Introduction

Paul Robeson was a quintessential 20th-century Renaissance man whose unparalleled talents as a scholar, athlete, artist, and activist were inextricably linked to his unyielding fight against global white supremacy. His career trajectory, particularly his expatriate success in England and his controversial embrace of the Soviet Union, was a direct response to the systemic racism that defined and ultimately sought to destroy him in his native United States. His confrontation with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was not merely a defense of his political beliefs but the culmination of a life spent challenging the legitimacy of a nation that celebrated his gifts while denying his humanity. A figure of immense talent and profound conviction, Robeson rose to global prominence as a two-time All-American football player, a Phi Beta Kappa scholar, a Columbia-educated lawyer, a pioneering actor on stage and screen, and a concert singer with a bass-baritone voice of legendary power and beauty. Yet, these extraordinary accomplishments were perpetually shadowed by the reality of Jim Crow America.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Robeson’s life, tracing the arc from his formative years, shaped by the legacy of a father who escaped slavery, to his emergence as an international star who found greater artistic and personal freedom abroad. It will examine the political awakening that transformed him from an artist into a revolutionary, his complex and fraught relationship with the Soviet Union and communism, and the brutal, systematic campaign of persecution by the U.S. government that sought to erase him from public memory. Through a detailed investigation of his careers, his activism, and his defiant 1956 testimony before HUAC, this analysis will demonstrate that every facet of Paul Robeson’s public life was a conscious act of resistance against a society that refused to recognize his full stature as a man. His story is not just that of a great artist but of an American titan whose legacy remains a powerful and unsettling testament to the price of uncompromising principle.

Part 1 – The Forging of a Renaissance Man (1898-1923)

The defiance and intellectual rigor that defined Paul Robeson’s later life were not spontaneous developments but were forged in the crucible of his early experiences. His character was a direct inheritance from a family legacy of resilience against the brutalities of slavery and a personal confrontation with the paradox of American society—a nation that offered the promise of meritocracy while simultaneously enforcing a violent racial hierarchy. His journey from a minister’s son in Princeton to a celebrated scholar-athlete at Rutgers and a disillusioned lawyer in New York established the foundational understanding that excellence alone was insufficient to overcome the systemic barriers of racism, a realization that would redirect his life’s course from the courtroom to the world stage.

A Father’s Legacy: Slavery, Ministry, and Principle

Paul Robeson’s bedrock principles were a direct inheritance from his father, the Reverend William Drew Robeson. Born into slavery in Martin County, North Carolina, in 1844, William escaped the plantation as a teenager in 1860, trekking north to Pennsylvania. During the Civil War, he worked as a laborer for the Union Army before pursuing an education, ultimately earning a divinity degree from Lincoln University, a historically Black college. This journey from bondage to intellectual and spiritual leadership provided a powerful example of self-emancipation and determination for his youngest son, Paul, who was born on April 9, 1898. His mother, Maria Louisa Bustill, came from a distinguished line of free Black abolitionist Quakers in Philadelphia, adding another layer of activist and intellectual heritage to the family.

By the time of Paul’s birth, William Robeson was the respected pastor of Princeton’s Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church. However, this position of authority was conditional. In 1901, a conflict with the church’s white financial sponsors, who judged Reverend Robeson “insufficiently servile,” led to his forced resignation. This event was a formative lesson for the young Paul, demonstrating that for a Black man, even one of great moral and intellectual stature, success and respect were contingent upon deference to white authority. Following this and the tragic death of his mother in a house fire when he was six, the family faced hardship, with his father taking on menial jobs before establishing a new A.M.E. Zion church in Westfield, New Jersey. Throughout, William Robeson, a master of oratory and English diction, instilled in his son a profound sense of discipline, a commitment to excellence, and an unwavering belief in the dignity of his people. Paul excelled at Somerville High School, where he was one of only a handful of Black students, earning accolades in debate, singing, and athletics despite facing racist taunts.

The Rutgers Phenom: Excellence in the Face of Hostility

In 1915, Robeson won a statewide academic scholarship to Rutgers College, becoming only the third African American to enroll at the institution and the only one at the time. His time at Rutgers was a showcase of extraordinary, multifaceted talent, but it was also a constant battle against racial hostility. His attempt to join the Scarlet Knights football team was met with brutal violence from his own prospective teammates, who in one scrimmage broke his nose and dislocated his shoulder in a clear attempt to drive him away. Heeding his father’s counsel to persevere, Robeson endured the abuse and made the team, going on to become one of the greatest players of his era. A towering figure at 6’3″ and over 200 pounds, he was a two-time consensus All-American end, hailed by legendary coach Walter Camp as the greatest end ever.

This athletic success, however, did not shield him from the indignities of Jim Crow. In his sophomore year, Rutgers benched him when Washington and Lee University, a Southern team, refused to take the field against a Black player. While he was the star of the university’s glee club, he was not permitted to travel with the group or attend post-performance social functions. These incidents starkly illustrated that his exceptional abilities were celebrated only when they did not fundamentally challenge the prevailing racial order.

