Executive Summary: The Paradox of Cassius Marcellus Clay

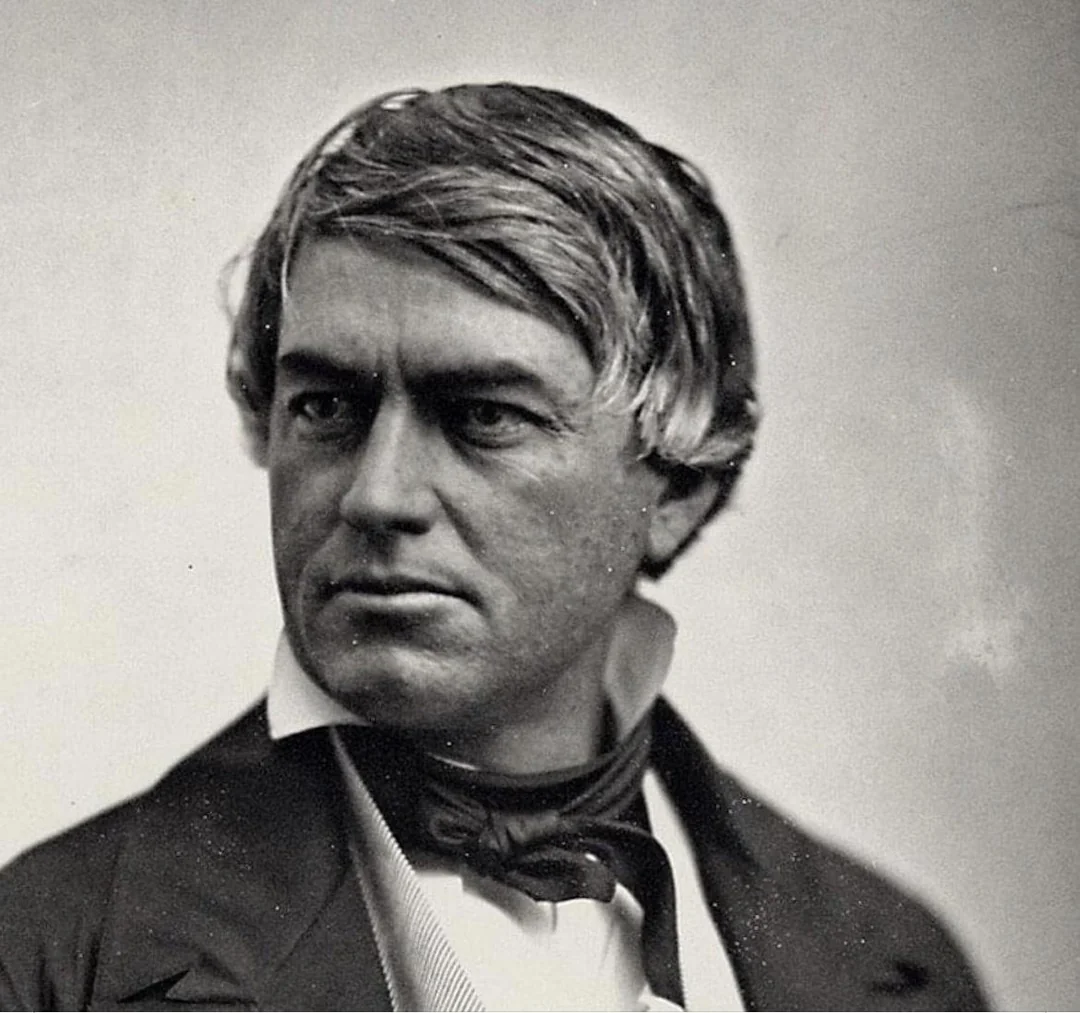

Cassius Marcellus Clay (1810–1903) was a figure of profound paradox who defied easy categorization. Born into the wealthy, slave-owning planter aristocracy of Kentucky, a state deeply entrenched in the institution of slavery, he would become one of the most visible and vocal anti-slavery crusaders in the United States. His fame, or infamy, was built upon a willingness to defend his convictions through violence, a pugilistic nature that earned him both the admiration of northern abolitionists and the violent enmity of his fellow Southerners. This readiness to engage in physical confrontation, often with a Bowie knife and pistols, became a defining characteristic of his public life.

