants began to decline sharply after the 1660s, forcing planters to seek a more stable, permanent labor source.

The legal codification of race-based slavery began in earnest in the mid-17th century. The seminal piece of legislation, the Barbados Slave Code of 1661, officially titled An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes, solidified the distinction. The preamble of this code established that Black slaves would be treated as “men’s other goods and Chattels”.

This pivotal legislation explicitly denied enslaved people the most basic rights guaranteed to English subjects. For instance, the code stated that, because of their “brutish” nature, slaves did “not, for the baseness of their condition, to be tried by the legal trial of twelve men of their peers”. Furthermore, if a slave were to “suffer in life or member” while under punishment by his master—an event that the law notes “seldom happens,” minimizing the brutality—the master would not be “liable to any fine therefore”. This granted enslavers de facto immunity for mutilation or death inflicted during punishment.

The Barbados Slave Code of 1661 became highly influential, serving as the basis for subsequent slave codes adopted across the British American colonies, including Jamaica, Carolina (1696), and influencing laws in Virginia and Maryland. This legal framework explicitly and systematically codified racial difference, ensuring that status was both perpetual and hereditary through the mother.

The decline of white indentured servitude did not end with the rise of slavery; rather, the inherent instability and costs associated with time-limited European labor models contributed directly to the accelerated adoption of racial slavery as an economic solution. The colonial elite required a self-reproducing workforce that could be controlled completely and permanently, a requirement met only by constructing a legal status based on racial dehumanization. The economic utility of a permanent, disposable workforce, made legally possible by racial codification, is the essential element the “Irish slaves” myth ignores when it seeks to define “slavery” merely by the physical conditions of labor.

III. Irish Migration and The Demographics of Early Colonial Labor

To fully address the user query, which correctly notes that English indentured servants were more numerous than Irish ones, an examination of the demographic reality of early colonial labor is necessary.

Quantifying European Indentured Servitude

Indentured servitude was a constitutive factor in the early development of colonial America, attracting approximately 320,000 servants from across Britain and Western Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. These immigrants, primarily poor individuals aged 18 to 25, accounted for about 80 percent of white immigrants during that era.

The demographic data confirms the user’s premise: the majority of these servants originated from England. The historical flow of English servants was substantial, though it dried up beginning in the 1660s and fell off dramatically around 1680, forcing planters to seek alternatives.

In contrast, estimates for Irish migration specifically place the total number of Irish people who traveled to the West Indies during the entire 17th century at around 50,000. Historian Thomas Bartlett suggests this figure is comprised of roughly 40,000 voluntary indentured servants and 10,000 individuals sent involuntarily through penal transportation. While 50,000 represents a significant forced migration event, the total population of English indentured servants vastly exceeded this figure, confirming that the English, not the Irish, were the predominant group migrating to the colonies under contract.

Table 2: Estimated European Indentured Migration to the British Colonies (17th–18th Centuries)

Origin Group

Estimated Total Indentured/Contracted Servants

Notes/Context

Total White European Indentured Servants

Approximately 320,000

Source

Representing 50% to two-thirds of all immigrants to the American colonies

Source

Penal Transportation and the Legal Status of the “Barbadosed” Irish

The peak period for the involuntary transport of Irish persons occurred during the Cromwellian Protectorate (1649–1653). Individuals classified as political prisoners, vagrants, or the “undesirable” were forcibly sent overseas, a practice often termed “Barbadosing”. This constituted a significant episode of forced labor and immense hardship.

However, even those transported unwillingly were legally distinct from slaves. They were not sold “in perpetuity” as property, but were serving fixed terms or sentences. Their status was one of temporary transportees or convict servants, maintaining a legal claim to freedom that was permanently denied to the enslaved African population.

The decline of the unstable and eventually expensive system of European indentured labor directly necessitated the adoption of African chattel slavery. When the majority labor source (English servants) diminished, the colonial elite sought a mechanism—racial codification—to create a self-reproducing, permanent, and disposable workforce. This demographic and economic causality demonstrates that the system of racial slavery was engineered precisely because European labor, including the Irish, possessed a finite legal contract that led to freedom and eventual competition with the elite.

The Obfuscation of Irish Complicity

A critical function of the “Irish slaves myth” is the strategic obfuscation of documented Irish involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and plantation economy. By framing the entire Irish experience as one of perpetual victimhood—even equating it to the level of African chattel slavery—the narrative diverts attention from the historical reality that many Irish individuals transitioned successfully into the colonial structure.