Simultaneously, Robeson dominated academically and oratorically. He won the college oratorical contest four years in a row and maintained such high grades that he was inducted into the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa honor society in his junior year—one of only four students in his class to receive the honor. He was also selected for the elite Cap & Skull Honor Society, and in 1919, his classmates elected him class valedictorian. In his commencement oration, “The New Idealism,” he delivered an optimistic, somewhat conciliatory speech calling on the “favored race” to “clasp friendly hands” with their Black brethren. It was a vision of racial harmony he would later find untenable in the face of unyielding American racism. The pattern of his Rutgers years was clear: he could achieve perfection by every metric the institution valued, yet the institution itself would still subordinate his humanity to the prejudices of others.

A Law Career Derailed: The Limits of the System

After graduating from Rutgers, Robeson moved to Harlem and enrolled at Columbia Law School in 1920. To finance his education, he drew on his athletic fame, playing professional football on weekends for teams in the American Professional Football Association (a precursor to the NFL), including the Akron Pros alongside fellow Black pioneer Fritz Pollard, and the Milwaukee Badgers. He earned his LL.B. degree in 1923 and, through a Rutgers connection, secured a position at the New York law firm of Stotesbury and Miner.

His tenure in the legal profession was brief and ended with a stark, humiliating incident that crystallized the systemic racism he faced. A white stenographer at the firm refused to take dictation from him, stating plainly that she would not take orders from a Black man. While the firm’s head, Louis Stotesbury, was sympathetic, he was also candid, cautioning Robeson that the prejudice was pervasive and that white clients would likely never accept being represented by a Black attorney. This moment was a profound disillusionment. He had followed the prescribed path to success—excelling at a top university and graduating from an elite law school—only to be blocked by the most basic and intractable racism. The experience demonstrated that the legal system, ostensibly a bastion of justice, was as deeply infected by prejudice as any other part of American society.

This realization prompted a strategic pivot. Encouraged by his wife, Eslanda “Essie” Goode, whom he had married in 1921, Robeson abandoned law for a full-time career in the arts, where he had already begun to moonlight in local productions. His decision was not an escape from the fight but a change in venue and tactics. He famously told the

New York Herald Tribune, “As an actor, I think I have less to buck against than as a lawyer”. This was a calculated assessment of power. In the legal world, his success was contingent on the cooperation of a prejudiced infrastructure of secretaries, partners, and clients. On the stage, while racism was still a formidable obstacle, his primary assets were his own voice, presence, and talent—tools over which he had direct control. He chose the arena where his individual genius could more forcefully challenge the stereotypes that underpinned the very system that had rejected him.

Part 2 – The Artist on Two Continents (1924-1939)

Paul Robeson’s artistic career in the 1920s and 1930s unfolded across two vastly different cultural landscapes: the racially stratified world of American theater and the more socially fluid, politically charged environment of London. In the United States, he achieved stardom but was constrained by the limited and often stereotypical roles available to Black actors. In England, he found not only greater professional opportunities that allowed him to tackle iconic roles like Othello, but also an international community of anti-colonial and socialist thinkers who catalyzed his political awakening. This transatlantic experience was pivotal, transforming him from an artist who experienced racism into an activist who understood its global, systemic nature.

2.1 From Harlem to Broadway: A Constrained Brilliance

Robeson’s professional artistic career was launched from the epicenter of the Harlem Renaissance. He became a prominent figure in this cultural movement, working with the progressive Provincetown Players, a Greenwich Village theater group that had staged his first benefit performance while he was in law school. His breakthrough came in 1924 with leading roles in two plays by Eugene O’Neill:

All God’s Chillun Got Wings and a revival of The Emperor Jones.

His performances were immediately acclaimed, but they were also fraught with controversy. All God’s Chillun Got Wings, which depicted an interracial marriage, provoked a national uproar and death threats from groups like the Ku Klux Klan, who threatened to bomb the theater. The play was the first on the American stage to feature a Black man in a leading role opposite a white woman, a direct challenge to the nation’s deepest racial taboos. Robeson also faced criticism from the Black press for his role as Brutus Jones in

The Emperor Jones, a tragic figure they felt pandered to negative stereotypes of African Americans. Robeson defended his choice, arguing that portraying a complex, tragic Black protagonist was a significant advancement from the one-dimensional “Sambo” roles traditionally assigned to Black actors and a necessary step toward more authentic representation.

THE PAUL ROBESON COLLECTION

These songs are taken from six Victor 10″ 78s. The recordings date from 1935-1941. Tracks 1-4 come from Porgy and Bess. Hearing Summertime sung by a bass baritone puts a different spin on it. Transfers from the original 78s by Bob Varney. archive.org

Concurrent with his stage success, Robeson launched a revolutionary concert career. Teaming up with the accomplished pianist and arranger Lawrence Brown, he began performing programs composed entirely of African American spirituals and folk songs. In April 1925, their debut concert in Greenwich Village was a sensation, prompting sixteen encores. This was a radical act of cultural reclamation. Robeson presented these songs not as quaint folk curiosities but as profound artistic expressions of a people’s history and struggle. He described them as “not songs of defeat,” but as the very music that sustained Black people through their trials. He was the first artist to present entire concerts of Black spirituals to white audiences, elevating the genre to the level of classical art song and establishing himself as one of the most popular concert singers of his time.