Clay’s contributions to American history extended beyond his personal confrontations. He played a significant role in politics, serving three terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives. In 1845, he founded his own anti-slavery newspaper,

The True American, in the heart of the slaveholding South, an act of defiance that cemented his reputation. He was a founding member of the Republican Party in Kentucky and a friend and political ally of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln appointed him as the U.S. Minister to Russia, a diplomatic post he held from 1861 to 1862 and again from 1863 to 1869. In this role, he was instrumental in securing Russian support for the Union, a move that helped deter foreign intervention during the Civil War.

Despite his heroic public image, a comprehensive examination of Clay’s life reveals a more complex and at times flawed figure. His anti-slavery motivations were rooted as much in a pragmatic economic analysis of “free labor” as in moral conviction. His later life was marked by political shifts, eccentricity, and personal controversies, including a highly publicized divorce and his marriage to a teenager. The final assessment of his legacy is therefore nuanced: he was a crucial pioneer who challenged the system from within, but his actions and beliefs were far from perfect, a reality encapsulated in the later rejection of his name by the famous boxer Muhammad Ali.

Introduction: The Pugilistic Politician

On a summer day in 1843, at a political debate in Kentucky, a hired gunman named Sam Brown attempted to assassinate Cassius Marcellus Clay. Brown drew a revolver and shot Clay in the chest at close range. The attack seemed certain to be fatal, but at that precise moment, Clay had drawn his ever-present Bowie knife, and the bullet struck its silver scabbard, stopping short of his heart and saving his life. Despite being wounded and shocked, the formidable Clay did not flee. He immediately attacked the gunman with the very knife that had protected him, severely wounding Brown before tackling him and throwing him over an embankment.

This dramatic incident, which earned him a charge of mayhem even after he was acquitted, perfectly encapsulates the central paradox of Clay’s life. He was a man of the South—the son of a wealthy planter and enslaver from a large and influential political family —who became one of the institution’s most defiant and violent adversaries. His courage and willingness to fight earned him a fearsome reputation as a “rebel and a fighter”. He was a man of wealth who challenged the very system that created it and a supposed abolitionist whose views were far more complex than the simple label suggests. The story of Cassius Marcellus Clay is not merely a chronicle of an abolitionist’s struggles but an exploration of a complex individual whose life mirrored the growing ideological conflict that would tear the United States apart in the mid-19th century.

Part I: The Genesis of a Southern Emancipationist

Privilege and Family Roots

Cassius Marcellus Clay was born in 1810 into immense privilege in Madison County, Kentucky. His father, Green Clay, was one of the state’s wealthiest planters and a prominent enslaver and politician. The family was a powerful political dynasty, distant cousins to Henry Clay, the influential politician and statesman. Young Cassius grew up surrounded by luxury and affluence. He was educated at Transylvania University before attending Yale College, a move that would prove to be a pivotal turning point in his life.

The Spark at Yale

While at Yale, Clay’s worldview was fundamentally challenged by a public address by William Lloyd Garrison, a leading figure of the radical abolitionist movement. Garrison’s impassioned arguments for the immediate and unconditional emancipation of enslaved people had a profound impact on the young man from Kentucky. Clay later recalled that Garrison’s words were “as water is to a thirsty wayfarer,” suggesting a deep and immediate resonance with his conscience. This encounter provided the initial impetus for his anti-slavery activism, sparking a path that would put him at odds with his family, his class, and the entire Southern way of life.

A Calculated Crusade: The Economic Rationale for Free Labor

While Garrison’s lecture may have been the moral spark, the continuous motivation for Clay’s anti-slavery views was not the purely moral outrage of a typical abolitionist, but a pragmatic economic analysis he developed during his time in the Northeast. This perspective on his motivations is crucial for a complete understanding of his work. While the user’s initial query suggests a figure driven by sheer moral heroism, the available evidence presents a more complex and perhaps less romanticized reality.

Clay observed the “free labor economy” of the North and saw a dynamic system where hard work and personal industry led to prosperity. He contrasted this with the agrarian, slave-based economy of the South, which he viewed as economically stagnant and unsustainable. His core argument was that slavery was not merely a moral evil but an institutional impediment to the progress and prosperity of white Americans. He contended that the institution of slavery, and the competition with unpaid labor, drove thousands of white Kentuckians to move to free states like Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, resulting in a smaller population, reduced tax base, and fewer public resources for his home state. He made his priorities explicit, stating that his sympathies were “for the white man—bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh—his industry, independence and comfort are the strength, the wealth, and the glory of the State”.