Irish merchants and planters participated actively in the slave economy. Some Catholic Irish migrants, particularly in the Caribbean, managed to acquire land and subsequently acquired “first in land, and then in enslaved Africans,” thereby joining the planter elite. Furthermore, in the Antebellum U.S. South, Irish immigrants were known to serve as overseers for African slaves and acquired a reputation, even among abolitionists like James Redpath, of being “the most merciless of negro task-masters”. The myth thus functions not only to minimize African suffering but also to shield certain segments of Irish history and the Irish diaspora from confronting their historical participation in the economic structures of racial slavery.

IV. Origins of the Pseudohistorical Narrative: The ‘Irish Slaves’ Myth Genesis

The narrative of “Irish slaves” is a contemporary phenomenon, largely confined to fringe discourse until the late 20th century, before its dissemination dramatically accelerated online. Its modern iteration can be traced to specific non-academic and sensationalist popular works published in the 2000s that deliberately blurred the legal distinctions between servitude and chattel slavery.

The Intellectual Seed: Conflation in Popular History and Fiction

The current, virulent form of the myth finds its foundation in three influential print sources, which professional historians have identified as the basis for the “meme of the Irish slave”.

- Sean O’Callaghan’s To Hell or Barbados (2000): This book, written for the general public, is perhaps the most critical text for establishing the modern myth. O’Callaghan explicitly asserted that Cromwellian prisoners “were not sent as indentured servants, but were sold in perpetuity… They became the first white slaves in relatively modern times, slaves in the true sense of the word, owned body and soul by their masters”. This claim of “slaves in the true sense of the word” is a direct, yet erroneous, attack on the legal historical distinction, positioning the experience of the Irish transportees as identical to chattel slavery.

- Don Jordan and Michael Walsh’s White Cargo (2008): Though published by an academic press (NYU Press), this work has been criticized for adopting a sensationalist approach. It claimed to provide “proof that the brutalities usually associated with black slavery were, for centuries, also inflicted on whites”. Critics argue that the book helped popularize the “reductive fallacy that ‘slavery was slavery’ in the history of British America,” enabling white nationalist groups to seize upon it as “evidence”.

- Kate McCafferty’s Testimony of an Irish Slave Girl (2002): This historical novel, which chronicles the fictionalized experience of an Irish girl kidnapped and shipped to the Caribbean, also contributed to the narrative blurring. The book suggested that indentured servitude was “usually indistinguishable from slavery because the terms of the indenture could be prolonged indefinitely”. While intended to highlight the immense suffering of indentured women, the fictional use of the term “slave girl” conflated the legal realities for mass audiences.

The fact that popular works often received positive reviews and gained traction in academic-adjacent spaces, such as academic bookshops and through endorsement by figures like J.M. Coetzee, lent a veneer of historical legitimacy to the concept of “white slavery”. This failure by popular historical gatekeepers to rigorously maintain the crucial legal and institutional distinctions provided the necessary citations for the subsequent digital disinformation campaigns.

Table 3: Key Foundational Texts of the “Irish Slaves” Myth

2000 – To Hell or Barbados

Sean O’Callaghan

Popular History; explicitly argued that Irish transportees were “slaves in the true sense of the word”

2002 – Testimony of an Irish Slave Girl

Kate McCafferty

Fictionalized Historical Novel; claimed indentured servitude was “usually indistinguishable from slavery”

2008 – White Cargo

Don Jordan & Michael Walsh

Popular History; criticized for popularizing the “reductive fallacy” that “slavery was slavery”

The Narrative’s Core False Claims

The myth, as disseminated online, simplifies complex history into several easily digested, inflammatory falsehoods:

- The “Cover-Up”: A conspiracy theory alleging that historians and the media are intentionally suppressing evidence of Irish slavery.

- Comparative Suffering: The false claim that Irish slaves were treated worse than African slaves, often citing exaggerated numbers or historical fabrications.

- Forced Breeding: The specific, highly racialized, and historically unsubstantiated claim that Irish women were forcibly bred with African men to create a subservient, mixed-race workforce. This particular claim explicitly leverages anti-miscegenation anxiety prevalent within white nationalist circles.

These claims rely heavily on subjective feelings of oppression or anecdotal brutality to override the objective framework of colonial law. While the harshness of indentured servitude is undeniable, the legal definition of chattel status—permanent, inherited, and property-based—is the decisive factor, not the relative suffering of individuals under different systems of unfreedom.