“A Veritable Othello of Battle”: Finding Freedom in London

In the late 1920s, Robeson relocated to London, where he and his wife Essie would live for over a decade. While Britain was not free of racism, the social and professional climate offered a degree of freedom and opportunity unavailable in the United States. The “color-bar” was less formally institutionalized than American Jim Crow, and Robeson was shocked on the rare occasion he encountered it, such as when he was initially denied service at London’s Savoy Hotel in 1929—an incident that would have been unremarkable in America.

This more tolerant environment translated into greater artistic possibilities. In 1928, he starred in the London premiere of the musical Show Boat at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. His powerful portrayal of Joe and his definitive rendition of “Ol’ Man River” made him an overnight sensation in Britain. The song, which Jerome Kern reportedly wrote with Robeson’s “organ-like tones” in mind, became his global trademark. His success was so immense that he was invited for a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace.

The pinnacle of his London stage career came in 1930, when he played Othello at the Savoy Theatre opposite Peggy Ashcroft. He was the first Black actor to take on the role in London in nearly a century, since the pioneering Ira Aldridge in the 1820s. The production was a major cultural event, and despite a flawed staging and some racist backlash to a Black man kissing a white actress on stage, Robeson’s performance was largely acclaimed, earning him twenty curtain calls on one night. The critical reception was mixed and often filtered through a racial lens, with some critics praising his “natural” ability in a backhanded way, suggesting an untutored, primal quality. Nevertheless, the role cemented his status as a serious classical actor. This experience stood in stark contrast to his later, record-breaking 1943-44 Broadway run of

Othello, which was met with near-universal critical praise and ran for 296 performances, a record for a Shakespearean play on Broadway that still stands.

FIlm Career

Paul Robeson made his film debut at the age of 27 in Body and Soul (1925), a race film produced, written, directed, and distributed by Oscar Micheaux, playing the dual role of Jenkins and Sylvester. As part of the agreement to star in the film, Robeson received a $100 per week salary plus three percent of the gross after the first $40,000 in receipts.

In 1925 Paul delivered his first singing recital and also made his film debut starring in Body and Soul (1925), a rather murky melodrama that nevertheless was ahead of its time in its depictions of black characters. Although Robeson played a scurrilous, corrupt clergyman who takes advantage of his own people, his dynamic personality managed to shine through.

This film, however, was controversial from the start. The original version of Body and Soul was a nine-reel production. When the filmmaker applied for an exhibition license from the Motion Picture Commission of the State of New York, it was denied approval on the grounds it would “tend to incite to crime” and was “immoral” and “sacrilegious”. Micheaux was forced to re-edit the film twice before the commission approved the film, which was reduced from nine to five reels.

The Emperor Jones

Of all Paul Robeson’s eleven starring film performances, by far his most iconic was his breakthrough in the big-screen adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (1933). He was already a legend for his stage incarnation of Brutus Jones, a Pullman porter who powers his way to the rule of a Caribbean island, but with this, his first sound-era film role, his regal image was married to his booming voice for eternity. With The Emperor Jones, Robeson became the first African-American leading man in mainstream movies.

FILMOGRAPHY

1925 – BODY AND SOUL

Directed by pioneering African-American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux, Body and Soul marked the screen debut of legendary performer Paul Robeson, who plays dual roles as both a corrupt preacher and his virtuous twin brother. The film tells the story of Reverend Isaiah T. Jenkins, actually an escaped convict masquerading as a minister, who exploits his congregation’s faith for personal gain.

1933 – The Emperor Jones

The narrative follows Jones as he evolves from an honest Pullman porter into a cunning manipulator who commits murder during a dice game, escapes from chain gang after killing a guard, and eventually arrives in Haiti. There, aligned with corrupt white trader Smithers (Dudley Digges), Jones exploits local superstitions to overthrow the existing ruler and install himself as emperor.

1936 – A Song of Freedom

The film tells the story of John Zinga (Robeson), a London dock worker with an extraordinary voice who becomes an overnight opera sensation. When Zinga discovers an ancient medallion that reveals his royal African heritage, he abandons his successful career to return to the island of Casanga, where he believes he is destined to rule and bring progress to his people.

1937 – BIG FELLA

Set in Marseilles, the film casts Robeson as Joe, a dock worker with a beautiful singing voice who becomes involved in searching for a missing English boy who has run away from his wealthy parents. The waterfront setting allows Robeson to perform several songs, including work songs, folk ballads, and popular tunes that showcase his remarkable vocal range.

1937 – Jericho

Jericho features Paul Robeson as Corporal Jericho Jackson, an American soldier in World War I who faces execution after being wrongly blamed for deaths during a troopship evacuation.

1937 – King Solomon’s Mines

This British adaptation of H. Rider Haggard’s adventure novel features Paul Robeson as Umbopa, an African chief who joins Allan Quartermain’s expedition to find the legendary diamond mines of King Solomon. Unlike previous and subsequent versions, this adaptation expanded Robeson’s role significantly, allowing him to sing several songs and present Umbopa as a dignified, intelligent character rather than a mere servant.

1942 – TALES OF MANHATTAN

Tales of Manhattan is a 1942 anthology film that follows a single tailcoat as it weaves through the lives of various owners in five distinct stories. The star-studded cast includes Rita Hayworth, Henry Fonda, Charles Laughton, and Edward G. Robinson. The film culminates in the tailcoat’s final journey to a poor sharecropper played by Paul Robeson, who uses it to buy new clothes for his community.