This perspective forces a re-evaluation of the label “abolitionist.” In the 19th century, true abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison advocated for the immediate, unconditional end of slavery on moral grounds. Clay, however, was an incrementalist who sought gradual, state-level change, believing that this was the most pragmatic path to success. He publicly distanced himself from the term, stating in an 1840 campaign that he was “no emancipationist, far less an ‘abolitionist,’” and that his goal was a “safe, slow, and undefined end” to the institution. This nuanced view reveals that Clay’s journey was not a simple moral conversion but a complex evolution rooted in a mix of moral feeling and pragmatic, and at times racially-motivated, beliefs about economic progress. After returning to Kentucky, he took his first steps in politics by serving three terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives and working to retain the state’s ban on the importation of slaves.

Part II: The True American: A Fortress of Free Speech

Founding a Voice in Enemy Territory

In June 1845, Cassius Marcellus Clay founded an anti-slavery newspaper, The True American, in Lexington, Kentucky. This act was a deliberate and provocative challenge to the institution of slavery. The newspaper’s office was strategically located just one block away from one of the largest slave markets in the United States, a defiant gesture that left no doubt as to Clay’s intent. Through his paper, Clay not only advanced the cause of emancipation but also published material on labor, agriculture, and commerce, consistent with his broader economic arguments against slavery.

A Fortress of Free Speech

Clay understood that his venture would be met with fierce and violent opposition. He had already survived one assassination attempt, and he prepared for the inevitable confrontation with a strategic and comprehensive plan that has since become a part of his legend. Clay fortified his newspaper office, turning it into a fortress of free speech. The street doors were lined with sheet iron to make them fireproof, and at the top of the stairway, he installed two brass cannons loaded with musket balls and old nails. He kept a large supply of rifles and muskets on hand and, in a final act of desperate defiance, placed two barrels of black powder in a corner of his editorial office. His staff was instructed that if a mob ever managed to overrun the defenses and reach the second floor, they were to escape through a rooftop hatch. Clay, however, would remain behind to drop a match into the powder and blow the entire building to fragments, demolishing himself, his office, and all the assailants within it. This plan, while never executed, perfectly exemplifies the way Clay met life’s challenges.

The Mob and the Fever

Within a month of its publication, The True American was receiving daily death threats. A group of pro-slavery citizens, calling themselves the “Committee of Sixty,” was formed with the express purpose of shutting down the paper. The narrative of a heroic stand against the mob, however, is not what transpired. The sources reveal a crucial, and perhaps less heroic, detail: the mob did not storm a fully defended fortress with Clay at the helm. Instead, they waited until he was incapacitated with a fever, or “typhoid fever” as some sources suggest. This timing was a calculated strategy, as it allowed the mob to act with a court injunction and seize Clay’s printing press without engaging in what “surely would have been a deadly counterattack”.

After dismantling his press, the mob shipped the equipment to Cincinnati, Ohio. While this was a victory for the pro-slavery faction, it had a different effect on the national stage. Clay, an advocate for free speech, simply continued publishing the paper from Cincinnati for the next two years, distributing it back in Kentucky. This act of persistence transformed him from a local agitator into a “hero in the anti-slavery movement” and a martyr for the cause of a free press.

Part III: The Brawler, the Diplomat, and the Lincoln Connection

The Bowie Knife Abolitionist

Clay’s reputation as a “rebel and a fighter” was not limited to his newspaper defense plans; it was a cornerstone of his political career. He became accustomed to carrying two pistols and a knife for protection, and his willingness to engage in physical combat was well-documented. Below are some of his most notable violent encounters.

