AIM Leadership: Voices of Defiance

The American Indian Movement emerged in Minneapolis in 1968 amid police brutality, systemic poverty, and broken promises. Its leaders — Dennis Banks, Russell Means, John Trudell, and Leonard Peltier — embodied different dimensions of resistance.

- Dennis Banks (Ojibwe) was the strategist. A Marine veteran and co-founder of AIM, he organized patrols against police harassment and then expanded AIM into a national force. Banks helped lead the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties caravan, which culminated in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters in Washington, D.C., where activists demanded recognition of treaty rights. He later became one of the central figures at Wounded Knee.

- Russell Means (Oglala Lakota) became AIM’s fiery orator and media symbol. His dramatic presence and unapologetic rhetoric brought AIM visibility during actions at Mount Rushmore and Wounded Knee. Means often clashed with U.S. officials and the press, but his charisma galvanized Indigenous youth who saw in him an unflinching defender of sovereignty.

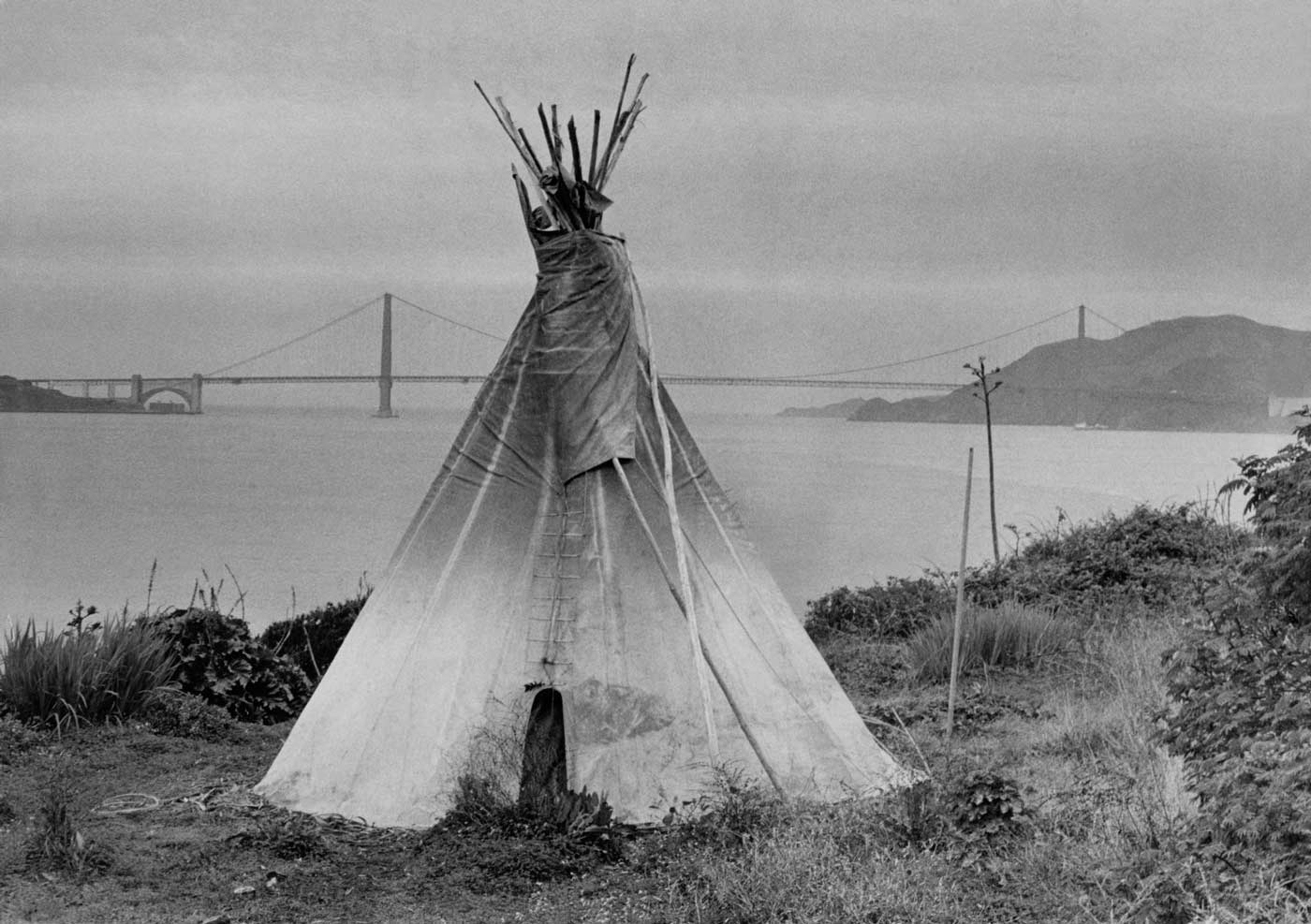

- John Trudell (Santee Dakota) was AIM’s philosopher and voice. Broadcasting from “Radio Free Alcatraz” during the 1969–71 occupation of Alcatraz Island, he framed Indigenous resistance in global terms. As AIM’s national chairman from 1973, he argued that cultural survival was political survival. After his wife, three children, and mother-in-law died in a suspicious house fire in 1979 — widely suspected to be linked to federal surveillance — Trudell reinvented himself as a poet and activist, carrying AIM’s spirit into art.

- Leonard Peltier (Turtle Mountain Chippewa/Lakota) represented AIM’s warrior element. A skilled organizer in local communities, he traveled widely to support embattled tribes. His imprisonment after the 1975 Pine Ridge shootout turned him into the most enduring symbol of AIM’s clash with the federal government.

Together, these leaders balanced grassroots activism, spiritual grounding, militant protest, and international advocacy. They defined AIM’s identity not only as a movement for Native rights, but as a movement of sovereignty and survival.

The 1973 Wounded Knee Occupation

By 1973, tensions on Pine Ridge Reservation had reached a breaking point. Tribal chairman Dick Wilson, accused of nepotism, financial corruption, and abuse of power, maintained his rule with federal support. When Wesley Bad Heart Bull, a young Lakota man, was killed by a white man who received only a light sentence, frustration boiled over.