British Film Career

After facing significant racism in the United States, Robeson found more success in British cinema. He undertook the role of Bosambo in the movie Sanders of the River (1935), which he felt would render a realistic view of colonial African culture. Sanders of the River made Robeson an international movie star; but the stereotypical portrayal of a colonial African was seen as embarrassing to his stature as an artist and damaging to his reputation.

Despite this disappointment, Robeson continued working in British films. Song of Freedom is a 1936 British musical drama film directed by J. Elder Wills and starring Paul Robeson. Robeson was also given final-cut approval, an unprecedented option for an actor of any race. The film dealt with themes of African heritage and identity, with Robeson playing a London dockworker who discovers his royal African lineage.

The Proud Valley is a 1940 Ealing Studios film starring Paul Robeson. Filmed in the South Wales coalfield, the principal Welsh coal mining area, the film is about an African American seaman who joins a mining community. Years later, Robeson would remark that, of all his films, this was his favorite because it showed workers in a positive light.

Show Boat (1936)

Show Boat is a 1936 American romantic musical film directed by James Whale, based on the 1927 musical of the same name by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II. Robeson, for whom the role of Joe was actually written, had appeared in the show onstage in London in 1928 and in the Broadway revival of 1932.

Arguably the most famous rendition of the song, one that is still noted today, was sung by Robeson in James Whale’s classic 1936 film version of Show Boat. The film became one of Robeson’s most iconic performances, with his rendition of “Ol’ Man River” becoming his signature song.

Tales of Manhattan and End of Film Career

Tales of Manhattan was Robeson’s final attempt to work within Hollywood, after making only 12 movies and refusing lucrative film offers for over three years. The film proved to be deeply problematic for Robeson.

Although Robeson attempted to change some of the film’s content during production, in the end he found it “very offensive to my people. It makes the Negro childlike and innocent and is in the old plantation hallelujah shouter tradition … the same old story, the Negro singing his way to glory.”

Following its release, he held a press conference announcing that he would no longer act in Hollywood films because of the demeaning roles available to Black actors. Robeson also said he would gladly picket the film along with others who found the film offensive.

The Political Awakening in Exile

Robeson’s years in London were not just artistically formative; they were politically transformative. He later stated that he “discovered Africa in London”. Immersing himself in study, he enrolled at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, where he studied African languages, culture, and phonetics. He became deeply involved with the West African Students Union and forged lasting friendships with a generation of future anti-colonial leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. This intellectual journey solidified his Pan-Africanist consciousness and fused his artistic mission with a political one. He declared his central idea was “to be African,” an ideal he saw as eminently worth living and dying for.

His political evolution was also profoundly shaped by his connection to the British working class. In 1929, a chance encounter with a protest march of striking Welsh miners in London created a lifelong bond. Hearing them sing, he joined their march, sang for them, and donated money to their cause. He saw in their struggle against exploitation a parallel to the struggle of his own people, which allowed him to frame the fight for Black liberation within a broader, internationalist context of class struggle. This realization—that the oppression of a Welsh miner and a Black sharecropper stemmed from the same global system of capitalist exploitation—was a revelation that could only have occurred outside the rigid racial binary of the United States.

This burgeoning global conscience led him to the anti-fascist cause. As fascism rose in Europe, Robeson became one of its most outspoken artistic opponents. He was a fervent supporter of the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War, raising funds and, in a courageous 1938 visit, traveling to the front lines to sing for the international brigades fighting against Franco. It was at a 1937 rally for Spanish relief at London’s Royal Albert Hall that he made his definitive statement on the fusion of his art and politics: “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative”. This declaration crystallized the transformation that had taken place in London: Paul Robeson was no longer just an artist; he was an artist as revolutionary.

PART 3: The Soviet Question and the Rise of a Global Conscience (1934-1949)

Paul Robeson’s relationship with the Soviet Union is perhaps the most complex and controversial aspect of his life. His profound admiration for the USSR was born from a direct and visceral comparison with the brutal realities of fascism in Europe and institutionalized racism in the United States. To Robeson, the Soviet Union, with its constitutional prohibition of racial discrimination, appeared as a beacon of hope and a powerful ally in the global struggle against white supremacy. This allegiance, however, placed him in a tragic paradox, as his public loyalty to the Soviet ideal persisted even as he gained private, horrifying knowledge of the reality of Stalinist terror. His steadfast refusal to publicly condemn the USSR, a decision rooted in a complex geopolitical calculus, would ultimately provide the justification for his political persecution and erasure in America.

“I Walk in Full Human Dignity”: The Soviet Ideal

Robeson’s first visit to the Soviet Union in December 1934 was a pivotal, life-altering experience. The journey itself framed his perception. He and Essie traveled via Berlin, where they were accosted and threatened by Nazi stormtroopers, a harrowing encounter with the violent face of fascism. The contrast upon arriving in Moscow could not have been more stark. He was welcomed with an effusive warmth and respect that he had never experienced as a Black man in his own country. He was celebrated by leading artists like the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein and was struck by the everyday interactions with Russian citizens who approached him with open friendliness.