1843

Sam Brown (hired gunman)

Location: Political debate

Description of Attack: Shot in the chest

Weapons Used: Revolver, Bowie knife

Outcome for Clay: Bullet hit his Bowie knife; survived with a wound

Outcome for Opponent(s): Severely wounded, lost an eye, nose, and possibly an ear; thrown over an embankment

1849

The six Turner brothers

Location: Foxtown, Kentucky

Description of Attack: Beaten, stabbed, and shot at after a speech

Weapons Used: Knives, clubs, pistol, Bowie knife

Outcome for Clay: Wounded, stabbed in the lung, breastbone severed; survived

Outcome for Opponent(s): One brother, Cyrus Turner, was killed with a Bowie knife

The attack by Sam Brown in 1843 was an iconic moment in his life, where the bullet was famously stopped by the Bowie knife he had just drawn. After the 1849 attack by the six Turner brothers, he fought them all off, killing one of them, Cyrus Turner, with his Bowie knife. These incidents were not isolated events but defined his persona, making him a figure to be both feared and respected.

An Uneasy Alliance with Lincoln

Clay’s political career and reputation led him to the national stage. He was a founder of the Republican Party in Kentucky and became a friend of Abraham Lincoln, supporting him for the presidency in 1860. At the 1860 Republican National Convention, Clay even delivered an enthusiastic speech nominating Lincoln, and he was a runner-up for the vice-presidential nomination.

The relationship between the two men, however, was a complex and pragmatic one. Lincoln valued Clay as a political ally but was wary of his volatile temperament, at one point reportedly calling him a man with “a great deal of conceit and very little sense”. When Clay sought a cabinet position, William Seward and others advised Lincoln against it, arguing that his appointment would “constitute a declaration of war on the South”. As a result, Clay was appointed as the U.S. Minister to Russia in April 1861. This appointment was not his first choice, as he had initially objected to Spain and was rejected for his preferred posts in England or France.

Clay’s diplomatic service, however, proved to be of monumental importance. During his two terms as U.S. Minister to Russia, from 1861 to 1862 and again from 1863 to 1869, he was instrumental in securing Russian support for the Union. Tsar Alexander II, who had freed 23 million serfs in 1861, was sympathetic to the Union cause. Clay used his influence to strengthen this bond, which resulted in Russia sending its Atlantic and Pacific naval fleets to U.S. ports as a show of solidarity. This move may have helped to deter Britain and France from intervening in the war on the side of the Confederacy, a critical factor in the Union’s victory. Clay’s diplomatic skills also proved useful in the negotiation of the Alaskan purchase in 1867.

He returned from Russia briefly in 1862 to accept a commission from Lincoln as a major general in the Union Army. However, he publicly refused to accept the position unless Lincoln agreed to emancipate the enslaved people under Confederate control. While Lincoln had his own reasons for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation later that year, Clay’s public stance was a powerful push that aligned with the later, more definitive action.

1835–1841

Kentucky House of Representatives

Serves three terms, works to retain Kentucky’s ban on the importation of slaves

1843

Political opponent/abolitionist

Survives assassination attempt by Sam Brown at a political debate; seriously wounds attacker with a Bowie knife

1845–1847

Newspaper publisher

Founds The True American in Lexington, Kentucky; fortifies office with cannons; press seized by a mob while he is ill

1849

Political activist

Fights off six attackers at a speech, killing one (Cyrus Turner) with his Bowie knife

1854

Founder of Republican Party

Becomes a leading figure and founding member of the Republican Party in Kentucky

1860

Political ally of Lincoln

Supports Abraham Lincoln for President; briefly runs for Vice President at the Republican National Convention

1861–1862

U.S. Minister to Russia

Appointed by Lincoln; works to gain Russian support for the Union

1862

Major General, Union Army

Recalled from Russia; publicly refuses a commission unless Lincoln agrees to emancipation

1863–1869

U.S. Minister to Russia

Reappointed by Lincoln; continues to secure Russian support; involved in the negotiation of the Alaskan purchase in 1867

Part IV: Legacy and Final Years

Post-War Controversies and Eccentricity

Following the Civil War, Clay’s life took a series of tumultuous turns. He left the Republican Party in 1869, disapproving of the Radicals’ Reconstruction policies, and later supported the Liberal Republican and Democratic parties. His later years were also marked by increasing eccentricity and paranoia. He continued to carry two pistols and a knife for protection, and he even installed a cannon to protect his home and office, Whitehall.

His personal life became a source of scandal. In 1878, after 45 years of marriage, he divorced his wife, Mary Jane Warfield Clay, claiming abandonment. This move was a result of his long-standing “marital infidelities,” which his wife would no longer tolerate. Perhaps most controversially, in 1894, at the age of 84, Clay married Dora Richardson, a 15-year-old. He also adopted a son, Henry Launey Clay, believed to be his illegitimate child from a relationship while in Russia. These final acts cemented his reputation as a volatile and unpredictable figure, whose personal life overshadowed his earlier political and military accomplishments. He died on July 22, 1903, of “general exhaustion”.