V. Digital Weaponization and Modern Social Media Propagation

The advent of online platforms provided the perfect medium for the “Irish slaves myth” to transition from fringe print history into a pervasive, resilient piece of digital disinformation.

The Meme Economy: Transition to Digital Disinformation

The myth has been in widespread circulation since at least the 1990s and has been continually disseminated through online debates and comment sections on major news and celebrity sites. Research tracking the meme’s prevalence indicates a colossal reach: one estimate suggests the narrative was shared at least 4 million times between 2014 and 2016, with peak popularity often coinciding with public discussions of racial justice.

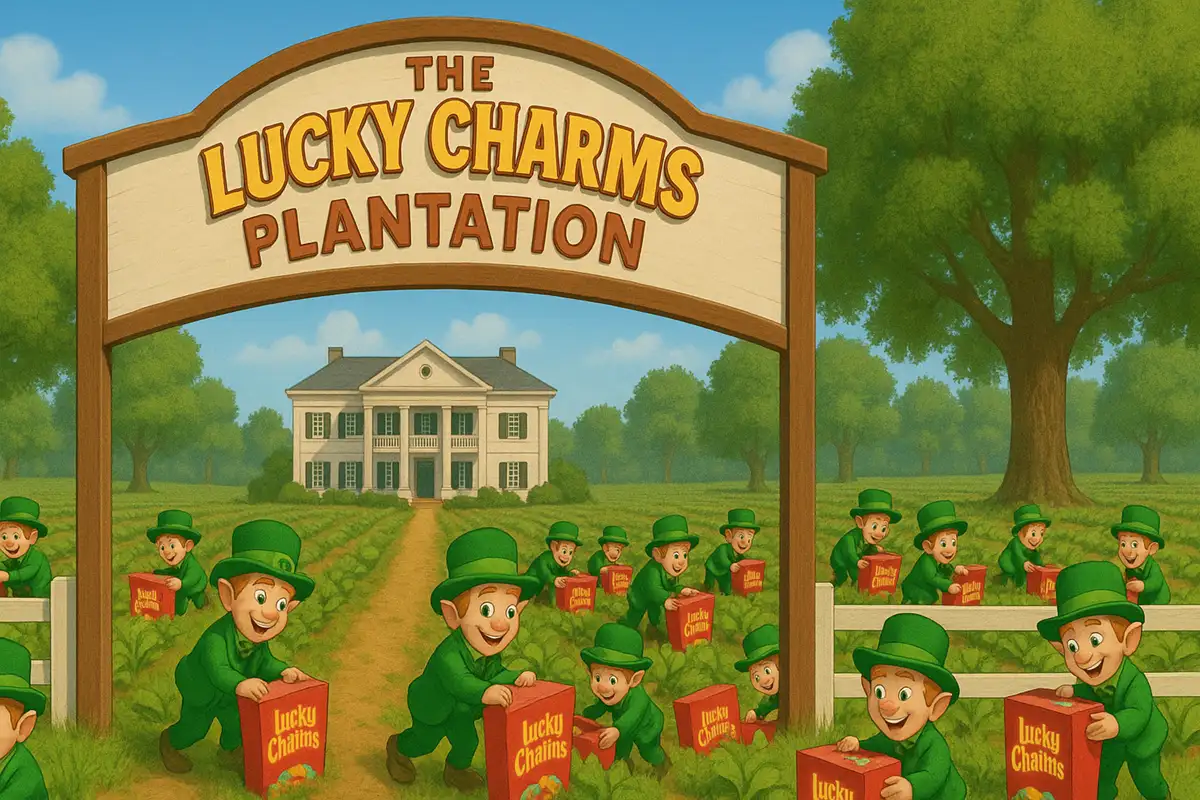

The digital propagation relies on easily digestible formats, primarily “memes,” which serve as quick, impactful vectors for the pseudohistorical claims. These digital artifacts frequently employ intentionally fabricated or misleading visuals to bolster the narrative’s emotional appeal. Examples include using photographs of Holocaust victims or 20th-century child laborers and falsely labeling them as “Irish slaves,” or employing images of modern Dutch children on a beach and claiming they are historical Irish victims. The use of dog-whistle images, such as the Confederate battle flag alongside the narrative, further reveals the racist intent underlying the disinformation.

This digital success highlights a symbiotic relationship between print and digital media. The popular books of the early 2000s offered the necessary, albeit false, historical citation, which the online environment then stripped of any remaining academic nuance, simplifying the message into an absolute equivalence designed for viral distribution.