It was this experience that prompted his most famous declaration about the country: “Here, I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life. I walk in full human dignity”. This statement must be understood not as a naive endorsement of every aspect of Soviet life, but as a profound expression of relief from the crushing weight of American racism. In the USSR, he could eat in any restaurant and walk through the front door of any hotel—simple acts that were denied to him in much of the United States. For Robeson, the Soviet Union’s most compelling feature was its official, constitutional stance against racism. Article 123 of the 1936 Soviet Constitution, which made racial discrimination a crime, stood in dramatic opposition to the legally codified segregation of Jim Crow America. This legal and social affirmation of his humanity was so powerful that he and Essie later enrolled their son, Paul Jr., in a Moscow school for two years, seeking to shield him from the racism they knew he would face in the United States.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Robeson became a consistent and vocal champion of the Soviet Union, viewing it as a critical bulwark against fascism and a model for the decolonizing world. He publicly defended Soviet foreign policy, including the controversial 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which he argued was a strategic necessity forced upon Stalin by the refusal of Britain and France to form a genuine anti-fascist alliance. His pro-Soviet stance was a calculated geopolitical choice. In a world defined by American white supremacy and European fascism, he saw the USSR as the only major power ideologically committed to racial equality and willing to support anti-colonial movements in Africa and Asia.

The Paradox of Stalinism: A Tragic Loyalty

Robeson’s unwavering public support for the Soviet Union became increasingly problematic as the full scope of Stalin’s tyranny emerged. He remained silent about the regime’s most horrific atrocities, including the forced collectivization and the Great Famine (Holodomor) that killed millions in Ukraine, and the vast network of labor camps, or gulags. This silence has been the subject of intense debate among his biographers and critics. It was not, however, born of ignorance, but of a difficult political conviction. Robeson, along with his son and closest confidants, consistently argued that any public criticism of the USSR from a figure of his international stature would be seized upon by anti-Soviet forces in the West. He believed such criticism would provide ammunition to American imperialists and racists, undermining the global anti-colonial struggle and potentially fueling a preemptive war against the world’s only socialist superpower.

The agonizing nature of this paradox was made brutally clear during his visit to Moscow in June 1949. Alarmed by the disappearance of his Jewish friends in the Soviet artistic community, Robeson insisted on meeting with the celebrated Yiddish poet Itzik Feffer. The meeting was arranged by the state police, who brought Feffer directly from a prison cell to Robeson’s bugged hotel room. During their conversation, Feffer, looking terrified, communicated through frantic hand gestures that the great actor and leader of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Solomon Mikhoels, had been murdered by the state in 1948, and that he, Feffer, would soon be executed as well (he was shot in 1952).

Robeson was left with direct, undeniable proof of the murderous, anti-Semitic nature of Stalin’s postwar purges. He responded not with public denunciation, which he felt would endanger Feffer further and serve his political enemies, but with a courageous act of artistic protest. At his sold-out concert in Tchaikovsky Hall a few days later, which was broadcast across the Soviet Union, Robeson paid a deliberate tribute to his condemned friends. He spoke warmly of his friendship with Mikhoels and Feffer, and then, for an encore, he sang the partisan song from the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, “Zog Nit Keynmol” (“Never Say That You Have Reached the Final Road”). He first recited the lyrics in Russian so the entire audience would understand its message of defiance, and then sang it with deep emotion in its original Yiddish. It was a stunning and risky public gesture of solidarity with the victims of Stalin’s terror. Yet, upon his return to the United States, when questioned by the press, he denied any knowledge of Jewish persecution in the USSR. He had made a tragic choice: to compartmentalize his private knowledge and public stance, sacrificing the specific truth of Soviet atrocities for what he saw as the greater imperative of the global fight against American racism and imperialism.

The Paris Peace Congress and the Point of No Return (1949)

The event that irrevocably sealed Robeson’s fate in the United States was his speech at the World Peace Congress in Paris in April 1949. In an impassioned, off-the-cuff address, he spoke of the common struggle of workers and Black people against oppression. According to French transcripts and eyewitness accounts, he stated that it was unthinkable that Black Americans, who suffered such oppression at home, would want to participate in a war against the Soviet Union, a nation that had raised its minority peoples to “full human dignity”.

Before he had even finished speaking, a distorted version of his remarks was dispatched to the United States by the Associated Press. The AP dispatch, whose original source remains unknown, quoted him as saying that American Negroes would not fight for the United States against the Soviet Union. The distinction was critical. What was likely a statement of sentiment and moral opposition was reported as a declaration of disloyalty and potential treason.

The backlash in America was immediate and overwhelming. He was branded a traitor in newspaper editorials and denounced by politicians across the political spectrum. The speech became the primary justification for the government’s subsequent actions against him. The controversy culminated in the infamous Peekskill Riots in August and September of 1949. Two outdoor concerts he was scheduled to give in Peekskill, New York, were met with organized mob violence from local veterans’ groups and other anti-communist agitators. Concertgoers were brutally attacked with rocks and baseball bats while local and state police stood by or, in some cases, joined in the violence. Robeson was hanged in effigy, and a cross was burned on a nearby hill. The Paris speech and the violence at Peekskill marked the point of no return, launching the final, most intense phase of the campaign to silence Paul Robeson.