On February 27, 1973, AIM activists and Oglala traditionalists seized the town of Wounded Knee, site of the 1890 massacre where U.S. troops slaughtered some 300 Lakota. The choice was deliberate: they invoked historical memory to highlight the continuity of oppression. Their demands included Wilson’s removal, Senate hearings on treaty violations, and recognition of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which guaranteed the Lakota the Black Hills.

The occupation lasted 71 days. Federal forces — FBI agents, U.S. Marshals, and BIA police — encircled the town with armored vehicles, helicopters, and spotlights. Each night brought gunfire. Two Native activists, Frank Clearwater and Buddy Lamont, were killed, and a U.S. Marshal was gravely injured. Food and medical supplies ran low, but AIM held firm, supported by sympathetic churches, activists, and global media attention.

Although the siege ended in May with a negotiated settlement, the government quickly abandoned its promises. Instead, it unleashed a wave of indictments: 562 charges against AIM members, making Wounded Knee the most litigated event in U.S. history at the time. Almost all charges were dismissed due to prosecutorial misconduct, but the trials drained AIM financially and psychologically. Yet Wounded Knee transformed Indigenous activism, showing that Native nations could command international attention and resist on their own terms.

Pine Ridge Conflict and the GOONs

After Wounded Knee, Pine Ridge became the epicenter of AIM’s struggle. Chairman Wilson, determined to consolidate power, created the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs), a paramilitary squad armed and funded in part by federal money. The GOONs terrorized AIM supporters and traditionalists with impunity: homes were firebombed, families threatened, and dozens of AIM members were assassinated.

Between 1973 and 1976, more than 60 unsolved murders were recorded on Pine Ridge. The community called it a “Reign of Terror.” The FBI, present in unprecedented numbers, turned a blind eye to GOON violence while keeping AIM under constant surveillance. Informants infiltrated AIM chapters, sowing mistrust. The atmosphere was one of civil war, with the GOONs acting as a de facto tribal militia for Wilson’s administration, backed tacitly by federal agencies.

It was in this climate of violence and paranoia that the 1975 shootout at Oglala occurred, leading to Leonard Peltier’s long imprisonment.