An Enduring and Contested Name

One of the most enduring, and often misunderstood, connections in Clay’s legacy is his link to the 20th-century boxing icon, Muhammad Ali. The boxer was born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., named after his father, who was named after the abolitionist. However, in 1964, after converting to Islam, the boxer famously rejected his birth name, calling it a “slave name”. His statement, “I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name—it means beloved of God, and I insist people use it when people speak to me,” was a profound act of self-determination.

Ali’s rejection of the name does not diminish the historical significance of the original Cassius Marcellus Clay; rather, it provides a critical lens through which to view his legacy. It highlights a fundamental difference between the white anti-slavery movement of the 19th century and the fight for racial justice and self-determination in the 20th century. While Clay put his body and wealth on the line to end the institution of slavery, his motivations were, in part, rooted in a desire for white economic and social progress. For Ali, the name itself was a symbol of an oppressive system that, even after abolition, denied Black Americans their full humanity and agency. The fact that the name of a white anti-slavery crusader could be considered a “slave name” by a Black man highlights the “messiness of White antiracist history” and the complex, often incomplete nature of liberation.

Conclusion: The Enduring Paradox

Cassius Marcellus Clay was a figure of contradiction whose life and legacy are far from simple. He was a Southern gentleman who defied the very foundations of his society, a statesman whose violent and eccentric behavior often threatened to derail his political career, and a so-called abolitionist whose motivations were more complex than a purely moral crusade. His willingness to use violence to protect his right to free speech and to challenge the institution of slavery from within the South was a rare and vital act of defiance. He was a pioneer in the anti-slavery movement, a founder of the Republican Party, a trusted, albeit volatile, advisor to Abraham Lincoln, and a diplomat who secured a crucial alliance for the Union.

His enduring fame rests on his defiant spirit—the image of a man who survived assassination attempts and fortified his newspaper office with a cannon. However, a full understanding of his life must also acknowledge his pragmatic and at times racially-motivated beliefs, his personal failings, and his later-life decline. He was a man of his time, whose actions helped to turn the tide of history, but whose legacy remains a complicated subject of study. He proved that opposition to slavery was possible, even in the heart of the slaveholding South, and his life, for all its flaws, remains a testament to the power of one individual’s unwavering conviction.

Wikipedia Articles

Government and Library Resources

- Clay, Cassius M. – Papers Of Abraham Lincoln

- The True American | Lexington Public Library

- Library of Congress – Minister to Russia Cassius Marcellus Clay

- Slavery as a Cause of the Civil War – Lincoln Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)

- Dedicated to Universal Liberty: Abolitionist Newspapers in Kentucky | UK Libraries

- Electronic Field Trip to White Hall Historic Site, Home of Cassius M. Clay

- Notable Visitors: Cassius M. Clay (1810-1903) – Mr. Lincoln’s White House

Historical Societies and Museums

- Cassius M. Clay – Richmond Cemetery – Richmond, KY

- Cassius Marcellus Clay – Kentucky Historical Society

- Cassius Marcellus Clay – Clay Family Society: Fellowship

- Myths & Misunderstandings: The North and Slavery Archives – American Civil War Museum

- White Hall State Historic Site, home of Cassius Marcellus Clay – Clio

Academic Sources

News and Media

- Cassius Marcellus Clay, The Maverick Politician Who Fought For…

- The Rage Of The Aged Lion – American Heritage

- Muhammad Ali originally named for ardent abolitionist and Yale alumnus Cassius Clay

- Guest columnist: Clay was Kentuckian at the Court of the Tsars | State-Journal

- Lincoln’s Forgotten Plan for Post-Confederate Texas – Texapedia

Educational and Social Justice Resources

- Cassius Marcellus Clay, abolitionist born – African American Registry

- 3 things we learned from Muhammad Ali #BlackHistoryMonth – Rumie

- Sufi Boxer Muhammad Ali’s last fight was against Extremism & Politicians’ Islamophobia

- Cassius Marcellus Clay – Cross Cultural Solidarity