PART 4 : The Trial of Paul Robeson (1950-1958)

The decade following the Peekskill Riots was defined by a systematic and relentless campaign by the United States government, in concert with corporate and media entities, to destroy Paul Robeson’s career, cripple him financially, and erase his voice from the public sphere. This period of intense persecution culminated in his 1956 appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee, a confrontation he masterfully transformed from an interrogation of his loyalty into a powerful indictment of American racism and hypocrisy. His testimony stands as one of the most defiant and articulate acts of resistance of the McCarthy era.

The Blacklist and the Silencing

The campaign against Robeson was a prototype of modern political “cancellation,” a coordinated effort to make him a non-person. The mechanisms of persecution were both official and informal. Following his Paris speech, concert halls across the country cancelled his bookings under pressure from anti-communist groups. In 1947, Peoria, Illinois, became the first American city to officially ban him from performing. Recording companies refused to distribute his music, and his films were pulled from circulation. He was blacklisted by the burgeoning television industry, and NBC cancelled a scheduled appearance on Eleanor Roosevelt’s television show. The Council on African Affairs, which he chaired, was placed on the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations, further branding him an enemy of the state.

This blacklisting was designed to be economically devastating. His annual income, once over $150,000 (the equivalent of millions today), plummeted to less than $3,000 a year as his ability to earn a livelihood in his own country was systematically dismantled. While his previous investments and royalties kept him from destitution, the economic assault was severe and deliberate.

The cornerstone of this campaign was the revocation of his U.S. passport in August 1950. The State Department declared that his travel abroad would be “contrary to the best interests of the United States,” effectively making him a prisoner in his own country. This act was particularly crippling, as it severed his connection to the international audiences where he remained immensely popular and cut off his primary remaining source of income. For eight years, he fought a protracted legal battle to regain his right to travel. He filed lawsuits, faced endless delays, and refused to sign an affidavit swearing he was not a member of the Communist Party, arguing that such an oath was an unconstitutional violation of his rights of belief and association. The ordeal finally ended in 1958, when the Supreme Court ruled in

Kent v. Dulles—a case involving other activists—that the State Department could not deny passports based on a citizen’s political beliefs. The ruling set a precedent that restored Robeson’s freedom to travel.

Even while confined, Robeson refused to be silenced. He found creative ways to circumvent the travel ban, most famously in 1952 and 1953, when he held concerts at the Peace Arch Park on the border between Washington state and British Columbia, singing to tens of thousands of people on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border. In 1957, he made history by using a transatlantic telephone cable to perform a live concert for an audience of Welsh miners in Wales and another in London, his powerful voice bridging the ocean that his government forbade him from crossing.

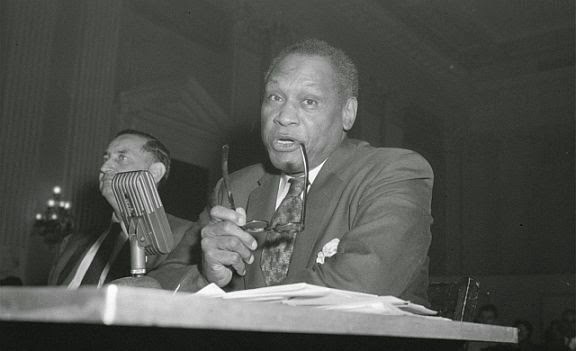

Testimony Before the House Un-American Activities Committee (1956)

On June 12, 1956, Robeson was subpoenaed to appear before HUAC in Washington, D.C. The hearing’s official purpose was to investigate the “unauthorized use of United States passports,” but its true intent was to publicly humiliate and discredit one of the committee’s most formidable critics. Robeson, however, refused to be the victim. A trained lawyer and a master orator, he turned the hearing into a powerful piece of political theater, employing a rhetorical strategy of defiant counter-attack.

He consistently invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination when asked about his membership in the Communist Party. However, he did so not as a shield, but as a sword. He challenged the committee’s premise, stating that the Fifth Amendment has “nothing to do with criminality” and refusing to dignify their questions.

Instead of answering directly, he would lecture the congressmen, asking them to define what they meant by the Communist Party: “Do you mean a party of people who have sacrificed for my people, and for all Americans and workers, that they can live in dignity? Do you mean that party?”.

This rhetorical jujitsu—seizing the moral high ground and putting the committee’s own motives on trial—defined the entire proceeding. He successfully reframed the hearing from a trial of his loyalty to a trial of America’s racial hypocrisy. His most memorable exchanges have become legendary moments in the history of American dissent:

When Committee member Gordon Scherer asked him why, if he admired the Soviet Union so much, he did not stay there, Robeson delivered his most famous retort:

“Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?”

This statement brilliantly transformed the question of his loyalty to a foreign power into an assertion of his inalienable birthright as an American, a right paid for by the suffering of his ancestors.

When pressed to condemn Stalin and the Soviet gulags, he again turned the question back on the committee, indicting America’s own history of racial terror:

“Whatever has happened to Stalin, gentlemen, is a question for the Soviet Union, and I would not argue with a representative of the people who, in building America, wasted sixty to a hundred million lives of my people, black people drawn from Africa on the plantations… don’t ask me about anybody, please.”