Uranium Mining and AIM’s Resistance

The repression on Pine Ridge was not only about tribal politics — it was also about land and resources. The 1970s uranium boom had made the Black Hills and surrounding Badlands strategically vital. BIA documents leaked in 1972 showed that Wilson’s administration had quietly agreed to lease large tracts of reservation land for uranium exploration.

Uranium extraction threatened sacred sites and carried devastating health consequences, already visible in Navajo communities where miners suffered cancers and water supplies were poisoned. AIM leaders argued that the repression of traditionalists was linked directly to clearing the way for mining corporations.

In response, AIM expanded its activism into environmental defense. It helped form the Black Hills Alliance, bringing together Lakota traditionalists, ranchers, and environmentalists to resist uranium leases. At camps like Yellow Thunder (1978–80), AIM activists reclaimed land and built communal resistance sites, framing the struggle as one of sovereignty against both colonialism and ecological destruction. The uranium issue thus bound together treaty rights, human rights, and environmental justice — decades before such concepts became mainstream.

FBI Surveillance and Leonard Peltier

The FBI’s war on AIM was an extension of COINTELPRO, its counterintelligence program targeting radical groups from the Black Panthers to the antiwar movement. AIM was labeled an “internal security threat.” Tactics included infiltration, forged documents, disinformation campaigns, and legal harassment.

On June 26, 1975, two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, pursued AIM members near Oglala on Pine Ridge. A firefight broke out, leaving both agents and AIM member Joe Stuntz dead. The incident triggered one of the largest manhunts in FBI history. Two AIM members, Bob Robideau and Dino Butler, were acquitted of the agents’ deaths on self-defense grounds. Leonard Peltier, extradited from Canada on coerced testimony, was tried separately in 1977. His trial was riddled with irregularities: the prosecution withheld ballistics evidence, intimidated witnesses, and relied on false affidavits. Peltier was convicted and sentenced to two consecutive life terms.

For AIM, Peltier’s imprisonment became the embodiment of federal repression. Amnesty International later declared him a political prisoner, and calls for his clemency have come from Desmond Tutu, the Dalai Lama, and the European Parliament. For many Indigenous people, Peltier remains both a martyr and a living symbol of resistance.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

While AIM was battered by repression, its cultural and political impact was profound. It inspired Indigenous communities to reclaim identity, pride, and sovereignty. Survival Schools were established to teach Native languages, histories, and traditions denied in public schools. Ceremonies such as the Sun Dance experienced revival, symbolizing resilience.

Politically, AIM’s militancy forced the federal government to reckon with Native demands. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975) allowed tribes more control over their programs, while the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978) protected sacred practices long criminalized. AIM also internationalized Indigenous struggles, creating the International Indian Treaty Council (1974), which secured recognition for Indigenous peoples at the United Nations.

Culturally, AIM challenged stereotypes and fought racist mascots, laying groundwork for campaigns that continue today. Its spirit reverberated through later movements such as the Idle No More uprising in Canada and the Standing Rock resistance (2016) against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Though AIM itself fractured under pressure, its legacy endures as both inspiration and warning: inspiration for its courage and sovereignty, warning for the costs of confronting entrenched power.

Primary Sources

Encyclopedia of U.S. History – American Indian Movement

The Guardian – Obituary of Russell Means

Los Angeles Times (AP) – Obituary of Dennis Banks

Ward Churchill, “Death Squads in the U.S.: Confessions of a Govt. Terrorist” (Yale J. of Law & Liberation)

Bill of Rights Institute – “American Indian Activism and the Siege of Wounded Knee”

Progressive Magazine – “Remembering John Trudell”

History.com – “American Indian Movement (AIM)”

Censored News (Brenda Norrell) – “Buried in Time: BIA Documents…Pine Ridge Uranium”

Akwesasne Notes and AIM archives – contemporary reports from Wounded Knee (1973–1975)Amnesty International USA – Leonard Peltier clemency petition (2021)

In the Spirit of Crazy Horse by Peter Matthiessen – background on Pine Ridge and Peltier case

Additional References

[PDF] Death Squads in the United States: Confessions of a Government…

Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against the Black…

[PDF] COINTELPRO: The Untold American Story

Leonard Peltier – Wikipedia

Making Invisible Histories Visible / The American Indian Movement…

American Indian Movement Interview | AIRC | Arts & Sciences | William & Mary

Leonard Peltier and the Indian struggle for freedom