Identifying the Perpetrators and Political Function

The primary groups responsible for propagating the Irish slaves myth are explicitly ideological: White Nationalists, Neo-Nazis, Neo-Confederates, and racist trolls. These groups, often operating outside Ireland in former white settler colonies like the US and Australia, weaponize the narrative for clear political purposes.

The central political objective is to minimize the historical singularity and devastating impact of hereditary chattel slavery on Africans and their descendants. The myth attempts to “create false equivalence between the Atlantic slave trade and the phenomenon of indentured Irish labour” to argue that slavery was not exclusively race-based and, therefore, contemporary racism is unjustified or exaggerated.

This narrative is explicitly deployed to “deny racism against African Americans” or claim they are “too vocal in seeking justice for historical grievances”. The common phrase adopted by these groups, “The Irish were slaves, too,” functions as a calculated strategy to “derail discussions about the legacy of slavery or ongoing anti-black racism,” particularly targeting movements like Black Lives Matter.

The narrative finds widespread secondary acceptance among broader internet users because it provides a psychologically convenient framework. The belief that white people were also historical victims of chattel slavery can function to release white individuals from contemporary guilt regarding the legacy of slavery, thereby furthering racial separation and deflecting demands for racial justice. The myth successfully exploits existing “Irish narratives of victimhood” within the Irish diaspora, twisting a legitimate history of forced labor and British colonial oppression into a comparison that specifically serves anti-Black political sentiment. The myth is thus a successful political obfuscation strategy, allowing opponents of racial justice to claim victimhood while minimizing historical complicity.

VI. Counter-Narratives and Historical Responsibility

The pervasive nature of the Irish slaves myth has necessitated a forceful and unified response from the academic community, which views the narrative as a threat to historical integrity and social discourse.

Academic and Journalistic Debunking Efforts

The academic consensus against the myth is firm and explicit. Historians routinely condemn the narrative as “fringe pseudohistorical” and “racist ahistorical propaganda”. In 2016, a critical turning point occurred when over 80 historians and academics, including senior Irish historians, co-signed an open letter urging news sites to remove articles that perpetuated the myth. This letter explicitly stated that the authors behind the myth sought “to belittle the suffering visited on black slaves”.

This academic intervention has prompted several media corrections. Sites that had previously published articles citing the flawed historical accounts, such as Scientific American and the Irish-American news website IrishCentral, were compelled to revise their content or publish op-eds clarifying that the Irish experience did not mirror the “extent or level of centuries-long degradation that African slaves went through”. Historians emphasize the necessity of constantly correcting the popular misuse of the term “slavery” in discourse to prevent the deliberate fallacy from becoming a benign, assumed historical fact.

Addressing Irish Collusion in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

An essential part of the historical counter-narrative involves moving beyond the simplified victimhood framework to acknowledge the complexity of Ireland’s relationship with the British Atlantic empire and the transatlantic slave trade. The persistence of the Irish victimhood narrative often serves to “hide the facts around Irish involvement” in the slave economy.

Historical records confirm that, far from being solely victims, many Irish individuals were active participants in the structures of racial slavery. Irish merchants developed extensive networks throughout the British Empire and accumulated wealth based on the trade and labor of enslaved Africans, particularly in the West Indies and the U.S. South. As documented, some Catholic Irish migrants successfully integrated into the Caribbean planter class by acquiring “enslaved Africans”. Furthermore, the reputation of Irish overseers in the Antebellum South as being exceptionally brutal towards enslaved African populations provides concrete evidence of Irish collusion with, and participation in, the violence inherent in the chattel slavery system.

The accurate historical account thus reveals a spectrum of experiences, from brutal forced labor suffered by the Irish poor to active participation in the enslavement of Africans by the Irish elite and successful migrants. This complexity is crucial for understanding that the myth operates as a strategy of historical simplification and political deflection.

VII. Conclusion: Synthesizing Historical Rigor and Contemporary Responsibility

The detailed analysis of colonial labor systems, demographic data, and the origins of the “Irish slaves myth” confirms the user’s initial premise: the Irish in the Americas and the Caribbean were overwhelmingly indentured servants or involuntary transportees, not chattel slaves, and the English comprised the largest contingent of European indentured laborers.