He explicitly stated what he believed to be the true reason for the hearing, articulating the State Department’s own rationale for revoking his passport:

“I am not being tried for whether I am a Communist, I am being tried for fighting for the rights of my people, who are still second-class citizens in this United States of America… You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of his people…”

At the hearing’s conclusion, Robeson lambasted the committee members directly, declaring, “You are the non-patriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves”. He had prepared a formal statement for the committee, which he was forbidden to read. In it, he detailed his belief that he was being denied his rights because of his anti-colonial advocacy and his outspokenness against American racism. Though silenced in the hearing room, his defiant performance and powerful words resonated across the country, particularly in the Black press, which hailed him as a hero who had stood up to his persecutors and spoken truth to power. He had lost the battle for his passport but had won a profound moral and rhetorical victory.

PART 5: Legacy, Erasure, and Rediscovery

The relentless persecution Paul Robeson endured left indelible scars on his health, his career, and his place in American history. The final decades of his life were marked by a tragic decline and a forced withdrawal from the public stage he had once commanded. His erasure from the nation’s popular memory was a testament to the effectiveness of the Cold War campaign against him. Yet, his monumental legacy could not be permanently suppressed. In the years since his death, a slow but steady re-evaluation has restored him to his rightful place as a pioneering artist, a courageous activist, and one of the most significant and challenging figures of the 20th century.

5.1 The Toll of the Struggle

The eight-year struggle to regain his passport and the constant surveillance and harassment took a severe toll on Robeson’s physical and mental health. After his passport was finally restored in 1958, he embarked on a triumphant world tour, performing at sold-out venues like Carnegie Hall and London’s Royal Albert Hall and reprising his role as Othello at Stratford-upon-Avon. However, the years of pressure had exhausted him. During a trip to Moscow in 1961, he experienced a severe bout of depression and paranoia and reportedly attempted suicide. He was hospitalized in both Moscow and London, where he was subjected to dozens of electroshock treatments.

His health was irreparably broken. Realizing he could no longer perform to his own exacting standards, he retired from public life in the early 1960s. Following the death of his wife, Essie, from cancer in 1965, he moved into the home of his sister Marian in West Philadelphia, where he lived in self-imposed seclusion until his death from a stroke on January 23, 1976, at the age of 77.

5.2 An Un-American Hero: The Erasure from History

For decades, Paul Robeson was effectively erased from mainstream American history. This was not a passive forgetting but the result of a deliberate and successful campaign to render him a non-person. His records were not sold, his films were not shown, and his name was omitted from textbooks that should have celebrated him as a pioneering athlete, actor, and singer.

This erasure was abetted by the strategic decisions of the mainstream Civil Rights Movement. During the height of the Cold War, leaders of organizations like the NAACP made a calculated choice to distance themselves from Robeson, whose unapologetic pro-Soviet stance and radical politics were seen as a liability in their fight for legitimacy and federal support. Figures like Jackie Robinson were promoted as a more palatable, anti-communist model of Black achievement. Robinson was called before HUAC in 1949 to testify that Robeson’s controversial Paris statements did not represent the views of Black Americans. The movement’s need to frame its struggle as a fulfillment of American democratic ideals, rather than a revolutionary critique of them, left no room for a figure as uncompromising as Robeson. His marginalization was thus a consequence not only of the actions of his enemies but also of the strategic imperatives of his would-be allies.

5.3 The Re-evaluation of a Titan

Even before his death, the process of re-evaluating Robeson’s legacy had begun. In his later years, Jackie Robinson expressed profound regret for his HUAC testimony, writing in his autobiography that he had “grown wiser” and had “increased respect for Paul Robeson who, over the span of twenty years, sacrificed himself, his career, and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people”. A new generation of Black artists, including Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte, began to publicly credit Robeson with having paved the way for their own careers.

After his death, the rehabilitation of his legacy accelerated. Posthumous awards and honors sought to rectify the decades of neglect. He received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1998 and an Academy Award in 1980. In 1995, more than 75 years after he last played for Rutgers, he was finally inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. His alma mater, Rutgers University, which had once distanced itself from him, now proudly claims him as one of its most distinguished alumni, having named a cultural center, a library, and a campus plaza in his honor.

Today, Paul Robeson’s legacy is being rediscovered by new generations who see in his life a powerful story of courage, conviction, and resistance. He is remembered as a visionary who understood the interconnectedness of global struggles for freedom and who used his art as a weapon for justice. However, this rehabilitation often involves a selective embrace of his accomplishments—celebrating the singer, actor, and athlete while sanitizing the radical socialist and unapologetic defender of the Soviet Union. A true and complete understanding of Paul Robeson requires grappling with the totality of his life: the magnificent talent and the controversial politics, the unwavering commitment to his people and the tragic paradoxes of his alliances. His life challenges us to confront the uncomfortable truth that the same American society that produced a man of such immense genius also tried to destroy him for daring to demand that it live up to its own ideals. His story remains not just a record of a great life, but a enduring cautionary tale about the profound cost of dissent in the United States.

Appendix A

Table 1: Chronological Context: The Life of Paul Robeson in a Century OF CHANGE

1898

Born in Princeton, NJ, son of a former slave.

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) establishes “separate but equal.”

1915-1919

Attends Rutgers; named All-American, graduates valedictorian.

World War I (1914-1918);

Red Summer of 1919.

1920-1923

Attends Columbia Law;

plays in the early NFL.

Harlem Renaissance begins to flourish

1924-1925

Stars in Emperor Jones &

All God’s Chillun Got Wings.

Harlem Renaissance begins to flourish

1928-1930

Moves to London; stars in Show Boat and Othello.