The historical record confirms an absolute legal distinction between indentured servitude, which was finite, non-hereditary, and afforded the laborer limited rights as an English subject, and chattel slavery, which was permanent, hereditary, and defined the individual as property (chattel) with no legal personality. The severity of the indentured experience, while often inhumane, cannot be equated with the institutionalized, perpetual, and racialized dehumanization that underpinned African chattel slavery.

The myth did not emerge from objective historical discovery but was engineered through sensationalist, non-academic print publications in the early 2000s that deliberately conflated these distinct legal statuses. Its subsequent rapid and sustained digital proliferation, primarily through social media memes since the 1990s, is a calculated ideological strategy. The primary propagators—white nationalists and Neo-Confederates—deploy the myth specifically to minimize the historical injustice of African chattel slavery, create a false equivalence of suffering, and undermine contemporary racial justice movements, such as Black Lives Matter.

For historians, journalists, and public intellectuals, the responsibility remains to emphasize that the legal and institutional codification of race-based, hereditary chattel slavery against Africans represents a unique historical atrocity, fundamentally separate from the harsh but legally finite bonded labor experienced by European indentured servants. Continued rigorous historical education is necessary to counter this resilient form of digital disinformation and prevent the calculated weaponization of suffering for contemporary political advantage.

Myth & Debunking

- Irish Slaves Myth – Wikipedia

Overview of the false narrative equating Irish indentured servitude with African slavery. - Irish People in the Caribbean Were Not Enslaved – The Guardian

Article explaining the distinction between forced labor and chattel slavery. - Black Lives Matter and the Irish Slave Myth – Al Jazeera

How the myth is misused to undermine discussions of racism and slavery. - Slaves to a Myth – UCSD Thesis

Academic study on Irish indentured servitude, African slavery, and white nationalist propaganda. - Review of “Irish Slaves” Meme Numbers – Liam Hogan

Breakdown of false statistics used in viral claims. - Contesting “White Slavery” in the Caribbean – Brill

Scholarly article examining distortions of history. - How the “Irish Slaves” Myth Became a Racist Meme – SPLC

Explains how extremists weaponize the myth online. - The Irish Slaves Meme – Leiden University Thesis

Research into digital archiving and the spread of the myth. - Stop Saying the Irish Were Slaves Too – The Quinnipiac Chronicle

Opinion piece urging correction of the myth. - Debunking the Imagery of the “Irish Slaves” Meme – Liam Hogan

Examination of manipulated images used to spread the myth. - No, the Irish Were Not Slaves – Pacific Standard

Journalistic rebuttal to misinformation around Irish history. - AP Fact Check: Irish “Slavery” a St. Patrick’s Day Myth – AP News

Quick myth-busting for a common holiday claim.

Indentured Servitude & Labor Systems

- Slavery vs Servitude – Shirley-Eustis House

Museum resource clarifying key differences between the two. - Everything About Indentured Servitude – Findmypast

Genealogical context for European indentured workers. - Indentured Servants in the U.S. – PBS

Public television feature on servitude in America. - New World Labor Systems – College of Charleston

Exhibit on indentured Europeans in the Atlantic world. - Irish Indentured Servants – Wikipedia

Encyclopedia entry on Irish workers in colonial systems. - Indentured Servitude in Colonial America – Oxford RE

Academic overview of the institution. - Indentured Servants in Colonial Virginia – Encyclopedia Virginia

Regional perspective on indentured labor.

Slavery, Law & Empire

- Origins of the Transatlantic Slave Trade – EJI

Report outlining the history of African enslavement. - Barbados Slave Code – Wikipedia

Legal foundation for race-based slavery in the Caribbean. - Colonial Authority (1600–1775) – Understanding Race

Educational overview of colonial governance structures. - Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery (Review) – Project MUSE

Review essay on Irish connections to slavery. - Ireland, Slavery and the Caribbean – Journal of Modern History

Book review exploring intersections of Irish and Caribbean slavery. - Irish Overseers in the Antebellum U.S. South – Cambridge

Historical study of Irish roles in plantation management. - Re-working the Slave Narrative – OpenEdition Books

Literary analysis of fictionalized Irish indentured stories. - Trinity College Reckons with Slavery Links – The Guardian

Modern reckoning with Ireland’s role in empire and slavery.

Popular History & Misinterpretations

- White Cargo – Barnes & Noble

Controversial book accused of overstating “white slavery.” - Reviewing the Fallout from “White Cargo” – Liam Hogan

Critical examination of the book’s flaws and influence.

Miscellaneous

- Kate McCafferty – University at Albany

Author archive with references to Irish and slavery topics.