The Great Depression begins (1929).

1934

First visit to the Soviet Union after encounter with Nazis in Berlin.

Hitler becomes Führer of Germany.

1943

Stars in record-breaking

Broadway run of Othello.

World War II; Detroit Race

Riot.

1946

Confronts President Truman over federal anti-lynching law.

The Cold War begins.

1949

Paris Peace Congressspeech; Peekskill Riots.

Soviet Union tests its first atomic bomb; NATO is formed.

1950

U.S. State Department revokes his passport.

Senator Joseph McCarthy begins his anti-communist crusade.

1956

Testifies defiantly before HUAC.

Montgomery Bus Boycott; Hungarian Revolution.

1958

Passport reinstated after Supreme Court ruling (Kent v. Dulles).

Height of the Cold War.

1961-1965

Health deteriorates; retires from public life.

Peak of the Civil Rights Movement; Voting Rights Act of 1965.

1976

Dies in Philadelphia at age 77.

Post-Watergate era; end of Vietnam War.

1995

Inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Post-Cold War re-evaluation of historical figures.

Wikipedia/Reference Sources

Paul Robeson – Wikipedia

Paul Robeson congressional hearings – Wikipedia

Political views of Paul Robeson – Wikipedia

Paul Robeson filmography – Wikipedia

Body and Soul (1925 film) – Wikipedia

Itzik Feffer – Wikipedia The Proud Valley – Wikipedia Song of Freedom – Wikipedia

Tales of Manhattan – Wikipedia Show Boat (1936 film) – Wikipedia Ol’ Man River – Wikipedia

Educational/Academic Institutions

Paul Robeson | Britannica

Activist on the Global Stage: Paul Robeson 1923 | Columbia Law School

About Paul Robeson | Paul Robeson at Rutgers

Paul Robeson Football Star | Rutgers University

Paul Robeson’s Journey to Activism | Rutgers University Groundbreaking Honors Paul Robeson’s Legacy | Rutgers University

West Philadelphia Collaborative History – Paul Robeson, Part II

West Philadelphia Collaborative History – Paul Robeson, Part III

West Philadelphia Collaborative History – Paul Robeson, Part IV

Proud Valley · Paul Robeson and Wales · Swansea University

Legacy and Black Lives Matter · Paul Robeson and Wales · Swansea University

Museums/Archives

The Many Faces of Paul Robeson | National Archives

Paul Robeson House & Museum

Paul Robeson Biography | American Masters | PBS

The Emperor Jones (1933) | The Criterion Collection

Body and Soul (1925) | The Criterion Collection

The Proud Valley (1940) | The Criterion Collection

Body and Soul | MoMA

Paul Robeson | Blue Plaques | English Heritage

Paul Robeson: the singer and activist | BFI

Historical/Educational Resources

June 12, 1956: Paul Robeson Testifies Before HUAC – Zinn Education Project

Oct. 14, 1916: Paul Robeson Excluded from Rutgers Football Team – Zinn Education Project“

You Are the Un-Americans”: Paul Robeson Appears Before HUAC

Paul Robeson’s Appearance Before HUAC (1956) | The American Yawp Reader

News/Media Sources

Singer, actor, athlete, activist Paul Robeson dies | HISTORY

What Paul Robeson Said | Smithsonian Magazine

How Britain Made Paul Robeson a Socialist | Tribune Magazine

Paul Robeson Spent His Life Fighting Against America’s Extreme Right | Jacobin

The Price of Self-Delusion – The American Interest

Paul Robeson and Russia | Classical Music

Biography/Registry Sites

Paul Robeson, Athlete, Actor, Singer, and Activist – African American Registry

Paul Robeson – Wife, Movies & Death | Biography.com

PAUL ROBESON, a brief biography

Paul Robeson’s Sports Career

Film/Entertainment Databases

Paul Robeson | Actor, Soundtrack | IMDb

Paul Robeson Movies List | Rotten Tomatoes

Body and Soul (1925) – Turner Classic Movies

Body and Soul (1925) | IMDb

Show Boat (1936) | IMDb

Song of Freedom (1936) | IMDb

Tales of Manhattan (1942) | IMDb

Body and Soul (1925) | Rotten Tomatoes

Sports References

Paul Robeson Stats | Pro-Football-Reference.com

Paul Robeson (1995) – Hall of Fame – National Football Foundation

Paul Robeson Career Stats | NFL.com

Academic/Political Analysis

Paul Robeson: The Left’s Tragic Hero – Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung

Paul Robeson’s Tragic Love of Russia | Past in Present

Paul Robeson in the Soviet Union – Picturing Black History

Grover Furr — Paul Robeson’s Meeting with Itzik Feffer | In Defense of Communism

Paul Robeson, HUAC, and institutional narrative authority | Quarterly Journal of Speech

Performing Dissent: Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson before HUAC

Paul Robeson and the End of His “Movie” Career – Cinémas

Other Resources

Resistance and Paul Robeson | Revealing Histories

Body and Soul | Silent Film

BFI Screenonline: Song of Freedom (1936)

BFI Screenonline: The Proud Valley (1940)

Wales on Film: The Proud Valley (1940) | Wales Arts Review

Paul Robeson Appears Before HUAC, 1956 – CWIS Collection